Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Man's hubris, atomic power and Fukushima's victims

Nakagawa's "Thousand Portraits of Hope' in New York

My approach to atomic energy in all its forms has always been simple: What begins in evil must end in disaster. So it has been for the people of Japan: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and now Fukushima, a third nuclear disaster, and one that's still unfolding.

The earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan on March 11, 2011 took its victims— 15,857 dead, 3,059 reported missing and 344,000 homeless as of April 2012— all at once. Japan suffers periodically from such calamities. But the catastrophic meltdown of the Fukushima reactors, caused by a tidal surge 30 feet above their protective barriers, was another matter.

The damage here, apart from the obvious site destruction itself, is invisible, insidious and in some respects incalculable. Everyone within a 12-mile zone was evacuated, but high levels of radioactivity were reported within a 30-mile radius.

Within these areas are ghost towns, slowly moldering away. Outside them is a large population that will never go home again. With limited government and foreign assistance, they have had in good part to fend for themselves.

God's destruction vs. man's

The Japanese-American artist Naoto Nakagawa , who has lived and worked in New York since 1962, decided to put a human face on these events. In eight self-funded trips to Japan, he undertook to sketch the thousand faces that now comprise his series, "Portraits of Hope." It's a remarkable historic document, and a no less remarkable work of art.

"Fukushima" is the generic name that has now attached itself to the general calamity that began with the greatest earthquake in Japanese history. Nakagawa, too, declines to distinguish among the victims of the earthquake, the tsunami and the nuclear cataclysm. But although in a literal sense these may all be regarded as aspects of a single event, there is obviously a profound bifurcation between its natural elements and those that were man-made.

Not much can be said about natural disasters; except for those who believe in a wrathful deity, they're the hazard of living on a volatile planet— probably the only kind of planet that could harbor life to begin with. Man-made disasters, on the other hand, take on a moral character. Their victims haven't merely been injured; in some sense they've been wronged.

Nakagawa's series joins a distinguished list of those who have recorded humanly inflicted disaster: Callot, Goya, Otto Dix and, most recently, Leon Golub and Fernando Botero. But these other artists have depicted war and torture. What happened at Fukushima was something different.

Good intentions

No one set out to deliberately injure anyone. The Tokyo Electric Power Company, which ran the Fukushima plant, and the Japanese government, which nominally supervised the nuclear industry, were guilty of laxity, negligence and misrepresenting data. These are faults, some of them possibly criminal, but none of them is a conspiracy to harm.

Yet moral culpability encompasses broader categories, as the ancient Greeks recognized. King Oedipus was guilty of hubris, even though he strove for justice and the public good.

The Japanese nuclear power industry, similarly, was concerned to deliver a public service— namely, reliable power at reasonable cost in a country that lacks fossil fuel resources. But it was also guilty of hubris. It believed— along with most Japanese opinion— that it could tame and domesticate the awful power that had not long before obliterated two of its cities.

How Japanese culture sought to convert the trauma and abjection of Hiroshima and Nagasaki into a sense of technological prowess, control and invulnerability— even in the face of evident contradiction— would require a far longer essay than this one. Why would anyone build a network of power plants, with the potential to render large portions of one's country uninhabitable for generations, on active earthquake faults? Does a more vivid definition of hubris exist?

(Of course, we Americans have the San Onofre plant in California sitting on the San Andreas Fault. Lucky so far.)

Lost identity

Nakagawa, however, isn't interested in apportioning blame but in recording suffering, loss and survivorship. His inspiration, as he explains, comes from the Japanese students who sent a thousand origami cranes— a traditional gesture of sympathy and support— to his son's school in New York after the 9/11 attacks.

When Nakagawa explained his own mission to contacts in Japan, he was introduced to the displaced population, many of whom had lost not only homes and family members but also all possessions, including photographs and memorabilia. Nakagawa was repeatedly told by his subjects that the drawings he had volunteered to make were the first personal images they had of themselves— the first material tokens of their actual existence.

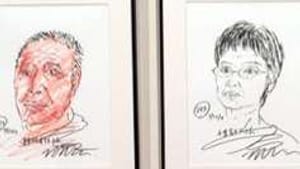

Nakagawa, who had never made portraits before, worked at great speed with pen and chalks. Astonishingly, each was made within five minutes— partly as a function of practical time constraints but, much more significantly, of artistic commitment and intensity.

