Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Searching for meaning in Meg Foley's "slip'

But what do those moving bodies mean?

An encounter with Meg Foley

"The desire to preserve and represent the performance event is a desire we should resist. For what one otherwise preserves is an illustrated corpse..."

-Peggy Phelan, from Mourning Sex: Performing Public Memories

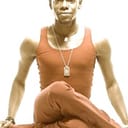

JAAMIL OLAWALE KOSOKO

I first encountered the choreography of Meg Foley at an American Dance Festival Open Showing in Durham, NC. We were dance students from opposite ends of the nation. She was finishing her studies at Scripps College (an all women’s college in California) while I was beginning my senior thesis at Bennington College (a former all women’s college in Vermont). Although our performance esthetics were (and still are) quite different, I was drawn to her movement ideas then, just as I am now.

It's no surprise that nearly four years later— after a Sunday post-matinee performance of her latest work, slip, in West Philadelphia’s stylish new yoga, meditation, and performance venue Studio 34— Foley would ask me to moderate a conversation between her audience, the dancers and herself. Without hesitation, I took the steering wheel of the post-performance discussion and put it in drive.

Luckily for me, I had launched a conversation with Foley about her new work more than a year ago when slip was a newborn, a tight 12-minute solo performed by Megan Bridge in Current, a performance showcase at Mascher Space Co-op. Current is an interdisciplinary platform curated by Zornitsa Stoyanova for performance artists to show their work and share new ideas. It was there, in a medium-sized loft on Cecil B. Moore Avenue, that I got my first glance at Meg Foley’s research.

Since then, slip has grown into a full-scale, evening-length work using the bodies of Philadelphia's finest female dancer/choreographers. Megan Bridge has continued with her part while Alison D’Amato, Devynn Emory, Erin Foreman-Murray, Michele Tantoco and Christina Zani have also joined the cast. They move inside the powerful electric sound environment of Josh Cicetti, around the set design of Mandy Carmichael and Matt Saunders, and against the lighting design of Kim Comer with text by Charlotte Ford and costume design by J. Makary and Meg Foley.

Too post-modern for pointe

With its soft couches and wooden coffee tables, Studio 34 reminds me of an immaculate living room where large windows admit immense amounts of sunlight. Filled with post-show excitement, we dancers sit there like little children waiting for Foley to recite a story. We acolytes presume that the choreographer of such a well-articulated performance would also be as articulate in her speech, fielding difficult questions with the grace of a ballerina. But of course Foley is a long stretch from performing with the Pennsylvania Ballet.

Her interest in movement is too post-modern for pointe. Instead she’s concerned with presence, community, spatial patterning and the complexity that dance forms create in perpetual motion. slip shifts and rocks against some euphoric and beautifully detailed tides of energy. As Foley puts it, “slip isn’t about anything finite. It is primarily about itself, about your and the dancers’ responsive bodily and emotional experiences of it. It is expressive and real and so holds all kinds of connotations and associations, but they are yours.”

That said, I certainly have more than a few associations and connotations. Because the audience is asked to walk throughout the space, we become part of the atmosphere; we are given the permission to create our own journey within the physical landscape of the dance.

Like seals mating

This process renders me just as aware of the pedestrian bodies in the space as I am aware of the dancers. At times the dancers move throughout the audience-created landscape; at others they create a landscape within and around their own bodies. They become seals mating; they become humans involved in a physical dialect; they become vessels transmitting kinesthetic information through geometric time. Foley is consistently redirecting the viewers’ attention. It’s as if I’m watching a game where transparent objects are thrown from one side of the room into the other.

But some questionable design elements about slip also come into focus. Why an all-female cast? Why slip as the title for this research? And why this movement exploration now?

slip began on the body of a woman, and Foley says she was interested in exploring the physical depth of the work solely among women. That feminist statement seems so exclusive. And then, near the end of the dance, a deep monotone male voice overshadows the work? I’m left thinking, “Here I am, within a society of women working inside a male-constructed sound environment where a huge column is placed dead center of the space specifically to obstruct my view.”

Are men the problem?

Foley contends during the discussion that she didn't want to create a dance about sisters or gender; this is quite simply the form the dance has taken. She insists that slip began as a working title that stayed; it's sufficiently open-ended to allow various implications to slip into view. But I can’t help wondering if these subconscious choreographic impulses are meant to imply that men overpower situations and obstruct sophisticated communication among women. Is this what they're teaching the women at Scripps College?

As a viewer and consistent dance-goer, I want to know what this piece is about. But I also understand that this need to know can obstruct the pure pleasure that comes from the simple act of watching bodies moving through space. “Open text” is how Foley describes her movement language, and isn’t that what any good piece of art does— opens up a discourse just enough for interpretation while being very detailed and crafted in its line of investigation?

I applaud Foley's work. Self-produced dance art is hard to create. Foley is a savvy young woman who’s showing relevant work in Philadelphia, and no matter how much I might want to label it, preserve it or impose a particular meaning onto it, essentially her dance is about dance.

As an educated audience member, I can accept that. I know I possess the ability to approach her work without assumption, expectation, association or connotation. I also know that if I want to truly see and acknowledge the most important thing about slip (and any other dance, for that matter), then I must first allow myself to find the sheer enjoyment that comes from the clear and present ritual of simply watching moving bodies perform.

