Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

What would Jesus do?

Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral and artist spar over 'Paul Cava/Inks'

Last Wednesday, February 14, West Philly's Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral was scheduled to open Paul Cava/Inks, a solo show of works by the Bala Cynwyd-based artist. Planning for the exhibition had been under way for months, and this would have been a major exhibition of his work.

Cava, an internationally renowned artist, has been active in the Philadelphia art community since 1976. Cathedral staff twice reviewed the images to be used in the show, which were framed and hung. Then, that morning, Cava announced on Facebook that the exhibition had been cancelled “due to censorship.”

Eye of the beholder

The next day, the Philadelphia Inquirer ran a story by Stephan Salisbury about the cancellation. According to the story, parishioners visiting the cathedral for Ash Wednesday services were uncomfortable with six of the works: one-third of the exhibition. The Very Rev. Judith A. Sullivan, dean of the cathedral, called Cava to ask him to remove them from the show following its opening reception.

Cava refused, feeling that their removal would violate the show’s integrity. The cathedral didn’t budge. The artist then broke the stalemate by withdrawing the exhibition. It will now open, in its entirety, on March 3, 2018, at Old City's Moderne Gallery.

Dean Sullivan assured me of the cathedral’s admiration for Cava’s art in an email on February 15, 2018, but she also took issue with Cava’s perspective. “This was not a simple matter of prohibiting nudity,” she wrote. “As Anglicans, we clearly understand the goodness of God's creation and that we are each made in the image of the Creator.”

She emphasized that the cathedral is neither a gallery nor a museum, but a sacred space and primarily a place of worship and prayer. “It was not a matter of ‘caving’ to the demands of a few parishioners. I concluded that the images were not appropriate, removed them, and then phoned the artist.”

Is it censorship?

Cava maintains that cathedral staff had access to, reviewed, and accepted without qualification all the work well in advance of the opening, then suddenly reversed their decision. He believes their action constitutes ex post facto censorship.

{photo_2}

“One very important issue, it being the basis for my claim of censorship, is that the images were provided to both the curator and to the dean on two occasions to review and approve,” Cava said. “If the dean didn’t bother to enlarge the JPEGs I provided, that is no excuse. . . . Given that context, I feel the artwork was censored." Citing the church's ongoing visual arts program, he adds, "The cathedral has to decide if they are going to have a serious legitimate art program or not. Art, real art, is not always comfortable. That’s the point: it’s disruptive at times."

I admit I was angry and frustrated at the clumsy handling of the situation (full disclosure: Cava is a longtime friend and I am Episcopalian), but I wouldn’t call it censorship. Whatever else an Episcopal cathedral might be, it is not a government body, and in these heady days of polarizing rhetoric, I’d count to 10 before calling their actions “suppression,” of nude images or anything else.

Governments censor; nongovernmental institutions sanitize for their own protection. And — I must report with a sigh — the supposed protection of children. “Cava said that a family with a young child objected to the work,” Salisbury reported. However, one might think the parlous state of Philadelphia public schools or the Parkland massacre deserve more disapproval from concerned parents than six naked ladies on a church wall.

Drawn and quartered

Both art and religion share the aspiration of inspiring awe in contemplation of the human and the divine. The show’s structure illustrates that we are often kept from recognizing the divine in the human, and vice versa, by our own corruptions.

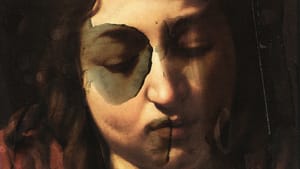

Inks is organized into four distinct parts. First, viewers see photographs of Khmer Rouge victims’ faces, taken from the archive of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Next, a series of photo collages of male and female bodies are bisected, trisected, and overlaid, one upon the other. The third section features manipulated images of female nudes by photographer Jeanloup Sieff. The fourth and final section includes a series of pages torn from a book of reproductions of Old Masters' paintings of Christ.

Cava stained or overlaid each of these with black, white, and gold inks. In some, the effect distorts, obscures, or darkens the underlying image of faces or bodies. In others, the stains produce bursts of white that leap from the gray or brown photographs. The stains stand in for our own preconceptions of the human body’s vulnerability.

The images are of perpetrators, victims, objects of political violence, objects of desire, beings to be punished, hated, or loved. As the show closes with the Christ prints, we are reminded that the central figure of Christianity was himself the victim of political violence, as vulnerable in his physical body as we are in ours. This is a vulnerability to which all the show’s other images — Cambodian faces, male and female nudes — equally attest.

"Love better than wine"

Obviously, whether one calls the cathedral’s decision censorship or not, Cava’s work brought not peace but a sword. One of the messages of Matthew 10:34 is that Christ forces us to face and accept unpalatable and even objectionable truths. These will, at times, bring us into conflict with our own families, friends, and communities.

The cancellation of the show was the product not of ideological censorship but of Realpolitik, as common in the church as in any human organization. I would have hoped an Episcopal cathedral would keep its word to an artist, whether a parishioner or not, and refuse to cave in to perceptions that belie their own puritanical, censorious strains.

But there you have it. Dean Sullivan denies she caved to that sentiment, but given the chain of events, Salisbury’s report, and her own admission that the images were “too sensual in the judgment of some,” it’s hard to conclude otherwise. After all, images don’t suddenly become more sensual on their own.

Even the Bible has room for the Song of Songs, a celebration of erotic love and other things besides. It reminds us that sensuality, like the body, is a gift of God.

What, When, Where

Paul Cava/Inks. March 4 to April 14, 2018, at the Moderne Gallery, 111 N. Third Street, Philadelphia. (215) 923-8536 or modernegallery.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

George Hunka

George Hunka