Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

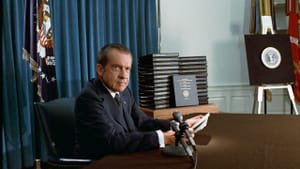

Barbarians at the Watergate: John Dean and the new Nixon tapes

'The Nixon Defense' by John Dean

"The worst thing a guy can do, there are two things, each is bad: One is to lie, and the other one is to cover up. If you cover up, you're going to get caught." (President Richard Nixon to John Ehrlichman, July 19, 1972)

As chaotic human events dissolve from immediate, contemporaneous news into memory and recorded history, they inevitably assume a narrative structure, a consensus of interpretation that becomes the generally accepted version of things. That narrative arises partly from historians, as they study records and unearth previously unavailable sources; from popular culture, as films, books, and television shows attempt to depict and dramatize the past; and even from the current zeitgeist, as historical events are massaged to support or refute various agendas (e.g., Ronald Reagan singlehandedly ended the Cold War). Like seeing the face of Jesus in a piece of burnt toast, it springs from the universal human need to find meaning and purpose in an essentially meaningless and purposeless universe by constructing easily understandable and digestible stories, finding patterns where none exist.

And so it is with Watergate, generally regarded as the Worst Political Scandal of American History. Forty years ago this month, that scandal forced the resignation of a U.S. president and devastated the American people's faith in the credibility of their government like nothing before or since.

Now we have two generations of young Americans who weren't even alive yet when Nixon, Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and their cronies were skulking and scheming in the corridors of the White House. For those citizens — with no memories of the televised Senate hearings, the breathless evening news reports, the terse White House denials — Watergate is all just history. It's also the archetypal example of a sinister conspiracy, a notion promulgated by countless media depictions and references, beginning with the 1976 film All the President's Men, in which Hal Holbrook's Deep Throat lurks in shadowy parking garages at 2 AM and warns Robert Redford's Bob Woodward that the evil plot "involves the entire U.S. intelligence community . . . it's incredible . . . it leads everywhere . . . your lives are in danger."

A new narrative

But while the distance of time can obscure and distort history, it can also provide new perspective and insight. That's the motivation behind John Dean's new book, The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It, based on over a thousand new transcriptions of every Watergate-related conversation from the Nixon tapes, at least 600 of which no one had ever bothered to analyze. Informed by Dean's unique historical role as a participant, coconspirator, and legal witness in the whole affair, it's a rich treasure trove for anyone fascinated by the complex Shakespearian personage that was Richard M. Nixon.

Dean structures The Nixon Defense in narrative form, with transcript material set off in quotation marks with Dean providing background. It's an effective approach: As any researcher will tell you, poring over verbatim transcripts of conversations can get tedious. But The Nixon Defense reads almost like a political suspense novel.

Contrary to common perceptions, Dean makes it clear that Watergate was hardly a cunningly conceived master plan guided by Richard Nixon like a James Bond archvillain. Rather, it was a saga of monumental ineptitude and a shameful readiness to place politics before legality, growing from botched burglaries and amateurish schemes that steadily metastasized into the "cancer on the presidency" that took Nixon down, all spurred by his own paranoia and egregious abuses of power.

Puncturing canards

Dean elaborated on these themes in an appearance at the Free Library last month, puncturing a few other accepted canards of the Watergate mythos in the process. For one thing, he observed that while G. Gordon Liddy, the mastermind of the Watergate burglary and various other shady deeds, liked to fancy himself as a James Bond type, "he was hardly even at the level of Maxwell Smart." And that famous 18-1/2 minute gap in the tapes, the one that supposedly contained the key to the entire mystery? Not really that big a deal, Dean says, making a convincing case that there was nothing in those lost minutes that wasn't already present in other tapes and evidence. Nor was the famous "smoking gun" Nixon-Haldeman conversation of June 23, 1972 quite as significant as generally believed. "The smoking gun was only firing blanks," Dean concludes.

But don't let Dean's title mislead you into thinking that Nixon's actions can ultimately be justified. The point of the book is that Nixon's "defense" was nothing more than an elaborate construct of willful legal obstructions, venal manipulations, and byzantine stratagems laced with a generous dose of wishful thinking. It was doomed from the start, even if Nixon failed to admit it to himself until almost all his allies, cronies, and supporters had abandoned him or fallen under the weight of law.

In July 1972, before the scandal had barely registered on the public consciousness, Nixon remarked to Haldeman, "I have a feeling Watergate's going to be a nasty issue for a few days." Perhaps if he had recognized at the time the degree of self-deception contained in that offhand comment, history would have been markedly different.

What, When, Where

The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It. By John Dean. Viking, 2014, 784 pp., $35.00.

Free Library of Philadelphia Author Events: http://libwww.freelibrary.org/authorevents/

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Mark Wolverton

Mark Wolverton