Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

William Penn and prostitutes: All the news that's unfit to print

'Wicked Philadelphia: Sin in the City of Brotherly Love,' by Thomas H. Keels

Wicked Philadelphia, Thomas H. Keels’s 2010 study, subtitled “Sin in the City of Brotherly Love,” is a volume that will definitely appeal to trivia geeks. In its three-page opening note on geography alone there are enough obscure facts to keep an army of hipsters happy for several rounds of microbrewed beer: Race Street was once called Sassafras; in 1800 Northern Liberties was the sixth largest city in the United States, and so forth.

Keels’s intention, however, is not to entertain those taken with the ultimately insignificant. His book, one of his several about his adopted city, examines the longstanding tension between the intentions of Philadelphia’s high-minded founders and later reformers, and the effects of jamming many people, some not so “brotherly,” into a relatively small area. As Governor William Markham observed in 1697, “As this place hath growne more popular and the people more increased, Looseness and Vice Hath also Crept in.”

The drift from William Penn’s notion of a New Jerusalem began soon after his death, when his sons began cheating the Lenni-Lenape out of treaty-guaranteed land. Among other questionable methods, the Penns employed professional athletes to turn the Native American practice of marking land bought by a measured walk into a 36-hour marathon.

Keels also sees the “legalisms” and veneer of “civilization” used by the Penns to fleece the Lenni-Lenape reflected throughout our local history. His examples include Ira Einhorn, who preached love and peace while his girlfriend rotted in another room in his apartment, and John G. Bennett, Jr., who stole millions from nonprofits, charities, and schools, and planned to use “possession by religious fervor” as his legal defense.

That old, upper-crust dirt we’ve forgotten

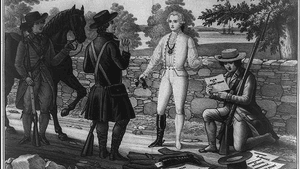

Keels starts with a story of the late 19th-century upper crust rubbing elbows with a long-dead colonial enemy. Brit John Andre organized the ultra-lavish Mischianza ball in 1778. In 1896, descendants of the Chew family recreated that event, dressing as Andre and his reputed lover, Peggy Chew (and yes, there are photos).

Andre was eventually hanged for spying after serving as a part-time soldier and social secretary to General Howe, who ran the British occupation of Philadelphia and had a grand old time, often with the local wealthy, while Washington’s troops froze in Valley Forge. But by 1896, Keels writes, British decadence in Philadelphia was forgotten or ignored, and “the traitors of 1778 had been transformed into the transatlantic trendsetters of 1896.”

It’s an interesting story to start with, and may simplify a bit, by that use of “traitors,” the difficult position of some wealthy Philadelphians who attended a party in occupied territory 118 years earlier. Then again, those who win the war make the history, and historians very often side with the winners and decide who are called traitors.

And the dirt of the less well-dressed

What about the juicy stuff, though? There are revelations that may strike some as unexpected. Local prostitution, for example, literally began in caves along the Delaware River (they were eventually demolished on William Penn’s watch), but the so-called oldest profession flourished in the 18th century among all classes. Nineteenth century reforms changed that, geographically isolating brothels and “strollers,” but that reformation backfired, creating a flourishing industry that still exists.

Prostitution flourished here even in the mid-1800s to the point that there was by 1849 a published guide to brothels. Keels also asserts (without specifics) that some prostitutes at that time were visited within a 24-hour period by married couples: by the husband for services and by the wife for a lecture on morality. The two prominent prostitution reform societies at work in the 19th century here tried hard (one maybe too hard), but for every woman they saved from a life of sin, a hundred were ready to take their place, in Keels's estimate, because of "desertion, entrapment, pregnancy, widowhood, divorce, rape, or simple poverty."

Keels also recalls some of the famous individual scandals of those times and after the mid-19th century. If you don’t know about the sensational Heberton-Mercer case, or the Storey Cotton Ponzi scheme, or the Dot King murder, this is a neat little well-written book for you. A warning, though: the chapter on one of our prominent medical schools’ complicity in body snatching is not for the physically or ethically faint of heart.

What, When, Where

Wicked Philadelphia: Sin in the City of Brotherly Love. By Thomas H. Keels. The History Press, 2010. 124 pages, paperback; $18.48, available at Amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Rick Soisson

Rick Soisson