Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

From ‘Citizen Kane’ to 'Goodfellas’ with Donald Trump

Trump, through a Hollywood lens

How did Donald Trump get where he got? What happens now? How will it end?

Last week I proposed a psychological explanation for our new president’s behavior. But there’s a less painful and more entertaining way to approach the Trump phenomenon. You could do worse than watch and reflect upon a few classic Hollywood films. For instance:

How we got here

Being There (1980; Hal Ashby directed, from Jerzy Kosiński’s novel). A simple-minded gardener (Peter Sellers), having been locked in a private home for 50 years, is set loose on the streets of Washington, where his babblings about roots and branches are taken for wisdom, his long silences are perceived as cool detachment, and consequently he winds up as a presidential adviser. Trump is no Chauncey, of course. But his political rise, like Chauncey’s, benefitted from other people’s eagerness to project their own hopes and dreams onto the protagonist’s drivel.

High Noon (1952; Fred Zinnemann directed). Once upon a time, in a small frontier town, the citizens rallied behind the local US Marshal, Will Kane (Gary Cooper), when he arrested and jailed a vicious killer. Now, five years later, the killer has inexplicably been released from prison and will soon return with his gang, bent on revenge -- and this time, when Kane tries to organize a posse, he encounters only excuses, petty resentments, and outright rejection. If you’ve wondered how millions of Americans who voted for Obama in 2008 could vote for Trump in 2016, this Western classic is a good place to start.

The Manchurian Candidate (1962; John Frankenheimer directed, from Richard Condon’s novel). Russian agents plot to install a pliable president in the White House, a Joe McCarthy-like demagogue who is widely dismissed as a fool but prone to Russian influence. The Russians employ strategic brainwashing rather than computer hacking (the Internet hadn’t yet been invented), but otherwise the plot sounds familiar, yes? One key difference: In the movie, the scheme is foiled at the last minute. Ah, the good old days.

Citizen Kane (1941; Orson Welles directed). Narcissistic media mogul Charles Foster Kane (Welles) creates his own reality in his newspapers and radio station (among other things, he promotes himself for governor and touts his marginally talented wife as an operatic diva). In lieu of love and friendship, Kane acquires material objects and gaudy mansions (Kane’s Xanadu in Florida could be a stand-in for Trump’s Mar-a-Lago). “I don’t suppose anybody ever had so many opinions,” remarks Kane’s oldest friend, Jedidiah Leland (Joseph Cotten). “But he never believed in anything except Charlie Kane. He never had a conviction except Charlie Kane in his life.” Trump, of course, lacks the introspection to see himself in Kane; in 1992 he identified Citizen Kane as his “all-time favorite movie,” an endorsement he repeated in his interview with Megyn Kelly last May. One key difference: Unlike Trump, Kane fails in his quest for public office.

A Face in the Crowd (1956; Elia Kazan directed). Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith), a manipulative homespun demagogue with no sense of his limitations, develops a huge nationwide following on the strength of “the courage of his ignorance.” Despite his lack of political credentials, he declares, “In a time of crisis, who else could rally the people like Lonesome Rhodes?" Lonesome self-destructs when he inadvertently voices his contempt for the common people into an open mike. Apparently, common people were savvier back then.

What happens now?

Bananas (1971; Woody Allen directed). In this farce about a populist revolution south of the border, a newly installed Fidel Castro-style dictator creates his own reality by (among other things) designating Swedish as the national language and proclaiming that all of his subjects under age 16 are now, by executive order, 16 years old. At least our 45th president hasn’t yet ventured that far into the wonderland of “alternative facts."

How will it end?

McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971; Robert Altman directed). In a forlorn frontier village, a fast-talking gambler (Warren Beatty) fancies himself the town’s leading citizen because his saloon-casino-bordello complex dominates the local landscape. In his self-absorption, McCabe fails to notice a Presbyterian church rising at the other end of town. At the climactic moment, the church catches fire— and the villagers rush to extinguish the flames, oblivious to McCabe’s personal life-and-death crisis. If High Noon (above) reflects the fickleness of the masses, McCabe and Mrs. Miller suggests that ordinary folks do come to their senses sooner or later.

Born Yesterday (1950; George Cukor directed, from the play by Garson Kanin). Harry Brock, a thuggish tycoon accustomed to buying political support for his nefarious business schemes (Broderick Crawford), descends upon Washington accompanied by his crooked lawyer and his girlfriend, a seemingly ditzy showgirl named Billie Dawn (Judy Holliday). Harry has signed over many of his assets to her in order to hide them from the IRS. Embarrassed by Billie’s ignorance and gauche behavior in polite society, Brock hires a tutor to polish her rough edges. The tutor, a journalist named Paul Verrall (William Holden), succeeds too well. In the process of introducing Billie to the White House, the Capitol, and the Lincoln Memorial, he endows her with such a reverence for American ideals and determination to think for herself that, in short order, she dumps Brock and runs off with Verrall. Makes you wonder what Melania, absent from the public eye since her husband's inauguration and presumably secured away in her gilded Trump Tower cage, is thinking right now.

Goodfellas (1990; Martin Scorsese directed). How does unchecked power plant the seeds of its own destruction? This mafia classic provides perhaps the best illustration. The wiseguys portrayed here seem unstoppable— impervious to police, federal agents, rival gangs, you name it. So what happens? In their overconfidence, they begin cheating, betraying, and killing each other. At the same time, they destroy themselves with drugs. Before you know it, their seemingly disciplined organization implodes. According to some White House leaks, similar infighting has already begun in Trumpworld. Did I mention that Goodfellas is based on a true story?

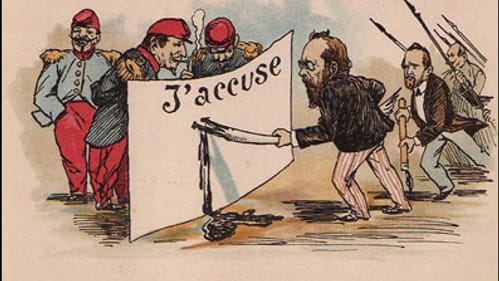

The Life of Émile Zola (1937; William Dieterle directed). In his middle age, celebrated French novelist Zola (Paul Muni), a pioneer of “naturalist” fiction, seemed content to coast on his well-deserved reputation as a national literary icon. Then, in 1894, along came the Dreyfus case, in which the French army’s general staff tried to conceal a traitor in its ranks by scapegoating an innocent Jewish officer. Zola, jolted out of his complacency, jumped into the controversy, leveraging his prestige to expose the Dreyfus frame-up in an open letter to the president of France. In the process, Zola upended his own secure life: He was convicted of criminal libel, briefly fled to England to avoid prison, and ultimately died of carbon monoxide poisoning that may not have been accidental. Today Zola is remembered more for his heroic defense of Dreyfus than for his novels.

In the coming months and years, many prominent and comfortable Americans may find themselves, like Zola, unexpectedly called upon to stand up for truth and justice at the risk of their status, their careers, or even their lives. In the process, also like Zola, they may discover strengths they didn’t realize they possessed. You or I, perhaps?

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg