Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

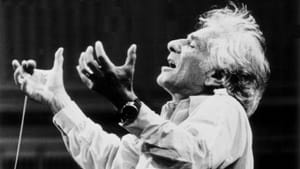

Artistry and activism

NMAJH presents 'Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music'

The synergy between Leonard Bernstein’s artistry and his activism gets a thorough examination at the National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music. Introducing Bernstein through letters, marked-up scores, recordings, treasured objects, and interviews, the exhibit, curated by Ivy Weingram of NMAJH, delves into what made Bernstein the musician and person he was.

The power of music depends on the passion of the composer. When that composer was Bernstein (1918-1990), the result was a beguiling statement against prejudice, ignorance, and hatred.

Shaped by sacred music

Bernstein had a Conservative Jewish upbringing in Lawrence, Massachusetts. There he was influenced by the liturgies and progressive music at Temple Mishkan Tefila. “I shall never… cease to be grateful for the power, conviction, and atmosphere with which [music] was conveyed,” he wrote in 1964. He was also a graduate of Philadelphia's Curtis Institute of Music.

Rather than eschewing his religious roots, Bernstein embraced them. In both sound and subject, Judaism echoes through his canon. A listening station allows visitors to sample orchestral and choral works such as Jeremiah (1942), Bernstein’s first symphony, which relates the story of the destruction of Jerusalem, and Kaddish (1963), his third symphony, which takes as its text the Jewish prayer for the dead. The latter was dedicated to the memory of President John F. Kennedy.

Faith influenced Bernstein’s popular works as well. The shofar is the first sound heard in his 1957 Broadway score for West Side Story. (The 1961 film score wafts through the gallery as excerpts play in a mini-theater.) And the comic operetta Candide (1956) contains a dance entitled “Old Lady’s Jewish Tango,” for which Bernstein prescribed a tempo he called “Hassidicamente.”

The meaning of the music

It’s a little like stepping into the maestro’s life: walking by possessions, reading his letters, watching interviews, and listening to his compositions. On view are Bernstein’s childhood piano, a gift from teacher Helen Coates; and a prayer book he always carried, in which he tucked a photo of his children. Items from his Fairfield, Connecticut studio include worn pencils for marking scores (red for musicians’ instructions, blue for conductor reminders), a well-rubbed mezuzah, and two battered touring trunks with much-mended handles.

The exhibit takes care to put Bernstein in context, sketching the social and political era that influenced him as a person and artist. He knew what it meant to be an outcast. He experienced anti-Semitism and was gay in a conforming, closeted age.

Bernstein did not live openly as a gay man until he and his wife, Chilean actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre, separated in 1976. He was acutely sensitive to the marginalized, and his sympathies were evident in the work he composed, the projects he selected, and the critical appearances he made.

In one of the exhibit’s films, he recalls being advised at the beginning of his career by the Boston Symphony’s Serge Koussevitzky to change his name. Koussevitzky had converted from Judaism to Russian Orthodox Christianity. The young conductor declined, saying, “I will have to make it as Bernstein or not at all.”

The exhibit enables visitors to assemble a timeline of important 20th-century moments, all of which correspond to Bernstein’s performance schedule. In Munich in 1948, he conducted an orchestra of Holocaust survivors. In 1967, soon after the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War, he led the Israel Philharmonic in Jerusalem. In 1985, he performed with a youth orchestra in Hiroshima to mark the 40th anniversary of that city’s bombing.

Scaling barriers of race, class

As the first American-born and -trained music director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein used his position to bring classical music to a wider audience. Excerpts are on view from the 1958-1972 Young People’s Concerts, which combined music with explanation in a relaxed, enjoyable format. Broadcast nationally on television, the series familiarized children (and many adults) with the classics.

Visitors can also read Bernstein’s bold 1947 New York Times commentary on racism in his profession, detailing obstacles faced by African Americans. A consistent advocate for civil rights, he later participated in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Raising awareness and suspicion

Bernstein’s outspokenness in paranoid times inevitably drew attention — his three-inch-thick, heavily redacted FBI file is on display. Though not blacklisted during the postwar Red Scare, Bernstein was affected, feeling it necessary in 1953 to sign an affidavit affirming he was not a Communist.

By 1971, when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis requested a new work for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Bernstein was still considered suspect. Advisors to President Richard Nixon advised Nixon not to attend the opening gala, fearing that MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers, with Bernstein’s music, Stephen Schwartz’s lyrics, and Alvin Ailey’s choreography, might contain hidden anarchist messages.

Nixonians need not have worried. Rather than hiding his radical beliefs, Bernstein put them on Broadway in 1944 in On the Town. The groundbreaking musical, with book and lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, featured a multiracial cast that held hands, portraying social equals onstage and sharing dressing rooms backstage.

Sono Osato, a Japanese-American ballerina, played the all-American beauty queen and Bernstein hired Everett Lee, an African-American violinist, to lead the pit orchestra.

“All my symphonies [are]…about the crisis in faith,” Bernstein explained in 1972. “I wouldn’t say that it’s God up there watching over me, as much as me down here looking up to find Him — I guess you could call that a chief concern of my life.” That search drove Bernstein to probe the depths and heights of human feeling, to leverage his artistry for just causes, and to use music to soothe, heal, and reconcile. Though Bernstein’s faith may have been in crisis, it was never in doubt.

What, When, Where

Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music. Through September 2, 2018, at the National Museum of American Jewish History, 101 S. Independence Mall East, Philadelphia. (215) 923-3811 or nmajh.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.