Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Is autobiography actually possible?

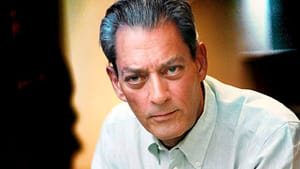

Paul Auster’s ‘Report from the Interior’

Paul Auster must be the most self-scrutinized author in America, excepting perhaps Philip Roth, who sprawled himself in various fictional guises across 31 novels and collections. Auster, preferring to speak more directly, has given us memoirs instead— five in all, with the last two, Winter Journal and Report from the Interior, conceived as a tandem covering much the same territory from different perspectives. Auster’s preoccupation, however, is not so much in giving an account of himself as of questioning whether such an account is possible: what it means to speak of a self, and a life.

Auster is now a celebrated writer, but he speaks little (and only in passing) of his years of success, only now and then dropping a reference that confirms that the young man he describes so obsessively has made it. It’s not, though, that Auster expects us to particularly care about him for that reason, for his very first prose book, The Invention of Solitude (1982), was likewise autobiographical. His interest is in the process of memory, that frayed rope by which the self— if there is a self— transports itself through time.

Excavating himself

When I read Winter Journal, I couldn’t help but be struck by how much Auster’s experience paralleled my own. We were both born in Brooklyn; both of us passed through many of the same social and political milestones; and both of us sought redemption, or at any rate refuge, from an America gone haywire by embracing a foreign culture. But I never possessed Auster’s power of recall for every address and every detail of furnishing he’d ever parked in (2, rue du Louvre, 1st Arrondissement; 29, rue Descartes, 5th Arrondissement, etc.). Nor, I must confess, did I harbor as interesting a skeleton in my closet as the fact that Auster’s grandmother had murdered his grandfather, the disclosure of which, he duly confesses, did not endear Auster to his family.

As this description may suggest, Winter Journal is a meticulously reconstructed account of the times and places Auster passed through from childhood on, recollected in less than tranquility on the verge of old age (Auster is 67). The lens is always turned outward, though the perspective is intensely personal: the world according to Paul. In Report from the Interior, “Paul” excavates himself, although, like someone prospecting in the dark, he cannot hope to give a full description of this particular habitation.

Both books are narrated in the second person, as if by an observant double who keeps encouraging Paul to be himself without any great expectation that this will be possible. As Auster notes in Winter Journal, the one thing one cannot accurately see is one’s own face; it is that which must be reported by others.

Panic attacks

Report from the Interior is largely taken up with Auster’s childhood — the time when one becomes convinced of having an identity, only to be most in doubt of it. “Every now and then,” Auster writes, “for no apparent reason, you would suddenly lose track of who you were. It was as if the being who inhabited your mind had turned into an impostor, or, more precisely, no one at all, and as you felt your selfhood dribble out of you, you would walk around in a state of stunned dissociation, not sure if it was yesterday or tomorrow, not sure if the world in front of you was real or a figment of someone else’s imagination.”

Auster doesn’t directly suggest it, but the panic attacks he suffered in adulthood might have had something to do with this “forgetting,” which is of course the naïve skepticism that can overwhelm us when the world is new and so much of what we’re told about it seems incompatible with our own inner experience. This was compounded, for Auster, by his discovery of the “invisibility” of being a Jew in America — that is, someone with a surplus identity that had no place or purpose in the culture to which he thought he belonged. In the 1950s, that was the way a young Jew grew up. It was also why, in the 1960s, so many young Jews became so violently disillusioned with that America.

Two films

Auster’s reconstruction of his childhood is the best thing about Report from the Interior. The next section, which he calls “Two Blows to the Head,” is a very curious pendant, an almost frame-by-frame recounting of two films the child Paul encountered: The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932). Both films involve the belittling of the hero, in the first case quite literally, and we can readily enough take the point that, for Paul, this was bound up with fears of invisibility and disappearance. Whether 70 pages are required to make it is another matter. It is true that film was an experience in early and mid-20th century America that no generation since has known, now that the big screen has been fitted into smaller and smaller ones. But prose, however discursively nostalgic, is no substitute.

Auster further undercuts his own story in the following section. As he goes back once again over his coming of age, he relates how a cache of old letters, long forgotten, had been returned to him by his first wife just as he was beginning to write Report from the Interior. Composing his new narrative on the basis of them, he is astonished to realize how faulty his memory has been and how different the Paul he has created for himself is from the young man he now finds. He thus finds himself in the position of being his own biographer, unearthing himself just as a third party would.

Undocumented life

So, is autobiography actually possible? Is the child Paul any more true to life than the misremembered young adult, fortuitously corrected? Report from the Interior ends with an album of photographs from the postwar era, none however personal: As Auster admits, virtually no picture or artifact from his childhood has survived, and his life, up to his 30s, is “the least documented of anyone you have known.”

If identity is a fable we tell ourselves, then what is it we represent to others? Auster leaves the question hanging. All we can reliably say of him, finally, is that he is a 67-year-old writer living in Brooklyn who has published such and so many books. Of whom can we say more?

What, When, Where

Report from the Interior. By Paul Auster. Henry Holt, 2013. 352 pages; $27. www.amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller