Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The man behind the machines

NMAJH presents 'The Art of Rube Goldberg'

Rube Goldberg (1883-1970) has been an adjective in the dictionary longer than he was alive. The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) offers an opportunity to discover the man behind the descriptor in The Art of Rube Goldberg.

According to Merriam-Webster, which in 1928 added the name of the Pulitzer-Prize-winning cartoon illustrator to its lexicon, Rube Goldberg connotes an object or method that “accomplishes by complex means what seemingly could be done simply.”

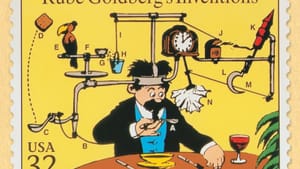

These objects or methods could include swatting a mosquito, finding soap in a bathtub full of water, or wiping your mouth with a napkin, which in Rube Goldberg terms requires a soup ladle, cracker, parrot, tiny bucket, scythe, bottle rocket, and clock, all linked together by a series of levers and strings. The Self-Operating Napkin was featured on a 1995 postage stamp honoring Goldberg, as well as in the Charlie Chaplin film Modern Times (1936).

Silly cartoons with serious points

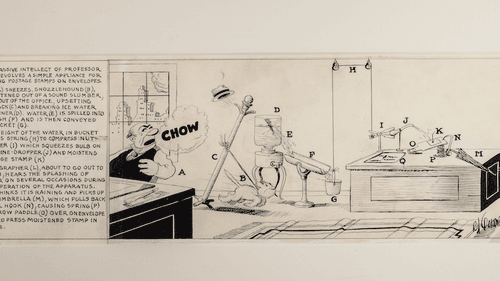

As demonstrated by his character Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, the machines became Goldberg’s best-known works, though they were only a sliver of his estimated 50,000 cartoons. “The machines are a symbol of man’s capacity for exerting maximum effort to achieve minimal results,” the artist said of the drawings, done in the style of U.S. patent diagrams.

“Crazy as some of my mechanical cartoons are,” Goldberg wrote in a 1923 essay in Popular Science, “most of them are mechanically possible.” Which would be expected, coming from a trained engineer. Goldberg earned a degree in engineering in 1904 at the University of California at Berkeley and worked in the field before leaving to become a cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle.

By 1915 he was nationally known, and over a 72-year-career the artist drew not only silly machines that commented on the irony of mechanization, but political cartoons and comic strips featuring "Foolish Questions" and a rogue’s gallery of characters, such as Boob and Bertha, Mike and Ike, and the Tuesday Ladies Club.

Influencing filmmakers, STEAM students

Goldberg’s granddaughter Jennifer George, who was instrumental in assembling the exhibition from the family’s trove of documents, drawings, and ephemera, believes cartoonist Art Spiegelman described her grandfather best when he said Goldberg “took readers from A to B using all the letters of the alphabet.”

As amusing as the inventions are on paper, they come alive on film, as in Soup to Nuts (1930), scripted by Goldberg and starring the Three Stooges. Modern filmmakers frequently pay homage to the technique: pop band OK Go’s video for “This Too Shall Pass” has more than 60 million views on YouTube

Generations who never saw the cartoons or heard the phrase in conversation know Rube Goldberg through Rube Works: The Official Rube Goldberg Invention Game, which challenges players to solve problems in Goldberg style on computers and mobile devices.

Or they may have participated in Rube Goldberg Machine Competitions (RGMC), which for 30 years have engaged science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) students.

Drawings crowded with detail and characters

But long before the games and contests, there were the meticulously constructed, richly drawn, and humorously scripted cartoons. In a Goldberg comic, a single frame may be divided into multiple centers of action; picture a party scene in a movie, in which the camera roams through the crowd, picking up individual vignettes.

Goldberg created many characters, differentiating class, occupation, ethnicity, and education through their shoes, the way their hair is combed, or how they talk. He used all of these elements to build larger points.

In If the Hat Doesn’t Fit It Isn’t Always the Hat’s Fault (1912), we see a man trying on a straw hat. The customer says, “It’s fair but there seems to be a slight declivity near the northwest corner of the left temple.” A salesman replies, “You ought to see a doctor — I’m only a hatter.” Characteristically, Goldberg includes multiple gags, including a lineup of men with oddly shaped crania across the bottom of the frame.

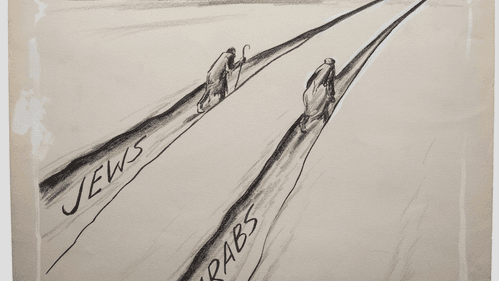

Larger messages with modern resonance

While the machine drawings could take Goldberg a week or more to design, he could draw two political cartoons in a day. One of these, a work on nuclear annihilation, Peace Today (1948), won Goldberg a Pulitzer Prize.

Another political image in the gallery is equally resonant for 21st-century visitors. The Great Upside-Down Philosopher (1950) shows Joseph Stalin holding a scroll on which a series of edicts are printed. These appear upside-down to the viewer: “Top is bottom. Black is white. Far is near and day is night. Big is little. High is low. Cold is hot and yes is no.”

George says she remembers the piece hanging in her grandparents' New York City apartment; as a child, she thought it was hung incorrectly because she had to stand on her head to read it. Not bad preparation for this time and place.

What, When, Where

The Art of Rube Goldberg. Through January 21, 2019, at the National Museum of American Jewish History, 101 S. Independence Mall East (Fifth and Market Streets), Philadelphia. (215) 923-3811 or nmajh.org.

NMAJH will host a Rube Goldberg Machine Competition December 9, 2018. Entrants will construct machines to deposit coins in piggy banks. Details at nmajh.org/rube.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.