Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Lasting impressions

The Fabric Workshop and Museum presents 'Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture'

You can meet architect Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974) in the Fabric Workshop and Museum's new exhibition The Power of Architecture, but to meet the man, watch his son Nathaniel's 2003 documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey.

Though he was internationally recognized as a visionary, relatively few of the Philadelphia-based architect’s designs reached completion. Often, Kahn sabotaged projects by refusing to compromise. This exhibition is dense with material documenting the built and unbuilt portfolio, as well as commentary from those who knew him.

Futuristic city planning

One of Kahn’s most interesting unbuilt structures is City Hall Tower, designed in the early 1950s with architect Anne Tyng. It was to have stood beside, and taken over functions of, Philadelphia’s City Hall, and even on paper looks radical: a 600-foot zigzag, twisting toward the sky. The design was inspired by the double-helix structure of DNA, discovered in 1953.

The tower was part of Kahn’s work in urban development; he worked with Edmund Bacon, who directed the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970. At the time, cities were showing the adverse effects of age, poverty, cars, and suburbanization, and Philadelphia became a laboratory for renewal.

Documents underscore Kahn’s body of work in urban planning, though little of Philadelphia’s redevelopment shows his influence. Ultimately, Bacon and Kahn’s personalities proved incompatible. An interview in Nathaniel Kahn’s film reveals just how deep the task-oriented Bacon’s frustration still ran. While recalling the working relationship, Bacon, then 93, sputtered, “Totally insensitive, totally impractical… pure ignorance!”

In hindsight, Kahn’s ideas may have just been premature. For example, he proposed ringing Center City with garages to create a pedestrian zone. The idea has since been tried in limited ways and has proven popular.

Philadelphia building brings international fame

Philadelphia was Kahn’s home from age five, when his parents emigrated from Estonia. At Central High School, an architecture course introduced him to his passion, which he pursued at the University of Pennsylvania.

Appropriately, a Penn building brought him international attention: the Richards Medical Research and Biology Building (1957-65), Kahn’s first expression of what he termed “servant” and “served” spaces. Servant spaces held building functions, which at Richards included quarters for lab animals. Each "servant" tower supported three towers of "served" space: offices and labs. In 2009, Richards and the connecting David Goddard Laboratories, also by Kahn, were declared a National Historic Landmark.

That project prepared Kahn for the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California (1959-1965). According to Nathaniel, Salk was the only finished project with which his father was completely happy and the only one on which he did not lose money. Several things went right: Kahn was given a free hand by his client, scientist Jonas Salk, and the site, overlooking the Pacific, was ideal for Kahn, who believed nature and design were inseparable.

Giver of light

In Fort Worth, Texas, Kahn designed the Kimbell Art Museum consistent with his belief that, “Structure… is the giver of light.” Sunlight channels into the galleries through a roof of semicircular concrete vaults. At the apex of each vault, a narrow slit, cut lengthwise, admits light, and reflectors redirect it, providing natural, ever-changing illumination.

Residential spaces

Housing was a focus throughout Kahn’s career. In the 1930s, he formed the Architectural Research Group to study slum clearance and reconstruction. Though his last major public-housing project, West Philadelphia’s Mill Creek Homes (1951-1963) was demolished in 2003, it employed features still in favor, such as green walkways and courtyards.

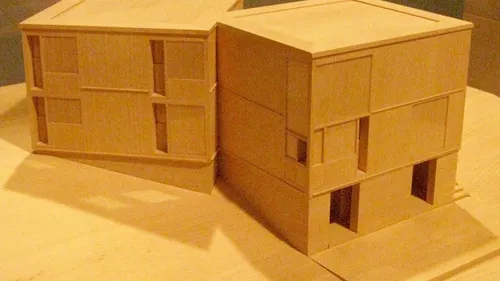

Private homes by Kahn still exist, including the Norman and Doris Fisher house in Hatboro, Pennsylvania. Built in the 1960s, it exemplifies Kahn’s characteristic reliance on geometric forms: cubes and spheres, angles and planes, solids and voids. Fisher consists of two large cubes, one holding private spaces (bedrooms and baths), the other public rooms.

Consulting nature

“Consult nature,” Kahn instructed a master class. “Honor the material which you use.” He was indelibly inspired by the ancient ruins he saw while serving as architect-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome. Kahn desired his buildings, though modern in form, to have the presence of ruins.

From residences to academic facilities to public buildings — including his last great commission, the capitol building of Bangladesh in Dhaka (1962-1983) — Kahn’s artistry and sensitivity to site, materials, and purpose are evident.

Three families

Thus, his treatment of humans is difficult to reconcile. Nathaniel Kahn’s film centers on something the exhibit only hints at: Kahn had three families, all living in the Philadelphia area. He married Esther in 1930 and they had a daughter, Sue. In the early 1950s, a relationship with Anne Tyng produced another daughter, Alex. In the late 1950s, he developed a relationship with Nathaniel’s mother, Harriet, who worked in Kahn’s Walnut Street architectural office. Nathaniel was just 11 when Kahn died in 1974. The documentary grew out of his yearning to know more about his father.

Given the circumstances, there’s remarkably little anger expressed toward Kahn on the part of his children or their mothers (Esther died before the film was made). Mostly, there is disappointment. Nathaniel’s mother never stopped believing, until Kahn died in 1974 of a sudden heart attack in Penn Station, that he was on his way to live with them.

Even colleagues, not all of whom knew of the situation, spoke kindly of Kahn, with little condemnation. Said one: “He was a great man whom we forgave because of the things he was doing.”

Of Kahn, the acclaimed architect Frank Gehry said, “He thought of a brick as having a conscience and a life.” If only he had treated the women and children in his life with as much consideration.

To read an essay by Dan Rottenberg on the Fabric Workshop's Louis Kahn exhibition, click here.

What, When, Where

Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture. Through November 5, 2017, at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, 1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia. (215) 561-8888 or fabricworkshopandmuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.