An encounter with Meg Foley

"The desire to preserve and represent the performance event is a desire we should resist. For what one otherwise preserves is an illustrated corpse..."

-Peggy Phelan, from Mourning Sex: Performing Public Memories

JAAMIL OLAWALE KOSOKO

I first encountered the choreography of Meg Foley at an American Dance Festival Open Showing in Durham, NC. We were dance students from opposite ends of the nation. She was finishing her studies at Scripps College (an all women’s college in California) while I was beginning my senior thesis at Bennington College (a former all women’s college in Vermont). Although our performance esthetics were (and still are) quite different, I was drawn to her movement ideas then, just as I am now.

It's no surprise that nearly four years later— after a Sunday post-matinee performance of her latest work, slip, in West Philadelphia’s stylish new yoga, meditation, and performance venue Studio 34— Foley would ask me to moderate a conversation between her audience, the dancers and herself. Without hesitation, I took the steering wheel of the post-performance discussion and put it in drive.

Luckily for me, I had launched a conversation with Foley about her new work more than a year ago when slip was a newborn, a tight 12-minute solo performed by Megan Bridge in Current, a performance showcase at Mascher Space Co-op. Current is an interdisciplinary platform curated by Zornitsa Stoyanova for performance artists to show their work and share new ideas. It was there, in a medium-sized loft on Cecil B. Moore Avenue, that I got my first glance at Meg Foley’s research.

Since then, slip has grown into a full-scale, evening-length work using the bodies of Philadelphia's finest female dancer/choreographers. Megan Bridge has continued with her part while Alison D’Amato, Devynn Emory, Erin Foreman-Murray, Michele Tantoco and Christina Zani have also joined the cast. They move inside the powerful electric sound environment of Josh Cicetti, around the set design of Mandy Carmichael and Matt Saunders, and against the lighting design of Kim Comer with text by Charlotte Ford and costume design by J. Makary and Meg Foley.

Too post-modern for pointe

With its soft couches and wooden coffee tables, Studio 34 reminds me of an immaculate living room where large windows admit immense amounts of sunlight. Filled with post-show excitement, we dancers sit there like little children waiting for Foley to recite a story. We acolytes presume that the choreographer of such a well-articulated performance would also be as articulate in her speech, fielding difficult questions with the grace of a ballerina. But of course Foley is a long stretch from performing with the Pennsylvania Ballet.

Her interest in movement is too post-modern for pointe. Instead she’s concerned with presence, community, spatial patterning and the complexity that dance forms create in perpetual motion. slip shifts and rocks against some euphoric and beautifully detailed tides of energy. As Foley puts it, “slip isn’t about anything finite. It is primarily about itself, about your and the dancers’ responsive bodily and emotional experiences of it. It is expressive and real and so holds all kinds of connotations and associations, but they are yours.”

That said, I certainly have more than a few associations and connotations. Because the audience is asked to walk throughout the space, we become part of the atmosphere; we are given the permission to create our own journey within the physical landscape of the dance.

Like seals mating

This process renders me just as aware of the pedestrian bodies in the space as I am aware of the dancers. At times the dancers move throughout the audience-created landscape; at others they create a landscape within and around their own bodies. They become seals mating; they become humans involved in a physical dialect; they become vessels transmitting kinesthetic information through geometric time. Foley is consistently redirecting the viewers’ attention. It’s as if I’m watching a game where transparent objects are thrown from one side of the room into the other.

But some questionable design elements about slip also come into focus. Why an all-female cast? Why slip as the title for this research? And why this movement exploration now?

slip began on the body of a woman, and Foley says she was interested in exploring the physical depth of the work solely among women. That feminist statement seems so exclusive. And then, near the end of the dance, a deep monotone male voice overshadows the work? I’m left thinking, “Here I am, within a society of women working inside a male-constructed sound environment where a huge column is placed dead center of the space specifically to obstruct my view.”

Are men the problem?

Foley contends during the discussion that she didn't want to create a dance about sisters or gender; this is quite simply the form the dance has taken. She insists that slip began as a working title that stayed; it's sufficiently open-ended to allow various implications to slip into view. But I can’t help wondering if these subconscious choreographic impulses are meant to imply that men overpower situations and obstruct sophisticated communication among women. Is this what they're teaching the women at Scripps College?

As a viewer and consistent dance-goer, I want to know what this piece is about. But I also understand that this need to know can obstruct the pure pleasure that comes from the simple act of watching bodies moving through space. “Open text” is how Foley describes her movement language, and isn’t that what any good piece of art does— opens up a discourse just enough for interpretation while being very detailed and crafted in its line of investigation?

I applaud Foley's work. Self-produced dance art is hard to create. Foley is a savvy young woman who’s showing relevant work in Philadelphia, and no matter how much I might want to label it, preserve it or impose a particular meaning onto it, essentially her dance is about dance.

As an educated audience member, I can accept that. I know I possess the ability to approach her work without assumption, expectation, association or connotation. I also know that if I want to truly see and acknowledge the most important thing about slip (and any other dance, for that matter), then I must first allow myself to find the sheer enjoyment that comes from the clear and present ritual of simply watching moving bodies perform.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko