Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Creativity trumps monotony

Orchestra plays Beethoven's Fifth

The Philadelphia Orchestra's first subscription concert of the new year reminded me of the programs Eugene Ormandy used to schedule whenever he foisted a contemporary piece on the Orchestra audience. The concert combined a sure-fire attraction (Beethoven's Fifth) with the Orchestra's first performance of a modern piece (Michael Torke's Ash) and a rare performance of a relatively unfamiliar work from the early 20th Century: the British composer William Walton's 1929 Viola Concerto.

Ash is founded on a dark, heavily rhythmic string phrase that runs through most of its 15-minute length. Torke varies the theme now and then and embellishes it with bits for the winds, but I found the piece monotonous.

Walton's concerto, by contrast, is never monotonous. Walton understood the attractions of variety and possessed the creative imagination to supply it.

He also understood the soul of the viola. His first movement colors a gentle, beautiful viola line with an understated suggestion of longing and nostalgia. The second movement tries too hard to be exciting, but it's so short that its weaknesses can be overlooked.

The third movement returns to the mood of the first and ends with a few moving and unaccompanied notes from the soloist. Different members of the wind section accompany the viola as the concerto progresses, and all of them take on the viola's mood and personality.

Enlisted from the ranks

The soloist was the Orchestra's principal viola, Choong-Jin Chang. Presumably the Orchestra saves money by scheduling soloists taken from its own ranks, but this concerto normally features the principal viola in any case. Roberto Diaz, for example, played the solo role the last time the Orchestra played this concerto in 1999. Great violinists and cellists can pursue solo careers, but the masters of the viola's less flamboyant voice gravitate toward chamber groups and the first chairs in major orchestras.

Chang delivered the kind of performance many of us have heard him turn in when he appears with the city's smaller orchestras, with some beautifully nuanced solos.

I may be the only reviewer in musical history who has suggested that his local orchestra could play Beethoven's Fifth more often. As I've noted in the past, the Orchestra doesn't play the Fifth every season, and most subscribers only sign up for six concerts these days. So a typical Philadelphia Orchestra subscriber will encounter it about once every couple of years— only about 30 or 40 performances over a lifetime.

Nobody finds it odd if you watch Hamlet every couple of years. Or one of your favorite movies. So why should we feel people are stuck in a rut if they occasionally revisit 35 minutes of moving, highly varied music?

The Fifth's image problem

The Fifth suffers from an image problem created by all the hoopla surrounding its opening bars. Sometimes it seems that most of the liberal arts majors I know think the symphony consists of da-da-da-DUM over and over. Its popularity really rests on the excitement generated by the extended grand finale formed by its last two movements.

David Zinman has become a leading exponent of historically informed performances of Beethoven's work. (For a detailed discussion of this cultural controversy, see the first reader reviews of Zinman's 1999 recording of the nine symphonies on Amazon.) His Fifth is lighter and brisker than older interpretations, with an understated opening that avoids the portentousness the opening notes have acquired. The ending didn't thunder, but Zinman compensated with an overall clarity that highlighted Beethoven's incredible creativity.

Like most people, when I first started listening to music I responded to the force and grandeur of the worldview that Beethoven communicates. I still feel that's an important part of Beethoven's appeal. But nowadays I tend to focus on the way he keeps coming up with new melodies and new effects. No one has ever associated Beethoven with monotony.

Ash is founded on a dark, heavily rhythmic string phrase that runs through most of its 15-minute length. Torke varies the theme now and then and embellishes it with bits for the winds, but I found the piece monotonous.

Walton's concerto, by contrast, is never monotonous. Walton understood the attractions of variety and possessed the creative imagination to supply it.

He also understood the soul of the viola. His first movement colors a gentle, beautiful viola line with an understated suggestion of longing and nostalgia. The second movement tries too hard to be exciting, but it's so short that its weaknesses can be overlooked.

The third movement returns to the mood of the first and ends with a few moving and unaccompanied notes from the soloist. Different members of the wind section accompany the viola as the concerto progresses, and all of them take on the viola's mood and personality.

Enlisted from the ranks

The soloist was the Orchestra's principal viola, Choong-Jin Chang. Presumably the Orchestra saves money by scheduling soloists taken from its own ranks, but this concerto normally features the principal viola in any case. Roberto Diaz, for example, played the solo role the last time the Orchestra played this concerto in 1999. Great violinists and cellists can pursue solo careers, but the masters of the viola's less flamboyant voice gravitate toward chamber groups and the first chairs in major orchestras.

Chang delivered the kind of performance many of us have heard him turn in when he appears with the city's smaller orchestras, with some beautifully nuanced solos.

I may be the only reviewer in musical history who has suggested that his local orchestra could play Beethoven's Fifth more often. As I've noted in the past, the Orchestra doesn't play the Fifth every season, and most subscribers only sign up for six concerts these days. So a typical Philadelphia Orchestra subscriber will encounter it about once every couple of years— only about 30 or 40 performances over a lifetime.

Nobody finds it odd if you watch Hamlet every couple of years. Or one of your favorite movies. So why should we feel people are stuck in a rut if they occasionally revisit 35 minutes of moving, highly varied music?

The Fifth's image problem

The Fifth suffers from an image problem created by all the hoopla surrounding its opening bars. Sometimes it seems that most of the liberal arts majors I know think the symphony consists of da-da-da-DUM over and over. Its popularity really rests on the excitement generated by the extended grand finale formed by its last two movements.

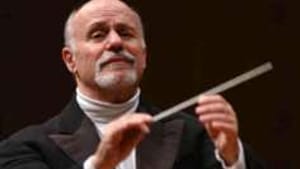

David Zinman has become a leading exponent of historically informed performances of Beethoven's work. (For a detailed discussion of this cultural controversy, see the first reader reviews of Zinman's 1999 recording of the nine symphonies on Amazon.) His Fifth is lighter and brisker than older interpretations, with an understated opening that avoids the portentousness the opening notes have acquired. The ending didn't thunder, but Zinman compensated with an overall clarity that highlighted Beethoven's incredible creativity.

Like most people, when I first started listening to music I responded to the force and grandeur of the worldview that Beethoven communicates. I still feel that's an important part of Beethoven's appeal. But nowadays I tend to focus on the way he keeps coming up with new melodies and new effects. No one has ever associated Beethoven with monotony.

What, When, Where

Philadelphia Orchestra: Torke, Ash; Walton, Viola Concerto; Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor. Choong-Jin Chang, viola; David Zinman, conductor. January 6, 2012 at Verizon Hall, Kimmel Center, Broad and Spruce Sts. (215) 893-1900 or www.philorch.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom