Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

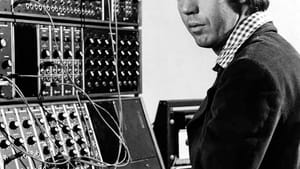

When the Moog was young

‘Synthesizer Pioneer: The Early Electronic Music of Andrew Rudin’ from Centaur Records

The Moog Synthesizer became an international sensation in 1968, when Wendy Carlos released the best-selling album Switched-On-Bach, featuring a variety of arrangements of the Baroque master for the new-fangled instrument. But Carlos wasn’t first to the Moog: the music of a Penn graduate student predated her release by several years. A 2019 album, Synthesizer Pioneer: The Early Electronic Music of Andrew Rudin, gathers this work for new and longtime fans.

Andrew Rudin’s “abstract opera,” Il Giuco, premiered at a 1966 concert of the Philadelphia Composer’s Forum, alongside music by George Crumb and Vincent Persichetti. It was, according to the inventor himself, the first large-scale composition for the Moog Synthesizer.

Meet the “Moog-a-phone”

Rudin first encountered the instrument in New York. In the spring of 1964 he traveled to see the spectacular Alwin Nikolais Dance Theatre, where one of his high school friends was a member. Following a hallowed tradition among poor, starving students, he volunteered to usher so that he could see the show gratis, and afterward was invited backstage, where he met Nikolais, then and now one of the great masters of modern dance.

Nikolais, who composed his own music in the musique concrete (an abstract style utilizing prerecorded sounds) in the manner of Stockhausen, among others, had just acquired a new toy. He called it his Moog-a-phone, a synthesizer invented by the eponymous Robert Moog. The young composition student was enthralled by the new device, which was designed to mimic the sounds of traditional instruments, thus fostering the rumor that it had been conceived of by the music business as a way to supplant unionized session musicians. It also produces uniquely electronic sounds, and that is the aspect of the Moog Synthesizer that Rudin seizes upon in his creations.

Dreamy, wry, exuberant

In the years since these early works, Rudin has mainly written in a traditional manner for traditional ensembles, albeit in a voice infused with contemporary harmonic language. The nascent pieces featured on Synthesizer Pioneer tend to emphasize Rudin’s fondness for dramatic musical interplay and theatricality, overtly so in the two works referred to as abstract operas and in three sets of “porcelain dialogues.” Of course, any conversations in these works will be in a tongue unknown to anyone other than the composer, but therein lies their charm. Imagine watching a Fellini film without the subtitles; you may not understand the words, but the context of the dynamic phrasing and vocal inflection gives the material meaning.

Rudin has created many moments of mysterious beauty and intriguing textures in this music, but the chief effect is of wit and whimsy. In this sense, there seems to be a strong connection to the choreography of Nikolais, whose hypnotic stagecraft was often exotically dreamy but also delightfully wry. Both Rudin and Nikolais (who collaborated on four works) achieved a sense of physicality that transcends their respective mediums, in the manner of abstract painting, and in the case of the newly collected sounds of Rudin, served up with a healthy dollop of youthful exuberance.

What, When, Where

Synthesizer Pioneer: The Early Electronic Music of Andrew Rudin. Centaur Records, February 8, 2019. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.