Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Real and imagined crimes

'Philadelphia Noir,' edited by Carlin Romano

In considering Philadelphia Noir, our fair city’s recent contribution to short crime fiction, two elements should be noted. First, like the other volumes in Akashic’s city-centric “Noir” series, the stories included are neighborhood specific. Second, although all of the writers included in the volume are firmly tied to Philadelphia, and their editor is former long-time Inquirer critic Carlin Romano, no one involved in the project seems to have worked in law enforcement or crime. They’re all writers. Some are also journalists, some academics, and some can also write MFA after their names.

Thus, there are two implied evaluation methods for each story, beyond its merit as fiction. The first involves the question of fidelity to the quite specific place of a given tale, including characterization; the second measures the believability of the criminal activity as imagined by people who are professional imaginers.

Also, in his introduction, Romano asserts that “Philadelphia noir” doesn’t tend to be as glamorous as the noir stories of some other cities, or involve as many high profile characters as in Wall Street Noir or Los Angeles Noir: “In Philadelphia, we do ordinary noir — the humble killings, robberies, collars, cold cases that confront people largely occupied with getting by.”

So, the optimistic reader hopes for “everyday people” enmeshed in interesting or surprising crimes — with all involved in each story properly belonging in “the hood” specified.

A real Fallser

I started with the story set in my own neighborhood, East Falls. This story, Dennis Tafoya’s “Above the Imperial,” focuses on a very small-time criminal, Jimmy Kelly, a teen convict who once escaped from the locally infamous Youth Study Center on Henry Avenue, but didn’t even move out of the area. Jimmy certainly represents a certain type around my parts, but Tafoya manages to make the boy individual and sympathetic by infusing him with intelligence. For example, watching customers leave a local Chinese restaurant, Jimmy notes, “guys would walk out picking their teeth and patting their bellies, like it wasn’t enough to be full, you had to put on a play about it for your friends.”

However, the kid’s basically a dreamy kleptomaniac/stoner. He notes everything he steals in a composition book like the ones he used at St. Bridget’s, the neighborhood elementary school that closed in 2012. And with an opportunistic theft from drug dealers, he initiates a chain of events that causes a death, morally if not quite legally. The very end of this story is perhaps the best closing in the volume.

Literary choices

Other stories in the anthology are of similar quality, and most writers are careful with details about locale, as is Tafoya. But occasionally there’s a puzzling or too “literary” touch that might have been reconsidered by the writers involved. Aimee LaBrie’s South Philly story, “Princess,” for example, is a fine piece slightly marred by such a touch, but Keith Gilman’s “Devil’s Pocket,” while getting high marks for accurately representing a gritty neighborhood, includes a character who too neatly matches his description as a martyr by another character who probably couldn’t spell the word if he were spotted m-a-r-t-y.

Some stories are effectively surprising, like Duane Swiercynski’s “Lonergan’s Girl,” set in a Frankford El car in 1924. It follows a girl with green eyes, a stick-up man with a most unusual weapon, and the girl’s would-be romantic savior. There’s even a story by an actual Biddle (Cordelia) descended from both Nicholas Biddle and a Drexel that, some slightly clichéd phrasing aside, captures the tourist-neighborhood mix of the Independence Hall area. (The tale is somewhat inaccurately designated as representing “Old City.”) Incidentally, this story seems to be more about a mad Biddle who’s a writer, based on the writer herself, than about an actual crime.

This is a collection that should have made some real money if the short story form weren’t a distant seventh to tweets as a contemporary literary genre. (Amazon is selling copies of the book for as little as a penny, and my local librarian told me the book hadn’t been checked out in nearly two years.)

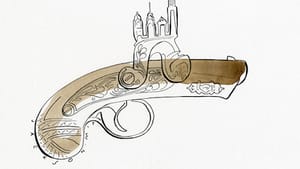

Most of the stories don’t quite capture the brutal pointlessness of some actual Philly crimes, but many of them ably demonstrate a truth of “ordinary noir” in real life: crime is capricious — that woman you don’t know has a famous name, the one who passes by you near the Second Bank of the United States? She may be nuts. And she may be packing a 19th-century Derringer.

What, When, Where

'Philadelphia Noir.' Edited by Carlin Romano. Published by Akashic Books, 2010. Available at Amazon.com for a price that’s a crime.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Rick Soisson

Rick Soisson

Illustration by Mike Jackson

Illustration by Mike Jackson