"I just drew and drew whoever sat before me," Nakagawa told me. "Some of them cried, and I cried with them." Around them was "a war zone . . . a hell," with Japanese self-defense forces still digging for bodies and looking for further survivors. Again, the description is a morally charged one: For any Japanese to say "atomic disaster" is inevitably to invoke war.

Agony, and coping

What is the artistic result? The display of Nakagawa's work now on exhibit in New York consists of only 100 of his thousand images, but it's a representative sample, even if it can't convey the full force of the whole.

The first 160 to 170 portraits are highlighted with colored chalks— as Nakagawa explained, his emotive reaction to what he was depicting— but thereafter all are black-and-white, as if nothing extraneous need or should intrude on the seismographic record of what Nakagawa found before him in face after face.

Is this, then, a gallery of human agony? Yes and no: for these are people who have experienced devastation and irreparable loss, but they're also survivors— that is to say, people coping. Where Nakagawa finds visible traces of pain and trauma, he records them, but where he does not he imposes nothing. Trauma, indeed, often masquerades as calm, and understatement is the best access to it. So what one sees is the dignity and, more rarely, the pathos of ordinary people placed in the most appalling of circumstances.

Film or photography couldn't convey this. Only the unfiltered response of the artist's eye and the direct pressure of his hand, sustained but never distorted by compassion, produces that rarest of impressions: a sense of naked truth.

The artist's mother

Here we find people of all ages and walks of life, from infants to a centenarian. The first portrait is of Nakagawa's own mother, who urged him to fulfill his project. It's also the closest thing to a self-inscription, because the son's features are always visible in the mother's, and the sequence from the mother's gaze to the son's hand to the world observed is the artist's own encoded biography.

For this reason— for the deeply personal exchange that connects Nakagawa to his subjects— it's fitting that he entitles his suite "Portraits of Hope," and for this reason too that the last 70 images portray young children.

Nakagawa's portraits have also inspired photographs by Magdalena Solé of the devastated areas around Fukushima, and collages of damaged or destroyed photographs by Yoshihito and Saori Sasaguchi. These form a mute counterpoint to Nakagawa's images, as do the numerous poems contributed by ordinary citizens in response to the disaster, many of them published in Japanese newspapers and some reproduced here.

What will endure, however, is Nakagawa's suite. The faces he has recorded will, I believe, enter modern memory— as an ensemble and, in their vitally realized humanity, one by one.♦

To read responses, click here.

The earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan on March 11, 2011 took its victims— 15,857 dead, 3,059 reported missing and 344,000 homeless as of April 2012— all at once. Japan suffers periodically from such calamities. But the catastrophic meltdown of the Fukushima reactors, caused by a tidal surge 30 feet above their protective barriers, was another matter.

The damage here, apart from the obvious site destruction itself, is invisible, insidious and in some respects incalculable. Everyone within a 12-mile zone was evacuated, but high levels of radioactivity were reported within a 30-mile radius.

Within these areas are ghost towns, slowly moldering away. Outside them is a large population that will never go home again. With limited government and foreign assistance, they have had in good part to fend for themselves.

God's destruction vs. man's

The Japanese-American artist Naoto Nakagawa , who has lived and worked in New York since 1962, decided to put a human face on these events. In eight self-funded trips to Japan, he undertook to sketch the thousand faces that now comprise his series, "Portraits of Hope." It's a remarkable historic document, and a no less remarkable work of art.

"Fukushima" is the generic name that has now attached itself to the general calamity that began with the greatest earthquake in Japanese history. Nakagawa, too, declines to distinguish among the victims of the earthquake, the tsunami and the nuclear cataclysm. But although in a literal sense these may all be regarded as aspects of a single event, there is obviously a profound bifurcation between its natural elements and those that were man-made.

Not much can be said about natural disasters; except for those who believe in a wrathful deity, they're the hazard of living on a volatile planet— probably the only kind of planet that could harbor life to begin with. Man-made disasters, on the other hand, take on a moral character. Their victims haven't merely been injured; in some sense they've been wronged.

Nakagawa's series joins a distinguished list of those who have recorded humanly inflicted disaster: Callot, Goya, Otto Dix and, most recently, Leon Golub and Fernando Botero. But these other artists have depicted war and torture. What happened at Fukushima was something different.

Good intentions

No one set out to deliberately injure anyone. The Tokyo Electric Power Company, which ran the Fukushima plant, and the Japanese government, which nominally supervised the nuclear industry, were guilty of laxity, negligence and misrepresenting data. These are faults, some of them possibly criminal, but none of them is a conspiracy to harm.

Yet moral culpability encompasses broader categories, as the ancient Greeks recognized. King Oedipus was guilty of hubris, even though he strove for justice and the public good.

The Japanese nuclear power industry, similarly, was concerned to deliver a public service— namely, reliable power at reasonable cost in a country that lacks fossil fuel resources. But it was also guilty of hubris. It believed— along with most Japanese opinion— that it could tame and domesticate the awful power that had not long before obliterated two of its cities.

How Japanese culture sought to convert the trauma and abjection of Hiroshima and Nagasaki into a sense of technological prowess, control and invulnerability— even in the face of evident contradiction— would require a far longer essay than this one. Why would anyone build a network of power plants, with the potential to render large portions of one's country uninhabitable for generations, on active earthquake faults? Does a more vivid definition of hubris exist?

(Of course, we Americans have the San Onofre plant in California sitting on the San Andreas Fault. Lucky so far.)

Lost identity

Nakagawa, however, isn't interested in apportioning blame but in recording suffering, loss and survivorship. His inspiration, as he explains, comes from the Japanese students who sent a thousand origami cranes— a traditional gesture of sympathy and support— to his son's school in New York after the 9/11 attacks.

When Nakagawa explained his own mission to contacts in Japan, he was introduced to the displaced population, many of whom had lost not only homes and family members but also all possessions, including photographs and memorabilia. Nakagawa was repeatedly told by his subjects that the drawings he had volunteered to make were the first personal images they had of themselves— the first material tokens of their actual existence.

Nakagawa, who had never made portraits before, worked at great speed with pen and chalks. Astonishingly, each was made within five minutes— partly as a function of practical time constraints but, much more significantly, of artistic commitment and intensity.

"I just drew and drew whoever sat before me," Nakagawa told me. "Some of them cried, and I cried with them." Around them was "a war zone . . . a hell," with Japanese self-defense forces still digging for bodies and looking for further survivors. Again, the description is a morally charged one: For any Japanese to say "atomic disaster" is inevitably to invoke war.

Agony, and coping

What is the artistic result? The display of Nakagawa's work now on exhibit in New York consists of only 100 of his thousand images, but it's a representative sample, even if it can't convey the full force of the whole.

The first 160 to 170 portraits are highlighted with colored chalks— as Nakagawa explained, his emotive reaction to what he was depicting— but thereafter all are black-and-white, as if nothing extraneous need or should intrude on the seismographic record of what Nakagawa found before him in face after face.

Is this, then, a gallery of human agony? Yes and no: for these are people who have experienced devastation and irreparable loss, but they're also survivors— that is to say, people coping. Where Nakagawa finds visible traces of pain and trauma, he records them, but where he does not he imposes nothing. Trauma, indeed, often masquerades as calm, and understatement is the best access to it. So what one sees is the dignity and, more rarely, the pathos of ordinary people placed in the most appalling of circumstances.

Film or photography couldn't convey this. Only the unfiltered response of the artist's eye and the direct pressure of his hand, sustained but never distorted by compassion, produces that rarest of impressions: a sense of naked truth.

The artist's mother

Here we find people of all ages and walks of life, from infants to a centenarian. The first portrait is of Nakagawa's own mother, who urged him to fulfill his project. It's also the closest thing to a self-inscription, because the son's features are always visible in the mother's, and the sequence from the mother's gaze to the son's hand to the world observed is the artist's own encoded biography.

For this reason— for the deeply personal exchange that connects Nakagawa to his subjects— it's fitting that he entitles his suite "Portraits of Hope," and for this reason too that the last 70 images portray young children.

Nakagawa's portraits have also inspired photographs by Magdalena Solé of the devastated areas around Fukushima, and collages of damaged or destroyed photographs by Yoshihito and Saori Sasaguchi. These form a mute counterpoint to Nakagawa's images, as do the numerous poems contributed by ordinary citizens in response to the disaster, many of them published in Japanese newspapers and some reproduced here.

What will endure, however, is Nakagawa's suite. The faces he has recorded will, I believe, enter modern memory— as an ensemble and, in their vitally realized humanity, one by one.♦

To read responses, click here.

What, When, Where

Naoto Nakagawa: “1,000 Portraits of Hope.†Through August 8, 2012 at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, 112th Street and Amsterdam Ave., New York. (212) 316-7490 or www.stjohndivine.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller