Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

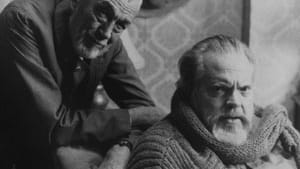

The best movie never made?

Orson Welles’s 'The Other Side of the Wind'

Orson Welles is to film directors what Marlon Brando is to actors: a figure of undoubted genius who bestrode his field for decades yet left the powerful sense of an unfinished legacy. Brando reinvented film acting with his performance in A Streetcar Named Desire, and then did it again 20 years later in Last Tango in Paris. In between, and after, there were not only flashes of intense brilliance and inventiveness, but also the sense of an actor at war with his profession and even his talent.

Orson Welles made an unparalleled directorial debut in Citizen Kane but never equaled it. He ran afoul of the studio system, finally went into self-imposed exile in Europe, and spent much of the last 15 years of his life trying to finance, film, and finish The Other Side of the Wind, the story of a gifted but mercurial director trying to stage a comeback at the age of 70. The film’s protagonist, Jake Hannaford, never completes his culminating masterwork. Neither did Welles, who died slumped over his typewriter, also aged 70.

Welles left behind more than 11 hours of footage in a Parisian editing facility, locked up in a tangle of legal and financial claims, including those of the Islamic Republic of Iran. People have been trying to gain access to the footage and complete the film for 30 years; confident plans to do so have just been announced (yet again) in the press. Of course, no realized version of it could be what Welles himself might have intended; he never allowed anyone to see the full script, and even that wouldn’t tell us much, because Welles kept making up and discarding things as he went along, and he frequently asked his actors to improvise. Nor can anyone imagine how Welles might have finally cut the film.

Coming in from the cold

The story of The Other Side of the Wind may thus be more fascinating than anything that will (or won’t) ever see the light of day in the work itself. It’s well told by Josh Karp in his Orson Welles’s Last Movie (St. Martin’s Press, 2015). Karp’s story begins in 1970 with Welles pitching his picture, which John Huston agreed to star in. Welles was trying to come in from the cold and make an American film for the first time in more than a decade. A legend in the business, he was a hero to a rising generation of independent directors who revered his work. Films like Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider had tapped into the ’60s counterculture; the monopolistic studio system had been broken for good; creative financing was the order of the day. What better moment for the scapegrace director of Citizen Kane to get his mojo back and outdo all the young kids?

Just as Welles was trying to sell The Other Side of the Wind to investors, the bad fairy showed up. Charles Higham was a young film scholar whose debut book, The Films of Orson Welles, while acknowledging Welles’s great gifts, charged him with having “a fear of completion” that had aborted many of his projects and ultimately betrayed his talents. Furious (and also anxious about the damage Higham’s book might do), Welles got a young acolyte, Peter Bogdanovich, to write a detailed refutation. For Karp, too, Higham was a villain. He was also, though, a fateful prophet. Not only was The Other Side of the Wind left unfinished and essentially unfinishable, but Welles’s erratic perfectionism also virtually ensured that this would be so.

Proving Higham’s point

It was not only a question of endless restarts and reshoots, of actors who visibly aged during the long years of off-again, on-again filming and were sometimes replaced. Welles’s compulsive editing, in which no shot or sequence was ever finally done, reached the point at which his subtleties were, as Karp concedes, lost on any eye but his own. It is in editing that a film is made, and no one had a better eye than Welles; there’s a passage in his Othello that creates what may be the most dazzling effect ever put on film. But endless refinement means ultimate incompletion. Money troubles slowed Welles; personal problems sidetracked him. It is possible, too, that a film whose subject was so close to his own career resisted closure. But the editing room swallowed him.

Lives were smashed, battered, or diverted in the giant wake of The Other Side of the Wind; Orson Welles was an expensive man to know. The story of his relationship with Bogdanovich — who made a breakthrough movie of his own, The Last Picture Show, while working for Welles — is particularly intriguing. Most fascinating though, is the partnership of Welles and Huston.

Like Welles himself, Huston was a maverick director and a man of outsized vitality and exorbitant tastes. There was no seeming clash of egos between them, however, and Huston, disciplined on the set if not necessarily off it, was generous with his own valuable time. Welles could have had no greater tribute to his own art than Huston’s patient collaboration and support over a good number of years, and one of the losses in The Other Side of the Wind is what, from the man who gave us Noah Cross in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, might have been an indelible performance.

Huston was a signal counterpoint to Welles in another way, though. He finished his own films, and though there were some potboilers to help pay the bills, he got his real work done from beginning to end, even at the last while tethered to an oxygen tank. Welles’s talent may have been the greater, but Huston left no one wondering what might have been. He even considered finishing Welles’s film after the latter’s death, but it was too late, and perhaps just as well. The John Huston version of The Other Side of the Wind might have been wonderful, but it would have been lacking one thing. It wouldn’t have been Orson Welles.

For the Indiegogo campaign endeavoring to raise $1 million to complete the film, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller