Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Wheeling and dealing, '60s style

"The Columnist' and "The Best Man' on Broadway

Mitt Romney might well seek consolation in the theater these days. On Broadway, he'll find more than one public figure whose past has also caught up with him. And while these politicians' misdeeds may seem benign compared to Romney's alleged stint as a teenage bully and (possibly) homophobe, the consequences are equally significant.

These politicos can be found wheeling and dealing in neighboring productions of The Columnist and The Best Man on Broadway, where the spring theater season seems to be imitating the current political one in terms of accusations, revelations and other campaign machinations. But rest assured that Broadway's characters are far more piquant than the colorless candidates in this spring's Republican race.

The rise and fall of Joseph Alsop, political journalist par excellence of the JFK era, is a long-awaited saga in the retelling. David Auburn's absorbing new play, The Columnist, dramatizes the story of the ultimate political insider.

Alsop (1910-1989) was the Cole Porter of politics "“ talented, flamboyant and elitist. In a career that spanned several presidents (from FDR to Johnson), he rose to unprecedented heights during John F. Kennedy's administration. In one of the play's early scenes, set on the night JFK was elected, Alsop sits in his Washington D.C. suite at 2 a.m., minutes before a surprise visit by the president-elect himself. It was an event that made Alsop's status as JFK's closest advisor all but official.

Isolated over Vietnam

Alsop was WASPish, stylish, witty, and "establishment" (he was a cousin of Eleanor Roosevelt and educated at Groton and Harvard), and so he came to personify the glamour, excitement and energy of the Kennedy years. He was also outspoken, opinionated and deeply feared. At the zenith of his power, his syndicated political column appeared in more than 190 newspapers, and he traveled the world in VIP style.

Inevitably his outspoken and opinionated style generated enemies— and that's the stuff of Auburn's play. Alsop's devout hawkishness on Vietnam alienated David Halberstam, a talented young New York Times journalist (and a character in the play) who became one of Alsop's bitter opponents. James Reston and other influential journalists of the day soon join Halberstam's camp and form a steadfast anti-Alsop alliance.

Then comes Kennedy's assassination in Dallas and, with it, Alsop's dramatic reversal of fortune. Without JFK, Alsop's position in the Washington establishment begins to slip.

Entrapped by the KGB

Then the other shoe drops. Alsop's tryst with a male prostitute in a Moscow hotel, dramatized in Act I, turns out to have been a KGB entrapment, which catches up with Alsop in Act II. Photos are leaked to his enemies in the press.

Cornered, Alsop becomes more venomous and vindictive. His hawkishness on Vietnam intensifies, as does his paranoia (he alleged that Lyndon Johnson was tapping his phone). One by one, Alsop turns on those around him"“ including his devoted wife and loyal brother Stewart (they had co-authored a column for decades).

"I love my country," sighs a defeated Alsop in the end. "I just don't care very much for the people in it."

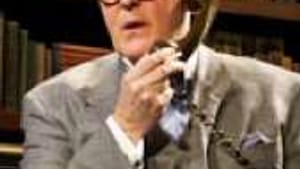

In the title role, John Lithgow brandishes a signature cigarette holder, sports a signature bow tie and owlish glasses, and generally cuts the quintessential figure of power and privilege to perfection. It's a dying breed of elitism, now almost extinct in the Internet Age, when anyone with an opinion can find an audience. Still, I couldn't help savor that bittersweet taste of nostalgia for a glamorous political era when the power of the press was wielded by a select few.

Ruining reputations

Alsop's life was fictionalized in a 1967 novel called Washington D.C., by Gore Vidal, another elitist of the Kennedy era. Coincidently (and ironically), Vidal is also the author of The Best Man, the other political play currently on Broadway, set also in the 1960s. Unlike Auburn's Alsop, Vidal's stage politicians are fictitious. Nevertheless, they play the same perilous games, in which reputations can be ruined with the dialing of a telephone.

