Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

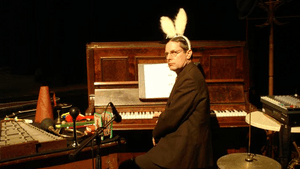

Relâche parties like it's 1899

Relâche season finale at the Penn Museum

In an exuberant performance, Really Old French Silent Films with Relâche Music Live! Relâche wrapped its 2015-2016 season with an afternoon of early film and music at Penn Museum.

Performing scores composed and/or arranged for the new music ensemble, Relâche accompanied four films by the prolific Georges Méliès (1861-1938), and the program’s highlight, the avant-garde classic “Entr’acte,” by René Clair (1898-1981). (Interestingly, “Entr’acte” comes from a larger work, Relâche, which inspired the ensemble’s name. The term is used on billboards to indicate “no performance.”)

"Entr’acte": stream of (un)consciousness

Made in 1924, when the Dada style challenged traditional artistic values in the wake of World War I, “Entr’acte” consists of silly unconnected scenes or, as Clair himself said, “visual babblings.”

A ballerina dances, but viewers see only the soles of the feet, legs, garters, and bloomers. (We saw a lot of those bloomers.) The ballerina is a man; eggs balance on spurting jets of water; we’re at the front of a rollercoaster as it swoops up, down, sideways, and backwards; there’s a funeral cortege: A hearse festooned with bread wreaths and large hams is pulled by a camel and followed by mourners. Suddenly, the hearse speeds up with mourners in hot pursuit, and we’re off on a chase that defies logic and physics. Eventually, the runaway hearse overturns, the casket tumbles to the ground, and its occupant emerges, very much alive.

“Entr’acte’s” lack of visual coherence places a lot of pressure on the score, composed by Erik Satie (1866-1925). Fortunately, Satie’s music, as arranged by Darin Kelly for Relâche, and performed by the ensemble, was up to the challenge. The accompaniment imposed just enough order to keep viewers connected to the scattershot visuals, enhancing their experience of the strange little film.

Méliès: prolific visionary

Georges Méliès brought magic to the more than 500 films he financed, directed, photographed, and starred in. He pioneered effects such as stop-motion, fading-in and –out, and dissolves to shift time and space.

Méliès’s subjects were as extraordinary as his technique. His best-known film, A Trip to the Moon (1902), follows villagers as they build and launch a rocket to the lunar surface. They camp out as comets speed past, and constellations rise in the night sky, each star with a smiling face at its center. They fight off aliens with umbrellas, and return to earth in a remarkably prophetic ocean splashdown. Similarly, The Impossible Voyage (1904) transports explorers to glaciers, the sun, and the bottom of the sea on a train outfitted with an ice tank and a submarine.

The scores, written and arranged for Relâche by composer and saxophonist Phillip Johnston (1955-), are part of Johnston’s larger Méliès Project, begun in 1997. Johnston’s melodies, deftly performed by Relâche, enhance the often-frenetic action.

It continues to be a revelation to see early film set to adapted and newly created music performed live. From the way the first films interpret the world, to the skill required to score them, to the enthusiasm of the performance, it is a treat to go back in time with Relâche.

What, When, Where

Really Old French Silent Films with Relâche Music Live! René Clair and Georges Méliès directed. June 12, 2016 at the Penn Museum, 3260 South St., Philadelphia. (215) 574-8248 or Relache.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.