Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Three new neo-noir films

When a war comes home:

Three stylish new neo-noir films

ROBERT ZALLER

It’s not my imagination, is it, but the less we see of real gore, the more addicted we seem to be to the cinematic kind. I haven’t seen a scratch on an American soldier this year except in Ken Burns’s The War, yet the numbers tell me more Americans have died in Iraq and Afghanistan this year than in any previous year since 9/11. Blood will out, though, even if only at the multiplex.

Ridley Scott and the Coen brothers, Ethan and Joel, are veteran bloodletters, so the wetwork in American Gangster and No Country for Old Men is little cause for surprise. Sidney Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, however, is far and away the darkest film of his career, and the near-simultaneous arrival of all three films at area screens suggests a neo-noir revival of sorts.

In a long-forgotten essay, I once traced the representation of violence in American film from the post-World War II era to the late ’70s. Needless to say, film violence has been alive and well since— indeed, so formulaic as to defeat all attempts at commentary. The difference now is that we are once again at war, but a war that, sanitized to the point of being virtually unreportable, has also proved all but unrepresentable. We must look elsewhere to see what is seeping through the carpet.

Bad father, model avenger

Only Before the Devil is more or less contemporary in its setting. Andy Hanson (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman), a Manhattan broker with an ED problem, a heroin habit and a kid’s grudge against his parents, conceives the perfect crime to foil the discovery of his embezzlements: He will rob his parents’ jewelry store. He enlists his younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) in the caper— all in the family— but when the latter subcontracts the work, everything goes wrong. Dad (Albert Finney) is left a widower, and gradually conceives a suspicion. Finney has been a bad father, as he confesses to Andy; but he proves a model avenger.

The film’s mayhem is actually limited, but it’s shocking enough when it comes. The real violence, however, lies coiled in the family relationship; and what comes out, Lumet suggests, is only a glimpse of what the heart contains within. In a key scene, Finney is taunted by an old colleague who tells him that the world is divided between those who can profit from its evil and those who are merely its victims. The Devil certainly does know when you’re dead.

Fargo South, with one difference

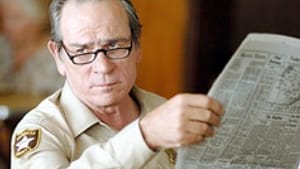

In No Country for Old Men, based on Cormac McCarthy's novel and set in the west Texas of 1980, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) discovers the carnage of a drug deal gone bad, but not before a local civilian, Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), arrives to make off with the swag. Llewelyn is a Vietnam vet and handy with a gun, but he is in over his head against the stone killer (Javier Bardem) who pursues him to retrieve it. Bardem’s Anton Chigurh is a self-styled angel of death who gives his prospective victims a coin-toss chance for life, but he’s so proficient at his trade that not even Woody Harrelson can stop him.

All of this, down to the psycho assassin, is familiar enough from the Coen brothers, and No Country could almost be titled Fargo South. The difference lies not in the bad guys, but in Sheriff Bell, the good one. In Fargo, violent crime takes a rural community by surprise, but Frances McDormand’s lady cop patiently tracks her villains down, knowing that Nordic persistence and attention to detail will get the job done. Sheriff Bell’s county, however, with its elegant desert vistas (superbly photographed by Roger Deakins), has turned into a shooting gallery, and no possibility of order remains.

Familial corruption, yet again

American Gangster is a reprise, too, in this case of the French Connection movies of the 1970s— there’s even an insider reference to Fernando Rey, of “Frog One” fame. As in No Country, drug wars provide the context; as in Before the Devil Knows, familial corruption is the driving theme. If No Country is visually stunning in its breadth, Ridley Scott’s Vietnam-era Harlem, phantasmagoric and raw, virtually implodes its space.

Denzel Washington has more on-screen physical presence than any actor of his generation, and his Frank Lucas, based on the real-life drug kingpin, is an Oscar-worthy performance. Russell Crowe, as the one honest cop on the force in two states, has the unenviable acting task of avoiding Al Pacino’s Serpico and Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle. Pitching himself somewhere in between, he does what he can with an overworked and underwritten role. (Carla Gugino is terrific as his suffering wife, though, and almost pulls enough character through for both of them.) But we’ve seen it before; so why again?

Seeds planted in Vietnam, and Iraq too

The why, both in Gangster and No Country, is a war spun out of control. Gangster, which also alludes to Apocalypse Now, makes the point that a third of the GIs in Vietnam were drug-addicted, and that they brought the Asian connection home with them. No Country’s Llewelyn Moss provides the Vietnam link, and the pervasive corruption and violence that envelops the austere landscape seems no less begotten of the war.

The reference points forward, too: For Sheriff Bell’s desert county is clearly a parable of Iraq, with its hapless would-be peacemaker overwhelmed by the rival gangs shooting it out among one another. At the end, war-weary and baffled, the sheriff takes retirement and leaves the land to its fate. That hasn’t happened yet with Uncle Sam, but— be patient, if you can— it will.

It is Lumet in Before the Devil, though, who deserves the last word. Russell Crowe’s Richie Roberts is the Calvinistically honest cop who, proof against all corruption, symbolizes our ultimate innocence; Tommy Lee Jones’s Sheriff Bell is at least honorably defeated, as we hope to be in Iraq. But the world can go completely dark, too, as Lumet suggests, and evil rule the day. In such a world, vengeance is possible, but not justice. And vengeance can come home.

