Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Three to think on

Pennsylvania Ballet presents 'On Edge'

In a prelude discussion before the Pennsylvania Ballet’s On Edge, dancer Nayara Lopes talked about the challenge of preparing three very different contemporary pieces while at the same time preparing the classic The Sleeping Beauty. The audience, too, faced a challenge with these new pieces.

Marius Petipa created The Sleeping Beauty for wealthy patrons, who often provided the jewels ballerinas wore. Generations of edits have not erased that basic exchange. As an audience, we sit back and admire the rich panoply set before us. On Edge, however, demands our active participation, with minds and emotions fully engaged.

Power and passion

“TILT,” a world premiere choreographed by Helen Pickett to Philip Glass’s Concerto No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra and Partita for Solo Violin, was my favorite of the night. The program notes say that the book Architectural Body, by Madeline Gins and Shusaku Arakawa, inspired Pickett, but there seems nothing architectural about this flowing, passionate piece.

The answer lies in a quote from the book’s foreword, which counters philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s assertion that “the value of the world must lie outside of the world” with “a complexity of within rather than beyond.” “TILT” takes a deep dive within, and takes us with it.

The dance opens with a bright spotlight on a monumental set piece by Emma Kingsbury, a plinth with a stele rising at one end like the last standing wall of a building, with two large stones leaning precariously against it. The program notes say it’s a cross-section of the earth, but it speaks of civilization lost, of Stonehenge. Two dancers appear, and suddenly, more dancers rise from the darkened floor; the stage teems with life.

Emma Kingsbury’s costumes, flowing skirts of different lengths in blues, greens, and yellows, and shorts and flowing wraps for the men, together with the set piece, take us out of the present into a more primal time we carry within us.

Glass’s music is a throbbing pulse that animates the dancers, trios, pairs, and the ensemble, always in connection. They’re eye to eye, in challenge or passion, building in intensity until scarcely contained. In the background, on the other side of the henge-world, dancers bathed in red light wait and watch.

A highlight of the performance was a pas de deux with Mayara Pineiro and Sterling Baca. We expect extensions and technique, but their melting passion drew me into their connection. Pineiro’s compelling solo, at the center of the dancers seated around her, made me wonder: was she high priestess or sacrifice? Later, Oksana Maslova, dancing with Arian Molina Soca, moved me with a single gesture. At the height of a lift, she brought her arm down in a move that stroked her face: sorrow, maybe? That was the genius of this piece. I wasn’t sure what I felt, but it gutted me anyway.

The modern world

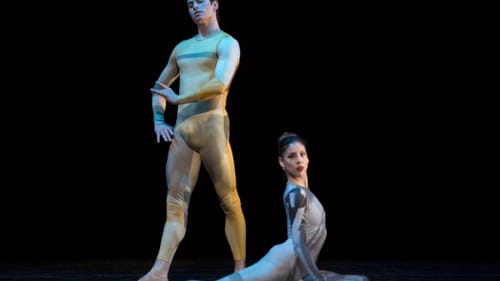

If “TILT” showed the power of the id, Matthew Neenan’s “It Goes That Way,” another world premiere, offered the superego. Set to songs by Laurie Anderson (“O, Superman,” “Violin Walk,” “It Tango,” “The Lake,” “Here With You,” and “From the Air”) and with futuristic unitards by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung, the dance was the quirky antithesis of Pickett.

Leavened with flashes of connection, this dance seemed to say that the more technology connects us, the more separated from each other we become. Arms swing like metronomes to the tick-tock of the soundtrack, and dancers in tight formation march like automatons with short steps and flexing knees. Albert Gordon stood out, whether wandering unseen through the other dancers or in a solo in which even the simplest move — sitting onstage, tapping his feet on the floor — was riveting.

Back to school

Just when I thought my brain would explode, choreographer Alexander Ekman went back to the last day of school. “Episode 31,” with costumes and makeup by Luke Simcock (courtesy of the Joffrey Ballet) and music by Mikael Karlsson, Ane Brun, and Erik Satie, was created for the graduation performance at Juilliard and retains the jubilation of such a celebration.

“Episode 31” begins with film, black and white in the rehearsal hall, where dancers talk about community and the new vocabulary of the dance. Then, like The Wizard of Oz, the dance explodes in color onto Broad Street, the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the subway. All around the city people watch, bemused, as a horde of youthful dancers in street clothes invade their space, even twerking in a wedding photo shoot. My favorite was a delighted small boy who danced and shouted along.

We were primed for a good time when the dancers appeared onstage in various bits of men’s formal wear, including gaiters holding up their socks, and fake mustaches on everyone. The curtain rose and fell several times, like a strobe at a dance party, and that is what it felt like — a joyous graduation party, dancers shouting as they danced while, in a professorial blue suit, James Ihde slowly paced his way across the stage.

What, When, Where

On Edge. "TILT," choreographed by Helen Pickett; "It Goes That Way," choreographed by Matthew Neenan; "Episode 31," choreographed by Alexander Ekman. The Pennsylvania Ballet. November 9-12, 2017, at the Merriam Theater, 250 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 893-1999 or paballet.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Camille Bacon-Smith

Camille Bacon-Smith