Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Evolution/revolution in women's art

PAFA presents 'Graphic Women' and 'Beyond Boundaries: Feminine Forms'

Despite living in an era that provided little encouragement or approbation, women excelled in portraiture, illustration, printmaking, and watercolor from the 1880s to the 1930s. The evidence is on view in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ (PAFA's ) new exhibition, Graphic Women.

Containing etchings, pastels, pen-and-ink sketches, and watercolors from well- and lesser-known artists, the show traces movements in art through work produced by women, many with connections to PAFA. The school was historically one of the few supportive environments for female artists.

Scratching the surface

Etching, in which compositions are drawn with needles to create printing plates, experienced a U.S. revival in the late 1870s. Rather than focusing on mass-produced etchings, the exhibition spotlights small batches of press proofs, in which artists experiment with inks and papers. Two signed press proofs of Margaret M. Taylor’s The Berry Gatherers (1887) demonstrate the medium’s delicacy and detail.

In Taylor’s exquisite image, four girls outfitted with woven baskets and wide-brimmed hats roam knee-high through a berry patch. Before them, a small pond reflects spindly trees and high sky. Behind them are a dirt path and wooden gate, and in the distance, thatched-roof buildings and haystacks. Taylor creates a world of textures, from billowing dresses and glassy water to the solidity of tree trunks and wispy clouds.

Mary Nimmo Moran injects additional sparkle into a similarly pastoral scene, printing Gardiner’s Bay L.I., Seen from Fresh Pond (1881) on silk. It shimmers with ambient light, the appearance shifting as a viewer passes.

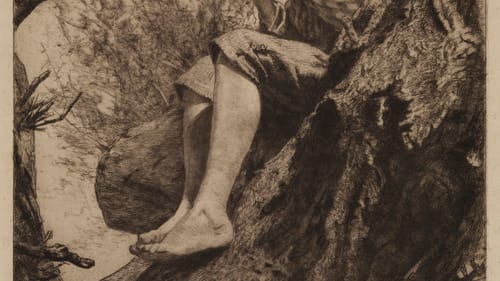

Willow Whistle (1888), by Ellen Day Hale, shows a barefoot boy perched in a tree, gently playing a hollowed-out twig. She printed the etching on buff paper, giving it a sepia tone that enhances its reflective mood. With nothing more than line and ink, she implies texture and, somehow, color: denim britches, fragile spring leaves, and the whistler’s thick red hair.

The usual suspects, and others

In Horses in a Park at Twilight (1880-1890), Hale employs charcoal to amazing effect, depicting a dusky cityscape, in which draft horses plod back to the stable. Streetlamps have just been lit and the driver, barely visible, has mounted the lead horse to guide him through the gathering dark.

A charcoal by Hale’s sister-in-law, Lilian Westcott Hale, uses the medium to opposite effect. In “The Veil” (1916), a bride sits at a window. Sunlight streams in, bleaching the space and revealing the filmy veil covering her from crown to elbow. Despite the scene’s whiteness, Hale shows us her pearls, the fan she clutches in her lap, and her despondent expression, hinting that this veil may not be her heart’s desire.

Well-known period artists are represented, including Mary Cassatt, Cecelia Beaux, and Violet Oakley. Viewers are reminded that Cassatt, identified with richly colored pastels, worked in varied media. Beaux, America’s leading female artist at the time, was PAFA’s first woman instructor and taught Oakley, who stars in a related exhibition at Woodmere Art Museum: A Grand Vision: Violet Oakley and the American Renaissance.

From making art to making a statement

Two pieces by Alice Barber Stephens nicely illustrate the evolution in art from a time in which a woman’s mere presence was a statement to one in which she spoke through the work. In Discussing the Stitch (1881), women sit shoulder-to-shoulder, leaning into needlework, a scene that discomforted no one.

Not so The Women’s Life Class (1879), which appeared in a Scribner’s Monthly article about PAFA. In it, Stephens shows female students sketching a nude female model — an experience for which they had to petition and which they did not achieve until 1868, long after their male counterparts. Hearth and home were no longer their only subjects.

One flight up, the story continues

In a serendipitous turn, a second PAFA exhibition reveals where these artistic ambitions led. In Beyond Boundaries: Feminine Forms, contemporary female artists charge ahead on the path forged by Beaux, Cassatt, the Hales, and others. The show might have been called Graphic Great-Granddaughters.

A dual-sited event at PAFA and Bryn Mawr College, this second exhibition examines “women’s art” as a genre and evaluates strategies for its continued relevance. The topics are as varied as the more than 70 artists represented, but many coalesce around barriers that continue to restrict and diminish women.

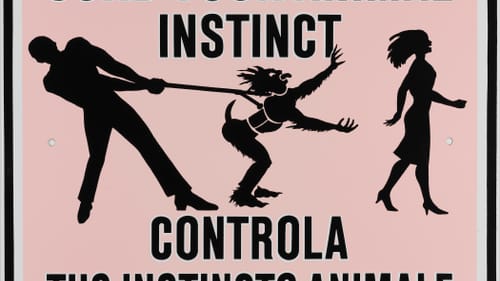

One work is particularly timely: Ilona Granet’s Curb Your Animal Instinct (1986), which borrows the style of Emily Post’s rules of etiquette to deliver a feminist message. Designed to resemble a traffic sign, it depicts in silhouette a man pulling a leashed beast away from a woman. It’s one of a series Granet created; the signs were posted in public spaces throughout New York City.

Given ongoing revelations of unchecked instincts, perhaps Granet’s signs can be mass-produced for posting in boardrooms, newsrooms, and government buildings. Though the format has changed from past generations, the message stays the same, as does the determination of the women delivering it.

What, When, Where

Graphic Women. Through February 18, 2018. Beyond Boundaries: Feminine Forms. Through March 18, 2018, both at the Historic Landmark Building, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 118-128 N. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 972-7600 or pafa.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.