Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Sleepwalking toward Armageddon

"Take Shelter': Prophecy vs. lunacy (1st review)

Take Shelter, the second feature film directed by Jeff Nichols, has much in common superficially with Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, beginning with the image of a tree swaying a bit ominously in the wind. As in Malick's film, the plot revolves around a small nuclear family with a disturbed breadwinner haunted by his past and a hopeful, submissive wife, the latter played in both films by the suddenly ubiquitous Jessica Chastain.

Take Shelter is set in Ohio and The Tree of Life in Texas, but their relentlessly flat and naked landscapes seem, to the casual eye, almost interchangeable, and in both films the physical environment is critical to the plot. I'm not suggesting more than interesting coincidence here, but Nichols does appear to have studied some of Malick's earlier work with profit.

Malick's film is rooted in his adult male protagonist, O'Brien, whose compulsive and ultimately destructive behavior is refracted through the eyes of his elder son; and even though Malick continually works to subvert our narrative expectations, the father-son conflict remains at its core.

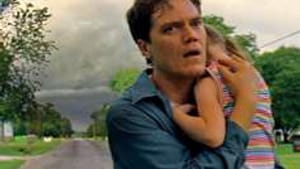

No such issue appears for Take Shelter's Curtis LaForche (Michael Shannon), whose deaf child, Hannah (Tova Stewart), brings out only paternal tenderness and concern. Indeed, Curtis is in every way a good guy; and, as his envious friend Dewart (Shea Whigham) remarks, he has what looks like a good life: a decent job drilling at a local sand mine; a comfortable home; a loving wife, Samantha; and a loyal dog.

Storm clouds

True, there's the special-needs child who's on a waiting list for a cochlear implant, and the wife who'd like some breast augmentation. But Curtis even has decent health insurance, and all dreams, it seems, can come true.

The only problem is these nightmares and visions Curtis keeps having. Storm clouds suddenly loom above him, shedding a viscous rain. Birds, too, appear out of nowhere, wheeling and dispersing in dense pinwheel patterns.

(I assume this latter effect was generated by computer, but in fact I once saw such an avian pattern myself above a river in western India, and was as thoroughly spooked by it as Curtis is in Take Shelter.)

Curtis's dreams, though, are even more petrifying than his visions, and typically involve the threat of harm to his daughter. When his dog attacks him in one dream, the trauma doesn't subside with dawn, and he puts the pet outside.

Assisted living

Bad dreams are one thing, but when Curtis realizes that no one else shares his waking hallucinations, he draws the logical inference: He's losing his sanity. This is the more plausible in that his mother, Sarah (Kathy Baker), had succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia at just the age Curtis is now, his mid-30s.

In one very good scene, Curtis visits Sarah in an assisted-living facility, hoping to learn whether his symptoms are replicating hers. What he discovers is inconclusive, but the fate that may await him seems all the more chilling: not raving lunacy, but a mild, medicated detachment that suggests a living death.

Curtis seeks help at a local clinic, but finds he can hardly afford the sleeping pills that are all it can offer, let alone the expensive medical treatment he knows he needs. At the same time, however, he takes out a risky loan to build an elaborate tornado shelter behind his house, risking his job in the process.

We are invited to take this project as a projection of his paranoia; certainly, his family and coworkers regard it as such. But how does it seem to Curtis himself?

Old Testament wrath

The Curtis who fears he is ill must presumably regard this new obsession as others do, as a symptom of derangement; but his doggedness in digging a deep and costly hole— the hole that concretizes the disaster he is bringing on himself— also seems to reflect a part of his mind that believes his visions to be not delusional but prophetic.

The film's climactic scene occurs at a local community supper where, challenged and assaulted, Curtis turns on his neighbors with the wrath of an Old Testament figure and warns them of a tempest to come unlike anything they've seen.

A tornado does indeed follow shortly after this speech, and Curtis's new shelter comes in handy for Samantha and Hannah. But blue skies return, and Curtis, finally under a psychiatrist's care, meekly accepts the necessity of treatment in a facility— the first step, as he bleakly realizes, down his mother's road, but one that, as the ultimately decent and caring man he remains, he knows he must submit to.

Prophecy or lunacy?

A last respite is permitted him in the form of a family vacation (though why this risk is taken is unclear). Here, on a peaceful beach, Curtis' vision of the storm returns, but this time not to him alone.

Prophets always appear crazy to others, and sometimes to themselves. When their vision begins to spread, is it truth, or mere shared delusion? Throughout Take Shelter, Jeff Nichols baits the hook both ways for us.

We see the visions and nightmares that torment Curtis as the other characters in the film don't. Are we merely being invited into the recesses of a diseased mind? This glimpse is obviously an unsatisfactory reward for two hours of our patience, and we wait for the cue that will tell us how to take the story as Curtis's life unravels.

Curtis's nightmares are clearly mental events, for we see him wake from each of them in his bed. Perhaps, though, there is really something to his waking visions, and the nightmares simply internalize the dread they provoke? Since the film is seen almost entirely from his perspective, with the camera lingering for long stretches on Michael Shannon's somber, pancake features, surely the character's searching— and ours— will result in something more than a routine psychiatric diagnosis?

Troubling "'normality'

Nichols's success lies in his maintaining the tension between prophecy and lunacy to the end, and refusing to resolve it for us even as he seems to tip his hand. In doing so, he focuses us on the always contested borderland between dream and waking, reality and imagination.

Is there something out there we should be looking at? The images of storm that terrorize Curtis invoke familiar Biblical tropes of divine wrath. But bad weather isn't just a metaphor any more; it's increasingly the fact of our lives.

When Curtis emerges from his shelter after the film's "real" storm, the image he sees— neighbors calmly replacing their lawn and porch furniture; a crew working on a downed power line— is as unsettling to the viewer as any of his nightmare visions. (That we haven't seen any of these things before in the vicinity of the shelter is a point the casual viewer may miss.)

What we see, in short, is a workday return to normality, as if nothing had really happened and life could resume its regular course with a few repairs.

Gore's warning

In the aftermath of a real tropical deluge and a record blizzard experienced within two months of each other— weather events from which recovery is still incomplete— you could be forgiven for concluding that the bizarre illusion of our can-do adaptability in the face of catastrophic climate change is the real hallucination, and the image of casual adjustment that Curtis sees on climbing to the light of day that is the scariest thing in the film.

In An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore (remember him?) tried to hit us over the head with the facts and figures of what we're doing to our perishable planet. Nichols is after something more elusive: the dream-state in which we sleepwalk toward ecological Armageddon. Instead of naming it, Nichols simply shows it through the eyes of an ordinary man who's confused by what he sees and wonders if it's madness.

Nor does Nichols limit himself to the more obvious layers of our disquiet. He gently probes the erosion of job and health security that's also shifting the ground from under our feet, and the sense of a lost moral compass that leaves so many Americans bewildered about the perfidy of our institutions.

The trouble we've made for our planet, Nichols suggests, begins with the trouble we've made for ourselves, which properly begins and ends in our heads. The problem is, though, that the world isn't waiting any longer for us to figure ourselves out.

Take Shelter is not without its flaws. The pacing is slow, and too many points are made twice— or more. The special effects, too, tend to pall after awhile. But Take Shelter is a work of talent and ambition, and the truths it embodies— but doesn't impose— demand urgent reflection.♦

To read another review by Judy Weightman, click here.

Take Shelter is set in Ohio and The Tree of Life in Texas, but their relentlessly flat and naked landscapes seem, to the casual eye, almost interchangeable, and in both films the physical environment is critical to the plot. I'm not suggesting more than interesting coincidence here, but Nichols does appear to have studied some of Malick's earlier work with profit.

Malick's film is rooted in his adult male protagonist, O'Brien, whose compulsive and ultimately destructive behavior is refracted through the eyes of his elder son; and even though Malick continually works to subvert our narrative expectations, the father-son conflict remains at its core.

No such issue appears for Take Shelter's Curtis LaForche (Michael Shannon), whose deaf child, Hannah (Tova Stewart), brings out only paternal tenderness and concern. Indeed, Curtis is in every way a good guy; and, as his envious friend Dewart (Shea Whigham) remarks, he has what looks like a good life: a decent job drilling at a local sand mine; a comfortable home; a loving wife, Samantha; and a loyal dog.

Storm clouds

True, there's the special-needs child who's on a waiting list for a cochlear implant, and the wife who'd like some breast augmentation. But Curtis even has decent health insurance, and all dreams, it seems, can come true.

The only problem is these nightmares and visions Curtis keeps having. Storm clouds suddenly loom above him, shedding a viscous rain. Birds, too, appear out of nowhere, wheeling and dispersing in dense pinwheel patterns.

(I assume this latter effect was generated by computer, but in fact I once saw such an avian pattern myself above a river in western India, and was as thoroughly spooked by it as Curtis is in Take Shelter.)

Curtis's dreams, though, are even more petrifying than his visions, and typically involve the threat of harm to his daughter. When his dog attacks him in one dream, the trauma doesn't subside with dawn, and he puts the pet outside.

Assisted living

Bad dreams are one thing, but when Curtis realizes that no one else shares his waking hallucinations, he draws the logical inference: He's losing his sanity. This is the more plausible in that his mother, Sarah (Kathy Baker), had succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia at just the age Curtis is now, his mid-30s.

