Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The limits of science

'QED' revived at Lantern Theater

Richard Feynman (1918-1988) was a physicist and teacher associated with some of the most dramatic events of the last century — the creation of the atom bomb at the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, the development of quantum physics (“QED” refers to quantum electrodynamics, for which Feynman won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965), the panel investigating the Challenger disaster. He was also a man. And while it may seem daunting to create a play around a scientist and teacher, the current production of QED at the Lantern Theater Company transcends the science and reveals the man beneath the myth.

We meet Feynman (Peter DeLaurier) at a critical moment in his life. He has had cancer and surgery three times already, and now he must decide if he wants more or is willing to accept his fate. So he distracts himself with reminiscing, with planning a lecture on “What We Know,” with performing in a Caltech performance of South Pacific, and with almost seducing a young student enamored with both his ideas and the man himself.

He talks to the audience as if we are in the room with him. He tells us about a planned trip to Tannu Tuva, a republic in the Soviet Union, a trip that never took place. “Is hope an illusion to keep us moving?” he asks, still hoping to make the trip. A phone call interrupts, and he tells us to wait a minute, he’ll be right back with us.

As he talks, he lets us see his emotions. This is not the cold scientist so caught up in facts and figures he can’t relate to others; this is a man who enjoys life as much as he enjoys science. And a man who’s known pain. The death of his first wife Arline from tuberculosis. The realization of just what they created at Los Alamos.

Facing an insoluble problem

While Feynman has solved so many problems theoretically, now he’s confronted with a problem he can’t solve, the outcome of which cannot be known. Should he have surgery again or not? Should he try alternative treatments like radiation and interferon? What will be the result of any of these choices? Like the frozen O-ring that destroyed a space shuttle, he seems to be asking, how could something so small, like a tumor, bring down something so big, like a life?

The question harks back to Ezekiel Emanuel’s recent article, “Why I Hope to Die at 75” in The Atlantic, in which he talks about how aggressively he would attempt to prolong his life. Feynman in the play is not 75 — he died at age 69 in 1988 — and he had already been diagnosed with two forms of cancer (liposarcoma and Waldenström's macroglobulinemia), so it’s an immediate decision, not a theoretical one. It’s a question that’s still relevant today.

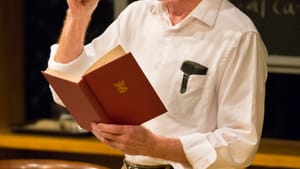

Watching DeLaurier as Feynman is not like watching an actor play a part — it is like watching Feynman himself give us a short course in theoretical physics with many digressions. “Is a photon a particle or a wave?” he asks. The answer doesn’t really matter to the audience, but his enthusiasm for science convinces us that it’s important to him.

A too-easy catalyst

When overeager Miriam Field (Clare Mahoney) enters the scene, it seems for a moment as if this play might go into Oleanna territory: the attractive young student, the admired professor, the potential for crossing lines. Fortunately it did not. However, this character seemed an odd intrusion into the play. Miriam provides Feynman with a reminder that life is still to be lived, but the character doesn’t really add anything new to the discussion. As the catalyst for his ultimate decision, she seems too easy a solution to a much more difficult problem.

The set was a perhaps too neat professor’s office. The props — tape recorder, answering machine — were reminders of the state-of-the-art technology of the time, along with the inevitable blackboard. But it was DeLaurier’s presence that filled the stage, and had it been a black box with a spotlight it would have worked just as well.

The play was based on Feynman’s writings, and there were mini lessons on physics that didn’t need to be grasped to enjoy the play. Ultimately, it is a play about resilience and how we get through hard times by distracting ourselves with life. “After Hiroshima, people still write symphonies,” Feynman says in wonder.

For Gary Day's review of QED, click here.

What, When, Where

QED. By Peter Parnell; inspired by Richard Feynman's writings and Ralph Leighton’s Tuva or Bust! M. Craig Getting directed. Through December 14, 2014 at the Lantern Theater Company at St. Stephen’s Theater, 10th & Ludlow Streets, Philadelphia. 215-829-0395 or www.lanterntheater.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Naomi Orwin

Naomi Orwin