Vidal's smart comedy/drama is set at a national party convention in Philadelphia in July 1960, in an era when conventions actually meant something and balloting wasn't a foregone conclusion. Vidal's fictitious candidates, William Russell (played by John Larroquette, a Bill Clinton look-alike) and Joe Cantrell (played by Eric McCormack, a Rick Santorum look-alike), are running a heated primary race, and Russell seems likely to win the nomination on the first ballot.

But the devious Cantrell has uncovered a secret in Russell's past"“ a hospitalization for a nervous breakdown"“ which he intends to leak to the press and turn the tide of the nomination. Meanwhile, secret information lands in Russell's hands revealing a gay relationship that his opponent Cantrell allegedly had years ago in the army. But Russell declines to use it. He wants to win fair and square.

Star cameos

Whether they're moralistic or opportunistic, righteous or devious, these politicos are engaging to watch as they play their Machiavellian games. Even with stock characters who verge on caricature (e.g., the candidate's wives), the plot offers some surprising twist and turns.

This entertaining and satisfying production also boasts two old-fashioned star cameos: the charismatic James Earl Jones as the wily former president, and the irrepressible Angela Lansbury as a political grande dame. Director Michael Wilson turns the entire Schoenfeld Theatre into Philadelphia's (former) Convention Hall, with banners, flags, TV screens, ushers sporting campaign hats, you name it.

Romney's skeletons

As this relevant revival of The Best Man shows, negative material can always be found to cast new light on a rival politician in the throes of a presidential campaign. Mitt Romney's transporting a family dog on the roof of a car for 12 hours during a vacation trip or indulging in lavish home expenses (like a car elevator) may not rise to the level of a serious misdemeanor, but his bullying incident in prep school very well might. What we've learned in the past half-century since The Best Man is that a candidate's past misdeeds don't shed as much light on his character as the way he responds when the old deeds are dredged up.

How Romney handles these allegations— serious or small — may indeed determine who "the best man" is in 2012, whether that man wins or not. Maybe someone should buy Romney some theater tickets.

These politicos can be found wheeling and dealing in neighboring productions of The Columnist and The Best Man on Broadway, where the spring theater season seems to be imitating the current political one in terms of accusations, revelations and other campaign machinations. But rest assured that Broadway's characters are far more piquant than the colorless candidates in this spring's Republican race.

The rise and fall of Joseph Alsop, political journalist par excellence of the JFK era, is a long-awaited saga in the retelling. David Auburn's absorbing new play, The Columnist, dramatizes the story of the ultimate political insider.

Alsop (1910-1989) was the Cole Porter of politics "“ talented, flamboyant and elitist. In a career that spanned several presidents (from FDR to Johnson), he rose to unprecedented heights during John F. Kennedy's administration. In one of the play's early scenes, set on the night JFK was elected, Alsop sits in his Washington D.C. suite at 2 a.m., minutes before a surprise visit by the president-elect himself. It was an event that made Alsop's status as JFK's closest advisor all but official.

Isolated over Vietnam

Alsop was WASPish, stylish, witty, and "establishment" (he was a cousin of Eleanor Roosevelt and educated at Groton and Harvard), and so he came to personify the glamour, excitement and energy of the Kennedy years. He was also outspoken, opinionated and deeply feared. At the zenith of his power, his syndicated political column appeared in more than 190 newspapers, and he traveled the world in VIP style.

Inevitably his outspoken and opinionated style generated enemies— and that's the stuff of Auburn's play. Alsop's devout hawkishness on Vietnam alienated David Halberstam, a talented young New York Times journalist (and a character in the play) who became one of Alsop's bitter opponents. James Reston and other influential journalists of the day soon join Halberstam's camp and form a steadfast anti-Alsop alliance.

Then comes Kennedy's assassination in Dallas and, with it, Alsop's dramatic reversal of fortune. Without JFK, Alsop's position in the Washington establishment begins to slip.

Entrapped by the KGB

Then the other shoe drops. Alsop's tryst with a male prostitute in a Moscow hotel, dramatized in Act I, turns out to have been a KGB entrapment, which catches up with Alsop in Act II. Photos are leaked to his enemies in the press.

Cornered, Alsop becomes more venomous and vindictive. His hawkishness on Vietnam intensifies, as does his paranoia (he alleged that Lyndon Johnson was tapping his phone). One by one, Alsop turns on those around him"“ including his devoted wife and loyal brother Stewart (they had co-authored a column for decades).

"I love my country," sighs a defeated Alsop in the end. "I just don't care very much for the people in it."

In the title role, John Lithgow brandishes a signature cigarette holder, sports a signature bow tie and owlish glasses, and generally cuts the quintessential figure of power and privilege to perfection. It's a dying breed of elitism, now almost extinct in the Internet Age, when anyone with an opinion can find an audience. Still, I couldn't help savor that bittersweet taste of nostalgia for a glamorous political era when the power of the press was wielded by a select few.

Ruining reputations

Alsop's life was fictionalized in a 1967 novel called Washington D.C., by Gore Vidal, another elitist of the Kennedy era. Coincidently (and ironically), Vidal is also the author of The Best Man, the other political play currently on Broadway, set also in the 1960s. Unlike Auburn's Alsop, Vidal's stage politicians are fictitious. Nevertheless, they play the same perilous games, in which reputations can be ruined with the dialing of a telephone.

Vidal's smart comedy/drama is set at a national party convention in Philadelphia in July 1960, in an era when conventions actually meant something and balloting wasn't a foregone conclusion. Vidal's fictitious candidates, William Russell (played by John Larroquette, a Bill Clinton look-alike) and Joe Cantrell (played by Eric McCormack, a Rick Santorum look-alike), are running a heated primary race, and Russell seems likely to win the nomination on the first ballot.

But the devious Cantrell has uncovered a secret in Russell's past"“ a hospitalization for a nervous breakdown"“ which he intends to leak to the press and turn the tide of the nomination. Meanwhile, secret information lands in Russell's hands revealing a gay relationship that his opponent Cantrell allegedly had years ago in the army. But Russell declines to use it. He wants to win fair and square.

Star cameos

Whether they're moralistic or opportunistic, righteous or devious, these politicos are engaging to watch as they play their Machiavellian games. Even with stock characters who verge on caricature (e.g., the candidate's wives), the plot offers some surprising twist and turns.

This entertaining and satisfying production also boasts two old-fashioned star cameos: the charismatic James Earl Jones as the wily former president, and the irrepressible Angela Lansbury as a political grande dame. Director Michael Wilson turns the entire Schoenfeld Theatre into Philadelphia's (former) Convention Hall, with banners, flags, TV screens, ushers sporting campaign hats, you name it.

Romney's skeletons

As this relevant revival of The Best Man shows, negative material can always be found to cast new light on a rival politician in the throes of a presidential campaign. Mitt Romney's transporting a family dog on the roof of a car for 12 hours during a vacation trip or indulging in lavish home expenses (like a car elevator) may not rise to the level of a serious misdemeanor, but his bullying incident in prep school very well might. What we've learned in the past half-century since The Best Man is that a candidate's past misdeeds don't shed as much light on his character as the way he responds when the old deeds are dredged up.

How Romney handles these allegations— serious or small — may indeed determine who "the best man" is in 2012, whether that man wins or not. Maybe someone should buy Romney some theater tickets.

What, When, Where

The Columnist. By David Auburn; Daniel Sullivan directed. Through July 1, 2012 at Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, Manhattan Theatre Club, 261 West 47th St., New York. www.thecolumnistbroadway.com.

The Best Man. By Gore Vidal; Michael Wilson directed. At Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, 236 West 45th St., New York. (212) 239-6200 or www.thebestmanonbroadway.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.