In one very good scene, Curtis visits Sarah in an assisted-living facility, hoping to learn whether his symptoms are replicating hers. What he discovers is inconclusive, but the fate that may await him seems all the more chilling: not raving lunacy, but a mild, medicated detachment that suggests a living death.

Curtis seeks help at a local clinic, but finds he can hardly afford the sleeping pills that are all it can offer, let alone the expensive medical treatment he knows he needs. At the same time, however, he takes out a risky loan to build an elaborate tornado shelter behind his house, risking his job in the process.

We are invited to take this project as a projection of his paranoia; certainly, his family and coworkers regard it as such. But how does it seem to Curtis himself?

Old Testament wrath

The Curtis who fears he is ill must presumably regard this new obsession as others do, as a symptom of derangement; but his doggedness in digging a deep and costly hole— the hole that concretizes the disaster he is bringing on himself— also seems to reflect a part of his mind that believes his visions to be not delusional but prophetic.

The film's climactic scene occurs at a local community supper where, challenged and assaulted, Curtis turns on his neighbors with the wrath of an Old Testament figure and warns them of a tempest to come unlike anything they've seen.

A tornado does indeed follow shortly after this speech, and Curtis's new shelter comes in handy for Samantha and Hannah. But blue skies return, and Curtis, finally under a psychiatrist's care, meekly accepts the necessity of treatment in a facility— the first step, as he bleakly realizes, down his mother's road, but one that, as the ultimately decent and caring man he remains, he knows he must submit to.

Prophecy or lunacy?

A last respite is permitted him in the form of a family vacation (though why this risk is taken is unclear). Here, on a peaceful beach, Curtis' vision of the storm returns, but this time not to him alone.

Prophets always appear crazy to others, and sometimes to themselves. When their vision begins to spread, is it truth, or mere shared delusion? Throughout Take Shelter, Jeff Nichols baits the hook both ways for us.

We see the visions and nightmares that torment Curtis as the other characters in the film don't. Are we merely being invited into the recesses of a diseased mind? This glimpse is obviously an unsatisfactory reward for two hours of our patience, and we wait for the cue that will tell us how to take the story as Curtis's life unravels.

Curtis's nightmares are clearly mental events, for we see him wake from each of them in his bed. Perhaps, though, there is really something to his waking visions, and the nightmares simply internalize the dread they provoke? Since the film is seen almost entirely from his perspective, with the camera lingering for long stretches on Michael Shannon's somber, pancake features, surely the character's searching— and ours— will result in something more than a routine psychiatric diagnosis?

Troubling "'normality'

Nichols's success lies in his maintaining the tension between prophecy and lunacy to the end, and refusing to resolve it for us even as he seems to tip his hand. In doing so, he focuses us on the always contested borderland between dream and waking, reality and imagination.

Is there something out there we should be looking at? The images of storm that terrorize Curtis invoke familiar Biblical tropes of divine wrath. But bad weather isn't just a metaphor any more; it's increasingly the fact of our lives.

When Curtis emerges from his shelter after the film's "real" storm, the image he sees— neighbors calmly replacing their lawn and porch furniture; a crew working on a downed power line— is as unsettling to the viewer as any of his nightmare visions. (That we haven't seen any of these things before in the vicinity of the shelter is a point the casual viewer may miss.)

What we see, in short, is a workday return to normality, as if nothing had really happened and life could resume its regular course with a few repairs.

Gore's warning

In the aftermath of a real tropical deluge and a record blizzard experienced within two months of each other— weather events from which recovery is still incomplete— you could be forgiven for concluding that the bizarre illusion of our can-do adaptability in the face of catastrophic climate change is the real hallucination, and the image of casual adjustment that Curtis sees on climbing to the light of day that is the scariest thing in the film.

In An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore (remember him?) tried to hit us over the head with the facts and figures of what we're doing to our perishable planet. Nichols is after something more elusive: the dream-state in which we sleepwalk toward ecological Armageddon. Instead of naming it, Nichols simply shows it through the eyes of an ordinary man who's confused by what he sees and wonders if it's madness.

Nor does Nichols limit himself to the more obvious layers of our disquiet. He gently probes the erosion of job and health security that's also shifting the ground from under our feet, and the sense of a lost moral compass that leaves so many Americans bewildered about the perfidy of our institutions.

The trouble we've made for our planet, Nichols suggests, begins with the trouble we've made for ourselves, which properly begins and ends in our heads. The problem is, though, that the world isn't waiting any longer for us to figure ourselves out.

Take Shelter is not without its flaws. The pacing is slow, and too many points are made twice— or more. The special effects, too, tend to pall after awhile. But Take Shelter is a work of talent and ambition, and the truths it embodies— but doesn't impose— demand urgent reflection.♦

To read another review by Judy Weightman, click here.

What, When, Where

Take Shelter. A film directed by Jeff Nichols. For Philadelphia area theaters and show times, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller