Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Scorned by critics, adored by the masses

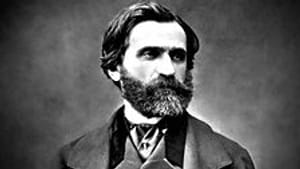

Verdi at 200 (Part 2): A private life in public

Second in a series of articles about Giuseppe Verdi.

In my previous article, we saw how Verdi’s early operas focused on stories about oppressed people, and his melodies became theme songs for the Italian independence movement. (Click here.) Some revisionist historians have questioned Verdi’s connection to the struggle, claiming that he abandoned the independence cause by 1850. But the Risorgimento was an uneven progression that stalled at the end of 1849, when Austrian troops recaptured Venice and restored the princes who had been expelled from central Italy. French forces subsequently occupied Rome, and the Risorgimento leaders Garibaldi and Mazzini fled into exile. In 1850 Garibaldi was a fugitive in New York City.

At that point the revolutionary phase was over. But a decade later a diplomatic aspect emerged, led by Count Camillo di Cavour of the House of Savoy, and in 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed in Turin by a parliament that included elected representatives from most parts of Italy. Not until 1866 was Venice freed from Austrian rule, and it was 1870 before Rome was severed from Papal control.

Thus after 1849 Verdi had no opportunity to converge with leaders of the independence cause. What’s more, Verdi was a private man who rarely reached out to others. “Please leave me at home at peace,” he wrote to a colleague. Verdi was preoccupied with his common-law relationship with Giuseppina Strepponi, which estranged him from his religiously observant parents. “For my greater peace of mind,” he explained in one letter, “I intend to be separated from my father in my residence and in my business.”

In another letter— to the father of his late wife— Verdi asked rhetorically, “What harm is there if I live in isolation? If I choose not to pay calls on titled people?... In my house there lives a lady, free, independent, a lover like myself of solitude, like myself possessing a fortune that shelters her from all need. Neither I nor she owes anyone an account of our actions.”

Adulterous wife

Amid all this personal angst, Verdi concentrated on his craft. Between 1849 (when he was 36) and 1871 he composed a dozen remarkable operas, including some of his greatest. In many of these, Verdi’s personal life was a subject. Luisa Miller, for example, is an intimate drama of domestic life that presaged La Traviata in its focus on bourgeois hypocrisy.

Next came Stiffelio, a philosophical drama of hypocrisy concerning a Protestant minister with an adulterous wife. As his private agonies clashed with his public responsibilities, this brave cleric publicly forgave her from his pulpit. Verdi wanted Stiffelio performed in contemporary dress to indicate its immediate relevance, but censors eliminated the church scene and the contemporary setting as well. When later productions made even greater cuts, Verdi angrily withdrew Stiffelio from circulation but re-used parts of it for his Aroldo, set in 13th-Century Anglo-Saxon England. The discovery of the composer's original manuscript in 1992 led to a Metropolitan Opera restoration, which should be worth seeing when it next appears.

‘Nauseating spectacle’

Four months after Stiffelio, Verdi premiered his Rigoletto, the grizzly story about the licentious Duke of Mantua, his court jester Rigoletto, and Rigoletto's sheltered daughter Gilda. It is a compact opera, dark in tone, touching on abduction, rape and murder. The innovative Act IV quartet calls for four characters to sing dissimilar types of melodies in different rhythms. A vivid storm scene includes lightning flashes by flutes and the moan of the wind by the humming of choristers.

In what we can see as an expression of Verdi’s personal feelings, the hump-backed title character is scorned by court society and becomes a subject of sympathy. We root for him despite his participation in evil. I, for one, find myself caring even more about him than about his innocent daughter.

The Venice Gazzetta commented on “the oddness of the subject and novelty in the music... The instrumentation was stupendous, admirable; the orchestra speaks to you, cries out to you, it instills passion in you. [But] we cannot in good conscience praise such taste.” Added the Lombardo Veneto, “It is an unbroken fabric of instrumentation which either speaks softly to your soul, or awakens you to pity, or horrifies you.” L’Italia Musicale praised Verdi’s turning-away from “grandiose ensembles, big arias, noisy finales. [But it leaves us] empty and disgusted at such a horrendous and nauseating spectacle.”

(The most recent opera by Wagner, who was Verdi’s age, was the grandiose, big-ensemble Lohengrin.)

Gypsy heroine

Il Trovatore followed just a few months later, in January 1853, and again featured a woman despised by society. This is the gypsy Azucena, assigned to a mezzo or contralto to denote the dark way she was viewed by the world. Verdi wanted to name the opera after her, rather than the troubadour Manrico. Azucena, he wrote, was “the principal role; finer and more dramatic and more original than the other.” Leonora, the soprano, is characterized by a soaring “aspiring” quality, whereas Azucena's melodies are direct and blunt. Verdi obviously felt more of a personal connection to his gypsy mezzo than to his romantic soprano.

In Paris in 1852 Verdi and Strepponi attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady of the Camellias) and he immediately decided to turn it into an opera. Verdi considered naming the piece for its leading character, Violetta, before settling on La Traviata (The Fallen Woman)”— “a subject for our own age," he remarked in a letter. Verdi wanted Traviata set in the present day, with a “realistic” production. Subtlety was never Verdi’s strong suit.

Better than Broadway

Police censors forced the setting to be changed to “circa 1700,” yet the opera was denounced anyway for excusing immorality. Despite its indecent story and tragic ending, audiences walked out of the theater humming Libiamo, Ah fors' è lui, Sempre libera, Dei miei bollenti spiriti, Di provenza il mar and Addio del passato. That was six hit songs in one show, far more than any Broadway musical of our 21st Century.

And that’s where Verdi stood at age 40, in the midst of his most productive years— his partner shunned, his choices criticized, while his operas were the most performed in the world. I suspect the Italian masses were drawn to Verdi’s liberated lifestyle and independent political thinking as much as his music, even though the ruling class disapproved. Or maybe because the ruling class disapproved.

In my next article, I’ll discuss Verdi’s respect for words, and his passion for adapting exceptional literature.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Steve Cohen

Steve Cohen