'Don Quixote': Precious original, perfect copies

Piffaro, the Renaissance Band, presents 'The Musical World of Don Quixote'

For a 400-year-old classic, Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote sure is modern. It’s as packed with pop cultural references as something by David Foster Wallace or Dave Eggers, albeit the pop culture of the 1600s. Don Quixote is full of allusions to politics, books, plays, and music — lots of music — that would have been completely familiar to its first readers.

This fall, Piffaro, the Renaissance Band, along with partner cultural institutions, offers a special chance to experience one of the world’s greatest books through the eyes and ears of its first audience. The Musical World of Don Quixote is coming to life in Philadelphia, thanks to Philadelphia’s rich holdings in treasures of the Spanish Golden Age and the artistry of Piffaro, among the country’s preeminent period music performers. This project has been supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage.

"Somewhere in La Mancha..."

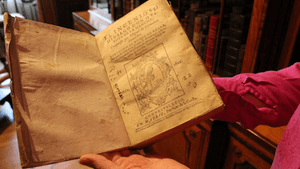

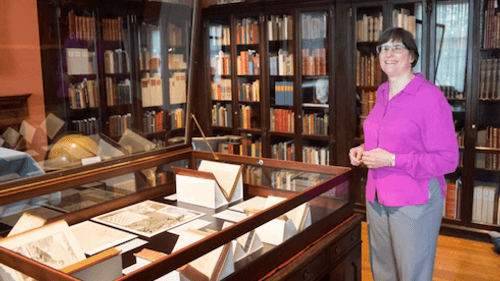

I’m at the Rosenbach Museum and Library, on Delancey Street. They’re displaying selections from their superb collection of Cervantiana for the festival. Librarian Elizabeth Fuller is leafing through their precious first edition of Don Quixote, Part I, dated 1605. She shows me the famous opening,

“En un lugar de la Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo…[Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago…]."

I can hardly believe she’s turning the pages (although the Rosenbach encourages touching — see the box for Hands On Tours). Don Quixote’s first edition is one of the rarest books in the world, hovering around number seven on “Rarest Book” lists, with the Gutenberg Bible at #1. The Rosenbach’s is one of only 18 copies of the first edition surviving after 411 years.

For a precious object, though, it’s surprisingly inviting. It’s solid, nothing fancy, readable, sturdy, about the size and heft of a modern bestseller. I read it over Fuller’s shoulder. We look less like hushed art pilgrims than friends picking a title out for our next book club meeting.

That’s what you find out from spending time with the real thing, says Fuller. “You learn what the original producers intended the book to be like,” she says, “who they thought the readers were going to be, how they thought readers were going to use it.”

To Fuller’s practiced eye, publisher and author had every intention of producing a volume that could stand up to being bought, read, loved, lent, told out loud, and shared by as many people as possible.

Good call. Don Quixote went on to become one of the best-selling novels in history — some say the best, the all-time blockbuster. An estimated 500 million copies to date have been sold, in editions ranging from cheap to deluxe with everything in between.

Joseph Shemtov, Librarian of The Rare Book Department of the Free Library, Central Branch, chose a number of very different presentations of Don Quixote to display for the festival. Among them are a famous 1780 Spanish edition from printer Joaquin Ibarra considered by aficionados to be an 18th-century masterpiece; the classic mid-1860s English/French edition with iconic illustrations by Gustav Doré; and a very early American version for children from 1823 with cartoon-y pictures included in a fold-out panel.

“We love having all these wonderful Don Quixotes on view for the show,” says Shannon Cline, Piffaro’s Executive Director. “It makes us feel part of such a great tradition, bringing this story to audiences for centuries.”

Everything old is new again

When Piffaro plays their version of Don Quixote in October, audiences will hear a lot of the original music from its pages for the first time in almost 400 years. Piffaro, the Renaissance Band, specializes in music of Cervantes’s times played on shawms, dulcians, pipes and recorders, the authentic instruments of the era. But this is something that’s only been possible very recently.

Piffaro’s instruments are authentic, but in fact they’re not old at all. They’re new — sometimes very new. For instance, one of bass dulcians Piffaro is playing this fall in The Musical World of Don Quixote was made 10 years ago by British master instrument-maker Eric Moulder in his workshop in Leek, Staffordshire (also home to a five-time world professional darts champion).

If the instruments were truly old, you wouldn’t want to hear them. Old woodwinds aren’t like violins, which improve with age. A centuries-old Stradivarius is incomparable; a centuries-old woodwind has issues. What professionals like Piffaro play are very fine, handcrafted replicas or reproductions of some of the few surviving original woodwinds.

Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, when interest in early music was growing, modern instrument makers started reviving the old crafts and bringing instruments back from extinction. Their expertise is constantly improving, and it’s a game changer. Musicians can finally do justice to a repertoire that has been silent for centuries. For Piffaro and early music, now is a second Golden Age.

During the festival, the Free Library’s Edwin A. Fleisher Collection, Central Branch, is displaying a selection of fine-crafted instruments borrowed from Piffaro — along with exhibits on Don Quixote’s legacy in music, curated by the Free Library’s Gina Bixler. QR codes are included in the display, too, allowing visitors to access audio while they look and get a real immersive experience in those glorious 16th-century sounds.

Why breathe?

Why look at old books; why listen to old music on old instruments, I ask Elizabeth Fuller at the Rosenbach. She thinks for a moment. I might have asked her, “Why breathe?” “Because they’re still good,” she answers. “Additions to the cultural world don’t negate what’s happened before. Bits from one era survive into others and inspire them.”

We look at the 1605 Don Quixote, lying on the table and inviting us to pick it up and read. That’s its job. Who knows how many people have found Don Quixote in its pages since that canny first buyer in 1605?

One of them is Mario Vargas Llosa, Fuller tells me. The writer stopped at the Rosenbach in 1994 after winning the Cervantes prize for Spanish literature in Madrid (he won the Nobel Prize in 2010). When Fuller brought out the 1605 Don Quixote, the old book sprang back into action as he opened it and read out loud, “En un lugar de la Mancha...[Somewhere in La Mancha…].”

“Mario Vargas Llosa,” says Fuller. “Oh my, oh my.” It’s a long, strong chain connecting four centuries of readers of all kinds and ways of life. And now it includes Piffaro and their beautiful new/old instruments, relinking their part of the story, making our modern world bigger and brighter by bringing the musical world of Don Quixote back into it.

Inspiring. Yes.

Editor's note: This article is the second in a series about Piffaro's work in progress, leading up to the October debut. The series is being presented on Broad Street Review in partnership with Piffaro.

To read the first article in this series, click here.

What, When, Where

The Musical World of Don Quixote. Piffaro, the Renaissance Band, with special guest artists New York Polyphony; Nell Snaidas (soprano, guitar); Glen Velez, percussion; Charlie Weaver (guitar, vihuela); Eric Schmalz (sackbut). October 8, 9, 2016 at the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral, 23 S. 38th St., Philadelphia, and symposium at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections. (215) 235-8469 or piffaro.org.

Additional 'Don Quixote' exhibitions:

Symposium: Music, Word and Art in the Age of Cervantes. Oct. 8, 2016 at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania, 34th and Walnut Sts., Philadelphia.

Ongoing at the Rosenbach Museum and Library of the Free Library of Philadelphia and the Free Library Fleisher Collection, both 2008 Delancey Place, Philadelphia.

Ongoing at the Free Library of Philadelphia Rare Book Department, Fleisher Collection, Parkway Central Branch, 1901 Vine St., Philadelphia.

Ongoing at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anne Schuster Hunter

Anne Schuster Hunter