Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The surprising 20th Century

Orchestra 2001: Three composers, four soloists

When Orchestra 2001 arrived on the scene 20 years ago, James Freeman committed it to playing the music of the 20th Century. He has expanded that mandate to include the music of our new century, but he hasn't changed the most distinctive aspect of his organization's programming. Orchestra 2001 doesn't limit itself to avant-garde music. It plays the whole range of the music composed during the last 109 years— radical, conservative and moderate.

The ensemble ended its 2008-09 season with a program guaranteed to please most audiences: four attractive concertos featuring four first-class soloists.

David Finko is a composer who began his career as a military naval architect in the Soviet Union. When he was 35 he read the Bible for the first time and connected with his Jewish heritage. His Moses concerto is a response to his encounter with the central drama of the Old Testament.

A great epic in 20 minutes

In Finko's musical scheme, the brasses represent the voice of God, and the concerto opens with a fanfare worthy of the subject. The heart of the first movement is a dialogue between the soloist, who represents Moses, and a powerful, terrifying mystery. Finko didn't give the concerto a program, but it moves from tension to integration and ends with the orchestra and the two major voices advancing as a complex unity. Finko packs the essence of a great epic into 20 minutes of intense music. Marcantonio Barone played the virtuosic piano role with all the flair and understanding it requires.

Mimi Stillman delivered a hypnotic performance of a Vivaldi piccolo concerto when she soloed with Karl Middleman's Classical Symphony in 2007. Finko's 2006 piccolo concerto isn't that mesmerizing, but it has virtues of its own.

What's so funny about a piccolo?

The piccolo is a surprisingly sweet instrument. We expect it to shriek, but its greatest charm is its ability to produce long flights of pure melody. At the same time, there is something inherently comic about a piccolo solo. The piccolo is both winning and funny, and Finko exploits both aspects of its personality.

The opening section includes high showy passages and beautiful slow interludes played over a soft orchestra. The middle lento includes an aria that floats over pizzicato strings, and the final movement offers a bombastic, Soviet-style march on the strings with an appropriate response from the piccolo.

Finko's concerto could have benefited here from a slightly thinner orchestra. But the composer and the soloist both deserved the applause that greeted all three movements.

We don't normally applaud between movements these days, but audiences did it all the time well into the 19th Century. Nowadays Philadelphia audiences frequently applaud after the first movement of a concerto— an instinctive response to the showy cadenzas that end most first movements. Purists object that the applause mars the artistic unity of a piece, but a concerto like this one is partly a showcase for the soloist's talent and the composer's ability to write appealing music. Why wait to the end to let them know we're having a good time?

A classic genre for viola

The two pieces on the program's second half fell into the conservative to moderate category. Andrew Rudin's Concerto for Viola, Strings, Harp and Percussion fulfills all the expectations most of us bring to a viola concerto. For most of its length, the viola draws a flowing line that sings movingly above a variety of instrumental backgrounds.

Rudin does some creative things with the percussion section, but his concerto is essentially a perfectly realized contribution to a classic genre. Brett Deubner played his role with a full appreciation of the composer's aims.

Movie music

John Corigliano's Suite from The Red Violin belongs to a tradition that can be extended backward to the incidental theater music Purcell composed in the 17th Century and Mozart in the 18th. Modern pieces based on movie scores include monstrosities like the overblown, overlong Lord of the Rings carnival the Philadelphia Orchestra played at the Mann in 2004. But the roster also offers major works like Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kije Suite.

The Red Violin is a romantic film about violin music, and John Corigliano has succeeded in his stated aim. Corigliano's father was a solo violinist, and Corigliano has produced the kind of music "my father would have loved to play." He uses some unusual violin techniques here and there, but his suite is essentially a concerto "in the grand tradition."

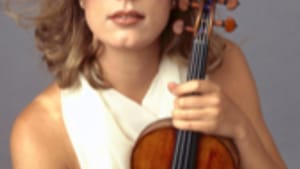

Elizabeth Pitcairn owns the Stradivarius chronicled in the movie, and she spends a large part of her time playing Corigliano's suite on the "red violin" itself. (Joshua Bell played the movie score.) Pitcairn has a few other items in her repertoire, so the suite isn't the only string on her bow. She displays all the technical skill the work requires, and she plays it with the unjaded enthusiasm of a performer who knows she's working with a winner.

The ensemble ended its 2008-09 season with a program guaranteed to please most audiences: four attractive concertos featuring four first-class soloists.

David Finko is a composer who began his career as a military naval architect in the Soviet Union. When he was 35 he read the Bible for the first time and connected with his Jewish heritage. His Moses concerto is a response to his encounter with the central drama of the Old Testament.

A great epic in 20 minutes

In Finko's musical scheme, the brasses represent the voice of God, and the concerto opens with a fanfare worthy of the subject. The heart of the first movement is a dialogue between the soloist, who represents Moses, and a powerful, terrifying mystery. Finko didn't give the concerto a program, but it moves from tension to integration and ends with the orchestra and the two major voices advancing as a complex unity. Finko packs the essence of a great epic into 20 minutes of intense music. Marcantonio Barone played the virtuosic piano role with all the flair and understanding it requires.

Mimi Stillman delivered a hypnotic performance of a Vivaldi piccolo concerto when she soloed with Karl Middleman's Classical Symphony in 2007. Finko's 2006 piccolo concerto isn't that mesmerizing, but it has virtues of its own.

What's so funny about a piccolo?

The piccolo is a surprisingly sweet instrument. We expect it to shriek, but its greatest charm is its ability to produce long flights of pure melody. At the same time, there is something inherently comic about a piccolo solo. The piccolo is both winning and funny, and Finko exploits both aspects of its personality.

The opening section includes high showy passages and beautiful slow interludes played over a soft orchestra. The middle lento includes an aria that floats over pizzicato strings, and the final movement offers a bombastic, Soviet-style march on the strings with an appropriate response from the piccolo.

Finko's concerto could have benefited here from a slightly thinner orchestra. But the composer and the soloist both deserved the applause that greeted all three movements.

We don't normally applaud between movements these days, but audiences did it all the time well into the 19th Century. Nowadays Philadelphia audiences frequently applaud after the first movement of a concerto— an instinctive response to the showy cadenzas that end most first movements. Purists object that the applause mars the artistic unity of a piece, but a concerto like this one is partly a showcase for the soloist's talent and the composer's ability to write appealing music. Why wait to the end to let them know we're having a good time?

A classic genre for viola

The two pieces on the program's second half fell into the conservative to moderate category. Andrew Rudin's Concerto for Viola, Strings, Harp and Percussion fulfills all the expectations most of us bring to a viola concerto. For most of its length, the viola draws a flowing line that sings movingly above a variety of instrumental backgrounds.

Rudin does some creative things with the percussion section, but his concerto is essentially a perfectly realized contribution to a classic genre. Brett Deubner played his role with a full appreciation of the composer's aims.

Movie music

John Corigliano's Suite from The Red Violin belongs to a tradition that can be extended backward to the incidental theater music Purcell composed in the 17th Century and Mozart in the 18th. Modern pieces based on movie scores include monstrosities like the overblown, overlong Lord of the Rings carnival the Philadelphia Orchestra played at the Mann in 2004. But the roster also offers major works like Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kije Suite.

The Red Violin is a romantic film about violin music, and John Corigliano has succeeded in his stated aim. Corigliano's father was a solo violinist, and Corigliano has produced the kind of music "my father would have loved to play." He uses some unusual violin techniques here and there, but his suite is essentially a concerto "in the grand tradition."

Elizabeth Pitcairn owns the Stradivarius chronicled in the movie, and she spends a large part of her time playing Corigliano's suite on the "red violin" itself. (Joshua Bell played the movie score.) Pitcairn has a few other items in her repertoire, so the suite isn't the only string on her bow. She displays all the technical skill the work requires, and she plays it with the unjaded enthusiasm of a performer who knows she's working with a winner.

What, When, Where

Orchestra 2001: Finko, Moses; Finko, Concerto for Piccolo and Orchestra; Rudin, Concerto for Viola, Strings, Harp, Piano and Percussion; Corigliano, Suite from The Red Violin. Marcantonio Barone, piano; Mimi Stillman, piccolo; Brent Deubner, viola; Elizabeth Pitcairn, violin; James Freeman, conductor. May 23, 2009 at Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center. (267) 687-6243 or www.orchestra2001.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom