Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

How to ride a warhorse

The Philadelphia Orchestra presents 'Yannick and Emanuel Ax' (first review)

How is classical music doing? It depends on whose hands it’s in. Wednesday night’s gala Carnegie Hall opening of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s new season featured a suite from a Broadway musical, another from a film score, and a deconstruction of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue at the hands of Lang Lang and Chick Correa.

That program, and its performance, showed two disturbing trends: the blurring of lines between the orchestra and the Philly Pops, and the tendency of trendy performers to pull great works apart like taffy to exhibit their virtuosity. Music has to make its living like everything else, and artists have to have interpretive freedom, but there are lines you cross at your peril.

Obviously, this isn’t merely a local problem; consider Alan Gilbert’s tenure at the New York Philharmonic. Gilbert came aboard with plans to explore new and neglected repertory. He left for a less prestigious post in Europe after progressively dumbing down the Philharmonic’s programs and seeing the renovation of its hall (a long saga in Philadelphia, too) put off and finally abandoned.

Well, excuuuuse me

The serious season did begin Friday. Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the orchestra in major works by Mozart and Tchaikovsky and the local premiere of a new work by Texas-born composer Wayne Oquin, a mini-concerto for organ and orchestra titled Resilience, featuring the redoubtable Paul Jacobs. This last work, which opened the program, had an exuberant feel and featured delicately textured exchanges between the organ and different solo instruments and choirs. Jacobs’s pedal-point cadenza near the end of the work exhibited genuine virtuosity.

It is hard to pick a genre in which Mozart excelled more than any other, but no one embodied the concept of soloist and orchestra more perfectly than he did in his mature piano concertos. The last of these, No. 27 in B-flat, begins with an extended orchestral introduction. The piano slips seamlessly into the proceedings at its first entrance. With pauses only for its cadenzas and the occasional instrumental solo, it creates a sublimely integrated texture for an unflagging flow of invention, figuration, and dialogue.

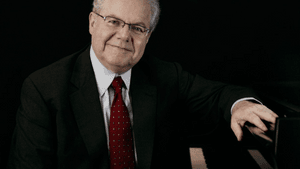

Soloist Emanuel Ax has been a happy fixture for Philadelphia Orchestra audiences since his first appearance in 1975. This will be a Mozart year for him, with performances of six of the concertos with the orchestras of both Saint Louis and Sydney. Ax remains a formidable technician and his performances have the authority of long devotion. He was in particularly fine form in the B-flat major, assertive and even occasionally imperious, but never exceeding proper proportion. The only sour note came not onstage but on paper, in the program, which invited us at one point to think of “Steve Martin playing a banjo with a fake arrow piercing his head.” I passed on that.

The longest Fourth

The orchestra had the stage to itself in Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. This work, although solidly ensconced in the repertory, is less performed than it once was, partly because the first three symphonies, once virtually ignored, now compete with the latter three for attention. The Fourth dates from a difficult time in Tchaikovsky’s life, when he made a brief but disastrous foray into marriage. It is easy enough to read tribulation in some of its more overheated passages, but I think it’s best heard as a work of striking range and expressiveness within a carefully plotted structure, and an important step in his maturation as a symphonist.

The orchestra was beautifully responsive, with richness in the brass, superb highlights in the winds, and finesse in the strings, particularly in the Scherzo’s sustained pizzicati. Nézet-Séguin, in introductory remarks, noted it was his first performance of the Fourth with the orchestra and, for him, an opportunity to rethink the work. There were crisp attacks and effectively introspective moments but also evidence of an increasing mannerism, with exaggerated contrasts of volume and tempo. Slower passages, particularly in the Andantino, were taken with a deliberation that reminded one of Christoph Eschenbach, whereas faster ones were often given the whip.

The result was, at 45 minutes, the longest Fourth I have ever heard. Nézet-Séguin slowed some of his passages nearly to a full stop, which can work in Mahler but, except in the Pathétique symphony, does not for Tchaikovsky. The contrast of this with other passages taken at a gallop made for a choppiness that adversely affected the work as a whole. It is an indulgence Nézet-Séguin would do well to check.

To read Linda Holt's review, click here.

What, When, Where

Yannick and Emanuel Ax. Resilience for Organ and Orchestra, by Wayne Oquin, Paul Jacobs, organ; Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat major (K. 595), by Mozart, Emmanuel Ax, piano; Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36, by Tchaikovsky. The Philadelphia Orchestra. October 6-8, 2017, at the Kimmel Center's Verizon Hall, B300 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 893-1999 or philorch.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller