Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

FDR's getaway, and mine

Roosevelt's Hyde Park hideaway

Many critics debated the accuracy of Roger Michell's Hyde Park on Hudson even while they praised Bill Murray's impersonation of Franklin D. Roosevelt. So recently I revisited FDR's famous home north of New York City to see for myself.

I'd been to Hyde Park's main house and library before, as well as Eleanor Roosevelt's nearby retreat, the stucco-covered Val-Kill Cottage, where the first lady entertained whomever she wanted (or no one, if she chose).

But I knew nothing about Top Cottage, the more secluded hideaway that her husband designed and built, where much of the film's action takes place. (That's where, in 1939, Roosevelt served hot dogs and Virginia ham to Britain's King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on the historic first state visit to the United States by a British sovereign.)

I'm hardly alone in my ignorance. Each year 130,000 people visit the presidential mansion at Hyde Park; but only 55,000 visit the Eleanor Roosevelt cottage, and fewer than 4,000 visit Top Cottage.

Escaping wife and mother

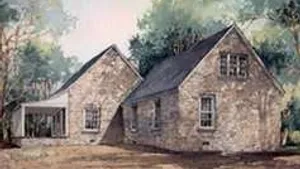

Top Cottage was designed to accommodate Roosevelt's need for wheelchair accessibility. (It was one of America's earliest handicapped-accessible buildings.) It's the only home designed by a U.S. president other than Thomas Jefferson, and the only one designed by a president while in office.

FDR envisioned the cottage as (in his words) "a small place to go to escape the mob"— by which he meant his overbearing mother, his wife and his retinue. It contained no telephone, as per his express directive. The film would have us believe that it also was a place where Roosevelt shared intimacies with his cousin, Daisy Suckley.

Consequently, Top Cottage is the most poignant and personal reminder of Roosevelt's private life.

Although cars can park adjacent to FDR's big mansion and Eleanor's retreat, Top Cottage is reached only by a National Park Service shuttle, which navigates a seven-mile twisting road before coming upon the small structure on the edge of the woods.

FDR's priorities vs. Dad's

It's built of fieldstone, which Roosevelt's workers retrieved from old walls in his fields. Its interior surfaces were bare plaster. I sat on the slate-floored porch where FDR greeted the British royal couple and discussed the destroyers-for-bases swap that came to be known as Lend-Lease. Three years later, on that same porch, FDR discussed war plans with Winston Churchill.

So you can imagine my surprise upon discovering that FDR's hideaway— the indulgence of a rich and powerful historic figure— shared much in common with my own middle-class childhood Philadelphia home. Both houses were built in the same year— 1938— and they share architectural elements that were unusual for that time.

FDR displayed no particular interest in modern art or architecture; his priority was accommodating his physical handicaps. On the other hand, my father (born in 1900) admired progressive, modern design. He found a willing collaborator in Maury Rose, a forward-thinking builder with an interesting idea for making money in the midst of the Great Depression.

Young, Jewish and upwardly mobile

In 1938 Rose acquired two blocks of empty lots on a tiny, not-fully-paved street in Philadelphia's Oak Lane section. He proceeded to custom design and build homes along that two-block stretch of Lawnton Avenue, including a home for himself that featured some art deco touches. His client/customers were youthful Jewish couples moving up from neighborhoods like West Philadelphia and Strawberry Mansion.

My parents— in their mid-30s and expecting their first child—fit the bill. They wanted to raise children in a suburban setting without leaving Philadelphia. Rose's "project" had no two homes alike, and most of them were more traditional in appearance than Rose's and ours.

I don't know how Rose got the money to invest, nor anything about his background. A Google search revealed nothing about him.

No peeking in

What I do see is a similarity in features. Both FDR's cottage and ours had simple lines and they had flat floors, without the raised sills that customarily divided rooms. Roosevelt made that decision so as to allow his wheelchair to roll easily, without bumps, from room to room.

Both FDR's cottage and our home used glass brick to allow light in, while blocking the view of anyone trying to peer in.

Roosevelt loved the idea of a home on a hilltop with a view of the Catskills, whereas my parents loved the 1937 Jerome Kern-Oscar Hammerstein song, The Folks Who Live On the Hill, whose lyric ran: "We'll build a home on a hilltop high, you and I."

Helicopter pad

To be sure, the two houses were hardly identical. FDR's cottage was a single story with a peaked roof. Ours was two stories and with a flat roof. (My future-minded father said the flat roof would accommodate our helicopter when those vehicles replaced automobiles.)

And FDR added a unique touch: All other windows were set low, so he could see through them from a seated position. All light switches were placed low enough for the president to reach. So were the bookshelves and kitchen appliances.

Of course there was no coordination between the plans for FDR's home and ours; the two dwellings were constructed simultaneously, with no knowledge of each other's existence. But both were the products of minds capable of thinking outside the box— and in some instances, I like to believe, both minds thought alike.♦

To read a review of Hyde Park On Hudson by David Woods, click here.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

I'd been to Hyde Park's main house and library before, as well as Eleanor Roosevelt's nearby retreat, the stucco-covered Val-Kill Cottage, where the first lady entertained whomever she wanted (or no one, if she chose).

But I knew nothing about Top Cottage, the more secluded hideaway that her husband designed and built, where much of the film's action takes place. (That's where, in 1939, Roosevelt served hot dogs and Virginia ham to Britain's King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on the historic first state visit to the United States by a British sovereign.)

I'm hardly alone in my ignorance. Each year 130,000 people visit the presidential mansion at Hyde Park; but only 55,000 visit the Eleanor Roosevelt cottage, and fewer than 4,000 visit Top Cottage.

Escaping wife and mother

Top Cottage was designed to accommodate Roosevelt's need for wheelchair accessibility. (It was one of America's earliest handicapped-accessible buildings.) It's the only home designed by a U.S. president other than Thomas Jefferson, and the only one designed by a president while in office.

FDR envisioned the cottage as (in his words) "a small place to go to escape the mob"— by which he meant his overbearing mother, his wife and his retinue. It contained no telephone, as per his express directive. The film would have us believe that it also was a place where Roosevelt shared intimacies with his cousin, Daisy Suckley.

Consequently, Top Cottage is the most poignant and personal reminder of Roosevelt's private life.

Although cars can park adjacent to FDR's big mansion and Eleanor's retreat, Top Cottage is reached only by a National Park Service shuttle, which navigates a seven-mile twisting road before coming upon the small structure on the edge of the woods.

FDR's priorities vs. Dad's

It's built of fieldstone, which Roosevelt's workers retrieved from old walls in his fields. Its interior surfaces were bare plaster. I sat on the slate-floored porch where FDR greeted the British royal couple and discussed the destroyers-for-bases swap that came to be known as Lend-Lease. Three years later, on that same porch, FDR discussed war plans with Winston Churchill.

So you can imagine my surprise upon discovering that FDR's hideaway— the indulgence of a rich and powerful historic figure— shared much in common with my own middle-class childhood Philadelphia home. Both houses were built in the same year— 1938— and they share architectural elements that were unusual for that time.

FDR displayed no particular interest in modern art or architecture; his priority was accommodating his physical handicaps. On the other hand, my father (born in 1900) admired progressive, modern design. He found a willing collaborator in Maury Rose, a forward-thinking builder with an interesting idea for making money in the midst of the Great Depression.

Young, Jewish and upwardly mobile

In 1938 Rose acquired two blocks of empty lots on a tiny, not-fully-paved street in Philadelphia's Oak Lane section. He proceeded to custom design and build homes along that two-block stretch of Lawnton Avenue, including a home for himself that featured some art deco touches. His client/customers were youthful Jewish couples moving up from neighborhoods like West Philadelphia and Strawberry Mansion.

My parents— in their mid-30s and expecting their first child—fit the bill. They wanted to raise children in a suburban setting without leaving Philadelphia. Rose's "project" had no two homes alike, and most of them were more traditional in appearance than Rose's and ours.

I don't know how Rose got the money to invest, nor anything about his background. A Google search revealed nothing about him.

No peeking in

What I do see is a similarity in features. Both FDR's cottage and ours had simple lines and they had flat floors, without the raised sills that customarily divided rooms. Roosevelt made that decision so as to allow his wheelchair to roll easily, without bumps, from room to room.

Both FDR's cottage and our home used glass brick to allow light in, while blocking the view of anyone trying to peer in.

Roosevelt loved the idea of a home on a hilltop with a view of the Catskills, whereas my parents loved the 1937 Jerome Kern-Oscar Hammerstein song, The Folks Who Live On the Hill, whose lyric ran: "We'll build a home on a hilltop high, you and I."

Helicopter pad

To be sure, the two houses were hardly identical. FDR's cottage was a single story with a peaked roof. Ours was two stories and with a flat roof. (My future-minded father said the flat roof would accommodate our helicopter when those vehicles replaced automobiles.)

And FDR added a unique touch: All other windows were set low, so he could see through them from a seated position. All light switches were placed low enough for the president to reach. So were the bookshelves and kitchen appliances.

Of course there was no coordination between the plans for FDR's home and ours; the two dwellings were constructed simultaneously, with no knowledge of each other's existence. But both were the products of minds capable of thinking outside the box— and in some instances, I like to believe, both minds thought alike.♦

To read a review of Hyde Park On Hudson by David Woods, click here.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

What, When, Where

Hyde Park on Hudson. A film directed by Roger Michell. Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site. Route 9 in Hyde Park, New York (about 85 miles north of New York City). (845) 229-9115 or www.nps.gov/hofr.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Steve Cohen

Steve Cohen