Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

New millennium homage to a 20th-century master

Paul Strand at the Art Museum (first review)

Paul Strand’s photographs are icons of the 20th century. They represent the people and the world of that epoch in a universal human way. Although Strand was a Marxist, his large corpus of photographs are not primarily documentations of class struggle. Rather, they chronicle the photographer’s carefully composed and intimate moments with people, places, and things that take on special meaning from the details and understanding contained in them.

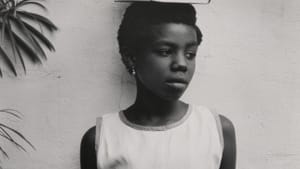

Some of Strand’s images are so embedded in our collective consciousness that they are as familiar to us as our own faces in a mirror. Think of his well-known photographs of Wall Street; of a white picket fence with rural buildings in the distance; of a woman beggar with her sign “Blind”; of a young man in Luzzara, Italy with an overwhelmingly intense expression; of a war bride in Maine; or of a confident, young African woman with books balanced securely on her head. They are by now recognizable parts of our world. In whatever he photographed, Strand captured something essential, something that we know to be true about ourselves.

The current exhibition of Strand’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is among the largest ever mounted. Amanda Bock, assistant curator at the Museum, told me that the current comprehensive exhibit includes 300 prints from over 4,000 that the Museum has acquired over time. Also on display are three documentary films; paintings by Strand, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Garfield Dove, and others; and examples of the actual cameras Strand used for both still and cinematic photography.

A powerful instinct for composition

What is remarkably consistent throughout Strand’s work is his unerring instinct for composition. With Strand, composition is never incidental, whether he achieves it by how he positions himself (as in the elevated camera location and oblique angle of the Wall Street photograph) or how he arranges his subjects (as in his still lifes and the careful placement of the family members in The Family, Luzzara, Italy, 1953) — or by the fortunate timing through which he clicks the shutter in the special moment (as in an early photograph of Central Park where someone “happens” to be walking just above the angled branch of a tree, creating an impression of a Japanese haiku painting). When you see the full corpus of work, you realize that Strand’s attention to composition never wavers and characterizes all of his work.

Strand was by conviction a socialist and a humanist with Marxist leanings. He is often regarded as having had such an agenda as a photographer — to document the struggles and dignity of the working class. He made two films, Redes (The Wave) and Native Land, which are clearly documents of social injustice and protest; the latter included avowed Communists in the production and cast. (Both are shown at the exhibit, along with the film, Manhatta, which he made early on with the artist/photographer Charles Sheeler.)

Aside from that, however, his photographic agenda was not about revolutionary ideology but about a fundamental humanism. His photographs each tell a story, the way a face or a tree branch tells a story, by the residue of its life in the eyes, the crevices, the turn of the lips. Strand gives to each subject, even objects and landscapes, a dignity and an eternal significance.

Capturing the dialectic

More than any other photographer, Strand captured in his work the dialectic between the camera as machine versus the subject as empathically understood. Strand was bound to the camera and dark room and used them as tools, technology, mechanical extensions of himself. On the advice of Steiglitz, he early abandoned photographic impressionism to take advantage of the unique capability of the camera to capture detail in sharp relief.

The camera as the medium is always palpable in his work. For example, in the photograph The White Fence, Port Kent, 1916, the depth of field and the light/dark contrast are crucial elements that juxtapose the clarity of the fence to the fuzzy mystery that occurs in the buildings in the distance. Everything is mediated by the camera lens. Yet, at the same time, with regard to his subjects, he “feels his way into” them in the manner that was described by the Romantic poet and philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder. He wants to “get inside” his subjects, yet at the same time he respects their inscrutability and privacy. His portraits exemplify what the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas called “Face,” the sense of responsibility that comes from one human being confronting another who demands ultimate responsibility and responsiveness.

The camera as the medium is always palpable in his work. For example, in the photograph The White Fence, Port Kent, 1916, the depth of field and the light/dark contrast are crucial elements that juxtapose the clarity of the fence to the fuzzy mystery that occurs in the buildings in the distance. Everything is mediated by the camera lens. Yet, at the same time, with regard to his subjects, he “feels his way into” them in the manner that was described by the Romantic poet and philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder. He wants to “get inside” his subjects, yet at the same time he respects their inscrutability and privacy. His portraits exemplify what the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas called “Face,” the sense of responsibility that comes from one human being confronting another who demands ultimate responsibility and responsiveness.

Unconcealment

Finally, one is touched by the patience and respect with which Strand’s photographs manifest Heidegger’s concept of “truth” as unconcealment. Heidegger said, “let beings be” and put forth a notion of artistic truth, alatheia, that harks back to Greek antiquity. For Strand, as for Heidegger, being discloses itself to someone who rightly relates to it. The subjects of Strand’s photographs gradually reveal themselves to the viewer over time. For example, I was looking for a long while at the “Blind Woman” photograph when suddenly I realized that above the striking “Blind” sign on her chest is a small, metal license, a commentary on bureaucratic blindness that strangely permitted the woman to legally beg.

The Strand exhibit is a magnificent homage and a distinct source of pride for the Museum and the city of Philadelphia. It will travel to museums in Switzerland, Spain, and England’s prestigious Victoria and Albert Museum. Those who take the time to view its many rooms will rediscover the sense of being human that is always endangered by war, poverty, bureaucracy, technology, hate, ignorance, and other forces that threaten our core identity.

For a review by Pamela J. Forsythe, click here.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

What, When, Where

Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography. Through January 4, 2015 at Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. 215-763-8100 or http://www.philamuseum.org/.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Victor L. Schermer

Victor L. Schermer