Three stylish new neo-noir films

ROBERT ZALLER

It’s not my imagination, is it, but the less we see of real gore, the more addicted we seem to be to the cinematic kind. I haven’t seen a scratch on an American soldier this year except in Ken Burns’s The War, yet the numbers tell me more Americans have died in Iraq and Afghanistan this year than in any previous year since 9/11. Blood will out, though, even if only at the multiplex.

Ridley Scott and the Coen brothers, Ethan and Joel, are veteran bloodletters, so the wetwork in American Gangster and No Country for Old Men is little cause for surprise. Sidney Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, however, is far and away the darkest film of his career, and the near-simultaneous arrival of all three films at area screens suggests a neo-noir revival of sorts.

In a long-forgotten essay, I once traced the representation of violence in American film from the post-World War II era to the late ’70s. Needless to say, film violence has been alive and well since— indeed, so formulaic as to defeat all attempts at commentary. The difference now is that we are once again at war, but a war that, sanitized to the point of being virtually unreportable, has also proved all but unrepresentable. We must look elsewhere to see what is seeping through the carpet.

Bad father, model avenger

Only Before the Devil is more or less contemporary in its setting. Andy Hanson (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman), a Manhattan broker with an ED problem, a heroin habit and a kid’s grudge against his parents, conceives the perfect crime to foil the discovery of his embezzlements: He will rob his parents’ jewelry store. He enlists his younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke) in the caper— all in the family— but when the latter subcontracts the work, everything goes wrong. Dad (Albert Finney) is left a widower, and gradually conceives a suspicion. Finney has been a bad father, as he confesses to Andy; but he proves a model avenger.

The film’s mayhem is actually limited, but it’s shocking enough when it comes. The real violence, however, lies coiled in the family relationship; and what comes out, Lumet suggests, is only a glimpse of what the heart contains within. In a key scene, Finney is taunted by an old colleague who tells him that the world is divided between those who can profit from its evil and those who are merely its victims. The Devil certainly does know when you’re dead.

Fargo South, with one difference

In No Country for Old Men, based on Cormac McCarthy's novel and set in the west Texas of 1980, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) discovers the carnage of a drug deal gone bad, but not before a local civilian, Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), arrives to make off with the swag. Llewelyn is a Vietnam vet and handy with a gun, but he is in over his head against the stone killer (Javier Bardem) who pursues him to retrieve it. Bardem’s Anton Chigurh is a self-styled angel of death who gives his prospective victims a coin-toss chance for life, but he’s so proficient at his trade that not even Woody Harrelson can stop him.

All of this, down to the psycho assassin, is familiar enough from the Coen brothers, and No Country could almost be titled Fargo South. The difference lies not in the bad guys, but in Sheriff Bell, the good one. In Fargo, violent crime takes a rural community by surprise, but Frances McDormand’s lady cop patiently tracks her villains down, knowing that Nordic persistence and attention to detail will get the job done. Sheriff Bell’s county, however, with its elegant desert vistas (superbly photographed by Roger Deakins), has turned into a shooting gallery, and no possibility of order remains.

Familial corruption, yet again

American Gangster is a reprise, too, in this case of the French Connection movies of the 1970s— there’s even an insider reference to Fernando Rey, of “Frog One” fame. As in No Country, drug wars provide the context; as in Before the Devil Knows, familial corruption is the driving theme. If No Country is visually stunning in its breadth, Ridley Scott’s Vietnam-era Harlem, phantasmagoric and raw, virtually implodes its space.

Denzel Washington has more on-screen physical presence than any actor of his generation, and his Frank Lucas, based on the real-life drug kingpin, is an Oscar-worthy performance. Russell Crowe, as the one honest cop on the force in two states, has the unenviable acting task of avoiding Al Pacino’s Serpico and Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle. Pitching himself somewhere in between, he does what he can with an overworked and underwritten role. (Carla Gugino is terrific as his suffering wife, though, and almost pulls enough character through for both of them.) But we’ve seen it before; so why again?

Seeds planted in Vietnam, and Iraq too

The why, both in Gangster and No Country, is a war spun out of control. Gangster, which also alludes to Apocalypse Now, makes the point that a third of the GIs in Vietnam were drug-addicted, and that they brought the Asian connection home with them. No Country’s Llewelyn Moss provides the Vietnam link, and the pervasive corruption and violence that envelops the austere landscape seems no less begotten of the war.

The reference points forward, too: For Sheriff Bell’s desert county is clearly a parable of Iraq, with its hapless would-be peacemaker overwhelmed by the rival gangs shooting it out among one another. At the end, war-weary and baffled, the sheriff takes retirement and leaves the land to its fate. That hasn’t happened yet with Uncle Sam, but— be patient, if you can— it will.

It is Lumet in Before the Devil, though, who deserves the last word. Russell Crowe’s Richie Roberts is the Calvinistically honest cop who, proof against all corruption, symbolizes our ultimate innocence; Tommy Lee Jones’s Sheriff Bell is at least honorably defeated, as we hope to be in Iraq. But the world can go completely dark, too, as Lumet suggests, and evil rule the day. In such a world, vengeance is possible, but not justice. And vengeance can come home.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller