Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Reclamation, rejection, or creation: what does agency mean?

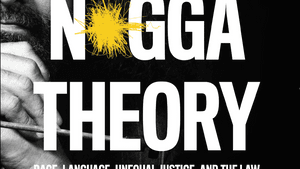

‘N*gga Theory: Race, Language, Unequal Justice, and the Law,’ by Jody Armour

N*gga. It’s the last thing you’d probably expect to read on the cover of a book published in 2020, a year filled with the promise of social justice and Black lives mattering. It’s shocking, perhaps even upsetting, but surely compelling when coupled with the word theory. Jody Armour’s N*gga Theory: Race, Language, Unequal Justice, and The Law is a call to action, a book centered on what the author considers to be a theory of justice, and perhaps it’s right on time.

A moral distinction?

A criminal law professor, and son of a formerly incarcerated Black man and white red-headed mother, Armour demands that you call him a N*gga. For Armour, this country makes a moral distinction between Negroes and n*ggas, with the former being law-abiding and the latter law-breaking, a distinction which he aims to remove. His theory is based on the premise of solidarity, and the removal of respectability politics, or the idea that racial oppression can end if Black people do things to gain the respect of whites, including distancing themselves from those who have committed crimes. He contends that this divides Black people into two groups: Negroes and n*ggas.

This leads the Black reader to wonder two things: is it necessary or beneficial to be in solidarity and community with Black people who’ve committed crimes, including violent ones? And does referring to each other as n*gga necessitate social justice?

Armour asserts that the answer is yes. He goes beyond Michelle Alexander’s affirmative, which advocates for Black people who’ve committed nonviolent crimes, as outlined in her groundbreaking 2010 text The New Jim Crow. Armour argues that even those who’ve committed violent crimes such as murder and rape, the “n*ggas,” the so-called wicked, should be united with the “worthy” Black people.

A strong case

As the basis of N*gga Theory, this argument is just as controversial as the name of the theory itself. But Armour doesn’t shy away. In fact, he welcomes and even empathizes with the criticism while making the case that in order to address the deeply rooted racism that dominates this country, Black people must be willing to align themselves with their most marginalized community members.

Utilizing data and proactively addressing opposing views, as any good lawyer would, he makes a strong case about race, unequal justice, and the law. His theory is a call to end respectability politics, which are not only a product of white supremacy, but create division between Black people. Armour wants to recognize that the majority of incarcerated Black people are in fact doing time for violent crimes rather than nonviolent ones, and he advocates reducing incarceration levels with restorative practices for those who’ve committed violent crimes. He also calls out the racist system that automatically assumes criminal intent when handling cases involving Black people, creating the impoverished and unjust circumstances that ultimately lead to violence and still disproportionately imprison Black people. Armour insists Black people don’t owe this unjust system anything, even after committing a crime.

Language and agency

But the author’s case on language falls short. Bringing about the social changes he advocates for and keeping racism at the center of the conversation don’t require using the n-word. Even with all of his evidence, Armour does not effectively demonstrate how using this terminology, instead of something else, is actually beneficial in bringing about political action and social justice. In fact, he illustrates that it’s the social changes themselves, not being “called a n*gga,” that can greatly and positively impact the Black community. And it would be easy to state that the social action resulting from the theory is more important than its name. Perhaps it is, but Armour demonstrates successfully just how vital language and words really are.

The text is tremendously invested in the idea of using the n-word. Explaining the use of a different term or expanding on the implementation of this social theory rather than seeking to justify n*gga would’ve been a better use of the pages. Armour is preoccupied with the agency to reclaim something negative, but agency can also take the form of rejection and creation.

New structures needed

Why not create something that is truly from the Black perspective? Something that rejects a major symbol of the very system he claims to be fighting? Why not reclaim something positive from an African ancestral past that has never been negative, something with the potential not only to unite but to liberate? In reclaiming more culturally relevant terms or creating new positive ones, Black people can also reclaim and create more appropriate measures of handling crime amongst their people. Like the rejection of the term n*gga, they can build structures that reject the Eurocentric models of punishment and morality that plague them.

Armour’s call to action is profound, necessary, and right on time, but calling “Negroes” n*ggas won’t solve the problem of racism in the criminal justice and legal systems. It’ll only lead to more n*ggas.

Image description: The cover of the book N*gga Theory, by Jody Armour. On the left, there’s a close-up photo of serious man’s face, resting on folded hands. The title is in white block letters, with an emphatic yellow scribble in place of the asterisk in “N*gga.”

What, When, Where

N*gga Theory: Race, Language, Unequal Justice, and the Law. By Jody Armour, with a foreword by Larry Krasner. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Review of Books, August 18, 2020. 288 pages, paperback, $18 at Bookshop.com

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Lindsay Gary

Lindsay Gary