Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

PAFA's 'Art in Chicago'

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

"Bridges, South Chicago" by Herman Menzel is the first work you will enter en route to the exhibition proper. It was painted in 1937 and is very much a work of its time. It's a sort of heroic version of Regionalism that celebrates the people and their accomplishments. This is a moody nocturne, all brownish-red skies and gray-green river waters. It is very different from its neighbor, "LaSalle Street at Close of Day," painted by Alfred Juergens in 1915. Here we have Impressionism's last gasp, but the technique, though it has grown timeworn, is still capable of producing a lovely piece of visual reportage--you can almost hear the streetcars clanking. Realism is replaced by whimsy in Robert Amft's 1949 canvas "Along Michigan Avenue." Although this painting has fantastic qualities, it's really more of the jeu d'esprit in which viewers are invited to see how many Michigan Avenue landmarks they can identify. (A Legend block interprets your scores and avers that this is a genuine Robert Amft painting--closing with words that many a young artist would probably wish to copy: "If your favorite art dealer has no Amfts, demand that he stock them immediately.")

"Art in Chicago: Resisting Regionalism, Redefining Modernism" is a great big Norton Anthology of an art show that will introduce you to many fine artists you may never have heard of. In a way, it's a show whose title tells all. Chicago tried forging a Third Way. Rather than giving itself over wholeheartedly to modernism and abstraction, as New York City did it took what was best in its eyes. At the same time Chicago seems to have had a perfect horror of being viewed as "Peoria writ large." Thus, most of the art on view is representational art, but it has an edge to it. Interestingly enough, Chicago seems to have taken Surrealism to its heart in a way that New York never did.

This is a fairly large show, and it is organized along roughly chronological lines, according to the concept that innovation arrived on the Chicago art scene in waves. First came the fallout from New York City's big coming-out party for Modernism, the 1913 Armory Show, via a reduced touring version, which visited Chicago. Then came the World War II generation. Lastly there was a ’60s renaissance of sorts, as two small artists' co-ops reworked Pop Art, giving it a political and social edge that it had previously lacked.

This is the schematic of the show, but such schematics rarely do the art justice. To begin with, a certain amount of the art in the first wave clearly owed its aesthetics to the Modernism that preceded Modernism, by which I mean the great artistic upheaval of the fin-de-siecle period. Frederick Furtman's "Mazie under the Boughs" looks very like a poster for Stone & Kimball's The Chap Book. (This monthly in its day was the leading serious literary journal of the country and featured a typically Chicago blend of the revolutionary--Hardy, Yeats, and the first published translation of Mallarme's notoriously difficult Herodiade--and the traditional--Hamlin Garland and Ella Wheeler Wilcox.) Similarly, the hothouse eroticism of Leopold Seyffert's "Lacquer Screen" and Hodler-esque grandeur of Carl Hoeckner's "The Homecoming of 1918" would not have turned too many heads in 1900 Paris. There's even a "Salome" on display, painted by Macena Barton in 1936 and modern only in its stripped-down flatness.

Where the influence of the Armory Show does turn up--in the riot of colors and shapes that is Rudolph Weisenborn's "Untitled" and Manierre Dawson's "Fireman"--it becomes evident that abstraction, far from being a spiritual experience, was as much a visual vocabulary to be learned and applied as Impressionism had been. In fact, Weisenborn will turn up later on, painting in an entirely different visual style.

All good anthologies purport to present the subjects’ best, or at least most representative work; "Art in Chicago" is no different. Names that you never heard of become attached to images you are unlikely to forget. Frances Strain's "Life and Death in New Orleans" mixes Regionalism with Rousseau-esque naiveté; Charles White's charcoal portrait of the singer Leadbelly practically jumps off the wall. Julia Thecla's 1936 "Self-Portrait" is pure Magical Realism, while Aaron Bohrod's "Oakdale Avenue at Night" does a masterful job of combining Edward Hopper's "lonely town" rhetoric with Charles Burchfield's glittering strangeness.

The show’s second portion demonstrates just how creative an influence Surrealism wielded on the Chicago art scene. Ric Riccardo was both artist and successful Michigan Avenue restaurateur. He conceived a grand salute to "The Seven Lively Arts" by himself and six colleagues--Vincent D'Agostino, the brothers Ivan and Malvin Albright, Aaron Bohrod, William G. Schwartz and Rudolph Weisenborn—in which each artist depicted one of the arts. The results were both visually impressive and emotionally satisfying (a quality all too often ignored).

This is a good place to mention Ivan Albright--if, like me, you only knew his work from its appearance in the film, The Picture of Dorian Gray or from reproductions in journals or monographs, you owe it to yourself to visit the show just to see an Ivan Albright up close. Albright paints like Thecla on steroids, and his work is so alive with nervous energy that it pulls you toward it.

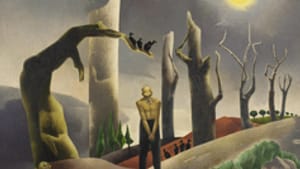

Before moving onto the concluding portion of the show, I would like to mention William G. Schwartz's other contribution, a stand-alone piece painted in 1947 called "De Profundis." The painting is done in a mildly stylized form of Realism that is all the more resonant for its being slightly strange-looking. The blasted landscape, the bowed half-naked figure being implored to by a skeletal arm emerging from the earth--these say all that need be said about the tragedies all too recently endured by Chicago and the world.

The concluding portion of the show brings us up to date with the works of many artists who are still alive and productive. Their revolution began in the 1960s and they drew their inspiration from Pop Art, but they have taken this largely apolitical movement and given it a bit of an edge. These artists, and indeed most of the artists in the show, were products of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and they bring a hip informed sensibility to their work. How can you not love artists who, instead of producing catalogs for their shows, draw comic books?

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.