Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Creatures and things

Rilke, Rodin, and essence

At the end of my driveway on a rural road bordered on both sides by forest, I notice a dark mass in the middle of the road. When it begins to move, I discern it’s a turkey — oddly, only one turkey. Turkeys usually walk in flocks.

As the turkey moves slowly across the road, I can see that it is lamed, perhaps by a car or another animal, and abandoned by its flock to die. I experience the sight of this solitary lamed turkey differently than a bird within a flock. It speaks of being “not just a bird,” and yet not “not just a bird.” It reveals an existential dimension as a creature belonging nowhere.

For some reason, I think of this solitary turkey on a recent visit to the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. I read Rodin had a practice of cutting figures out of his drawings, thus isolating the figure from the ground. Through this isolation, the figure could be interpreted in different ways.

Destroying the ground

I imagine Rodin defiantly cutting into the drawings — removing figures, creating silhouettes without backgrounds. The defiance I imagine doesn’t consist of destroying the drawing but in destroying the ground, that ubiquitous context that imposes definition upon things. I wonder on what side Rodin might sit in the debate between an older Aristotelian metaphysics, in which things have essences, and contemporary thinking in which the very idea of essences is challenged, and things can only be understood by context.

As secretary to Rodin, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke learned to observe the world from the sculptor. He wrote, “[T]here is a silence; the silence which surrounds things.” For Rilke, things reveal their presence in this silence, leading to an inner reality that he refers to as essence. Things are spiritual force for Rilke. He wrote, “Things are violin bodies / Full of murmuring darkness.”

Charting unknown territory

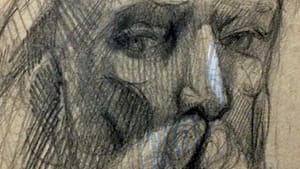

At the Rodin Museum, I find students drawin g the sculptures on pedestals that are surrounded by space. In this silent camaraderie, I, too, draw the figures.

g the sculptures on pedestals that are surrounded by space. In this silent camaraderie, I, too, draw the figures.

But drawing the figures presents a challenge, becoming an activity of charting unknown territory. The forms are human, yet different and unfamiliar. The figures will not be reduced to mere rendering of anatomical facts; instead they assume dimensions of their own. Philadelphia sculptor Kate Brockman later echoes this challenge of drawing Rodin’s sculptures, suggesting that they are “difficult to draw because the proportions are strange; surfaces are lumpy and unrefined — all the things that make a good Rodin.”

Gesture, not form

Despite my attempts, I find myself drawing the human form as I think it should be instead of what is visually presented to me in the sculpture; the magnet of conceptualized form is stronger than phenomenal form. But my struggle forces me to realize that Rodin wasn’t modeling human form — instead, he was modeling human gesture. This realization, in turn, makes me reconsider the use of the word essence in relation to Rilke.

Typically, essence consists of universal traits making a thing belong to a set, but to Rilke, essence seems to be quite the opposite. Paradoxically, essence becomes the ultimate nonessential — it refers to the singular; the creature. And when the word creature is traced to its etymological root — it is a thing created — it suggests a movement from nonbeing into being.

Creativity and context

I draw Rodin’s sculptures knowing that, like creatures, they can never be reduced to a set of traits, but are unique. This drawing brings forth another Rilke poem to mind; from a collection of his work, Possibility of Being, it begins “This is the creature there has never been.”

The creature in Rilke’s poem is “fed not with corn but with the possibility of being in an unpeopled space,” and I wonder about the relationship between creativity and context. Is creativity a function of context? If so, does creativity become predictable in its anchor to context? Or, does creativity to be truly creative need to transcend context, erupting like a lump on the surface of a Rodin sculpture — never to be predictable and never dependent upon a sum of circumstances, but becoming more than the sum? And if this is so, how does creativity find transcendence from context?

An unplanned gift

I’m not sure why, but I sent Possibility of Being to inmate Francisco Gonzalez, living for years, maybe decades, in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay State Prison. Francisco responded with a simple statement in penmanship so tiny and neat he could be the descendent of a monk scribe: “I want you to show me the ‘possibility of being.’ I could do it myself, but you have more experience. That is all.”

After a silence of two years, Francisco writes again; this time in larger, looser penmanship. No longer in solitary, he is enrolled in the prison college program, full of anticipation. He mentions the Rilke poem and its presence on his desk for two years. I like to think Rilke spoke in the quiet of the poem — a poem Rilke referred to as thing-poem — urging Francisco beyond the prison cell.

When I leave the Rodin Museum after a day of drawing, it is twilight and the dark Parkway trees are silhouettes against the sky suggesting another poem by Rilke:

Whoever you are: in the evening step out

of your room, where you know everything;

yours is the last house before the far-off:

whoever you are.

With your eyes, which in their weariness

barely free themselves from the worn-out threshold,

you lift very slowly one black tree

and place it against the sky: slender, alone.

And you have made the world. And it is huge

and like a word which grows ripe in silence.

And as your will seizes on its meaning,

tenderly your eyes let it go. . . .

When the turkey reaches the far side of the road, it disappears into the forest.

What, When, Where

The Rodin Museum. 2151 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. 215-763-8100 or rodinmuseum.org.

The second Saturday of each month, the museum hosts a drop-in sketching class; the next session will be on January 9, 2016. Information here.

Possibility of Being: A Selection of Poems by Rainer Maria Rilke. New Directions, 1977. Available at Amazon.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler