Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Bloomer boy, or: An actor in spite of myself

My 15 minutes as Shakespeare

"No tights," I said. I would dress up as an Elizabethan king, but I wasn't going to wear tights at the re-opening of Shakespeare Park— the bit of land across Vine Street from the Free Library of Philadelphia's front door. I didn't know until last year that it was called Shakespeare Park. I knew the sculpture there, devoted to The Bard; I often ate lunch at a bench facing it, with Bob Gallagher, the poet and actor who would've been perfect for this job.

The Central Library on Vine between 19th and 20th, where I work, is in the midst of major renovations, and the project included an overhaul of the park, which had fallen on hard times. New landscaping, lighting, benches, plantings and irrigation have transformed it into an archetype of an urban oasis. Today was the day the protective fences would come down, and the Library's president and director would mark the occasion with brief words. I was to introduce her.

"You won't have to wear tights," an administrator assured me. Then I was handed over to the development people, whose agenda dictated otherwise. They wanted me to look, you know, like a King Henry. "King James, surely," I said, "if you're talking Shakespeare." But privately I was glad they didn't insist on Elizabeth herself. I'm a loyal soldier in the service of literacy and my beloved Free Library. But no dress.

About that crown….

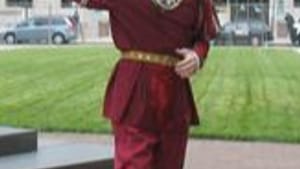

Well, the costume came in: tunic, belt, chain, bloomers, and... tights. But at this point, in for a dime, in for a dollar. And besides, the bloomers are downright modest.

Shoes? "I have brown loafers and black dress shoes, you know, like wingtips."

"Oh, they'll be perfect." Oh. Kay.

Then there was this crown. Wow, they really did mean a king. At this, I decided to throw down the not-included gauntlet.

"C'mon," I said. "Let's lose the crown. No crown."

"OK, fine," they readily agreed. What did they care? They'd found a guy from staff willing to dress up in a Shakespeare costume.

Henry or James?

Of course, nobody— least of all, me— knew whom I was supposed to be. Stripped of a crown, I wasn't recognizably Henry or James or anyone else. I couldn't be Shakespeare, since I would refer to him in my remarks. I was simply, as the tag attached to my tights stated, "Elizabethan." (Privately I cast myself as a Friend of Shakespeare.)

What saved me from the slough of jaundice, however, was the real reason I took on this chore: my speech. Here it is, as written by a very smart young staffer:

"Hear ye, hear ye, and welcome to the Free Library's re-opening of Shakespeare Park. The Bard himself knew of the importance and sanctity of finding nature in the midst of our busy existence. He wrote, "'And this, our life, exempt from public haunt, finds tongues in trees, books in running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in every thing.' Here to speak about this verdant space and its importance to the Free Library, is President and Director Siobhan A. Reardon. A hearty welcome to the good lady!"

Something about a city

That was it. That's what sold me. Forty-five seconds, but good stuff. It's utterly remarkable that a functionary writing for a petty bureaucrat in a special collection in a department in a city, would present these words to the public. As if it were a normal and a good and an admirable thing that a city would do— in the course of its city-ness— for itself, for its citizens, for its visitors, for its indigent, and even for soi-disant poets and composers nearby eating meatball sandwiches on lunch breaks, looking up at a sculpture and not knowing that this place had a name.

I memorized my speech, parsed it, massaged and analyzed it, brooded, added breaks, lifts, laughs, moved and mixed the words, practiced smiles, lifted eyebrows, waved hands, winked, gestured, barked, cooed and tried to say "Hear ye, hear ye" so it wouldn't sound like "Hear ye, hear ye." And practiced it all again and again.

How I ended up doing it at the time, I don't know. But I felt those trees, I knew those brooks, and inside I pined and cried for public exemption. I didn't care about tights or shoes, and even though I saw the looks of all the guys I work with who were thinking, "You've got. To. Be. Kidding," I wasn't embarrassed, not in the least.

Branagh, Olivier and me

When a reporter asked me afterward what I did for a living, and I said that I worked at the Library's Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music. "And you're a Shakespearean actor, of course," he replied.

I thought of Jacobi, and Branagh, and Olivier, and of my quasi-Irish-that-I-could-never-make-English accent, and of Robert Duvall asking Robert De Niro at the coffee counter in True Confessions if he wanted a piece of pie or something, and I thought of my portrayal of the Giant of Gath in Milton's Samson Agonistes 35 years ago, the last time I did anything like this, and I almost fainted.

I did manage, "Well, today." That was a lie, but I'm telling you, it sure felt good to take the place of one, for 45 seconds.

A mother brought her little daughter up to me. The little girl wanted to meet Shakespeare.

The Central Library on Vine between 19th and 20th, where I work, is in the midst of major renovations, and the project included an overhaul of the park, which had fallen on hard times. New landscaping, lighting, benches, plantings and irrigation have transformed it into an archetype of an urban oasis. Today was the day the protective fences would come down, and the Library's president and director would mark the occasion with brief words. I was to introduce her.

"You won't have to wear tights," an administrator assured me. Then I was handed over to the development people, whose agenda dictated otherwise. They wanted me to look, you know, like a King Henry. "King James, surely," I said, "if you're talking Shakespeare." But privately I was glad they didn't insist on Elizabeth herself. I'm a loyal soldier in the service of literacy and my beloved Free Library. But no dress.

About that crown….

Well, the costume came in: tunic, belt, chain, bloomers, and... tights. But at this point, in for a dime, in for a dollar. And besides, the bloomers are downright modest.

Shoes? "I have brown loafers and black dress shoes, you know, like wingtips."

"Oh, they'll be perfect." Oh. Kay.

Then there was this crown. Wow, they really did mean a king. At this, I decided to throw down the not-included gauntlet.

"C'mon," I said. "Let's lose the crown. No crown."

"OK, fine," they readily agreed. What did they care? They'd found a guy from staff willing to dress up in a Shakespeare costume.

Henry or James?

Of course, nobody— least of all, me— knew whom I was supposed to be. Stripped of a crown, I wasn't recognizably Henry or James or anyone else. I couldn't be Shakespeare, since I would refer to him in my remarks. I was simply, as the tag attached to my tights stated, "Elizabethan." (Privately I cast myself as a Friend of Shakespeare.)

What saved me from the slough of jaundice, however, was the real reason I took on this chore: my speech. Here it is, as written by a very smart young staffer:

"Hear ye, hear ye, and welcome to the Free Library's re-opening of Shakespeare Park. The Bard himself knew of the importance and sanctity of finding nature in the midst of our busy existence. He wrote, "'And this, our life, exempt from public haunt, finds tongues in trees, books in running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in every thing.' Here to speak about this verdant space and its importance to the Free Library, is President and Director Siobhan A. Reardon. A hearty welcome to the good lady!"

Something about a city

That was it. That's what sold me. Forty-five seconds, but good stuff. It's utterly remarkable that a functionary writing for a petty bureaucrat in a special collection in a department in a city, would present these words to the public. As if it were a normal and a good and an admirable thing that a city would do— in the course of its city-ness— for itself, for its citizens, for its visitors, for its indigent, and even for soi-disant poets and composers nearby eating meatball sandwiches on lunch breaks, looking up at a sculpture and not knowing that this place had a name.

I memorized my speech, parsed it, massaged and analyzed it, brooded, added breaks, lifts, laughs, moved and mixed the words, practiced smiles, lifted eyebrows, waved hands, winked, gestured, barked, cooed and tried to say "Hear ye, hear ye" so it wouldn't sound like "Hear ye, hear ye." And practiced it all again and again.

How I ended up doing it at the time, I don't know. But I felt those trees, I knew those brooks, and inside I pined and cried for public exemption. I didn't care about tights or shoes, and even though I saw the looks of all the guys I work with who were thinking, "You've got. To. Be. Kidding," I wasn't embarrassed, not in the least.

Branagh, Olivier and me

When a reporter asked me afterward what I did for a living, and I said that I worked at the Library's Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music. "And you're a Shakespearean actor, of course," he replied.

I thought of Jacobi, and Branagh, and Olivier, and of my quasi-Irish-that-I-could-never-make-English accent, and of Robert Duvall asking Robert De Niro at the coffee counter in True Confessions if he wanted a piece of pie or something, and I thought of my portrayal of the Giant of Gath in Milton's Samson Agonistes 35 years ago, the last time I did anything like this, and I almost fainted.

I did manage, "Well, today." That was a lie, but I'm telling you, it sure felt good to take the place of one, for 45 seconds.

A mother brought her little daughter up to me. The little girl wanted to meet Shakespeare.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kile Smith

Kile Smith