Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Eve of destruction

Museum at Chemical Heritage Foundation presents 'Things Fall Apart'

Things aren’t actually disintegrating at the Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum (CHF)…but they will, which is the point of Things Fall Apart.

Being haunted by memories of high-school chemistry, which I survived only because of a great teacher and a patient lab partner, I’d avoided the museum, which is devoted to the role of chemistry in human life. That title made me look.

Lately, things seem to be crumbling everywhere. Who hasn’t felt like Humpty Dumpty, up on a shaky ledge, looking down? Yet CHF’s title seemed to imply hope, as if to say, “Things fall apart…but that’s okay!" Maybe it’s only one of the chemistry-induced delusions to which I am prone. Ask my former lab partner.

Destruction and preservation

Curator Elisabeth Berry Drago has gathered items from across the Philadelphia area, among them locks from Eastern State Penitentiary, a door from Independence National Historical Park, and redware chamberpots and bone buttons from the city almshouse, which once stood on CHF’s Old City location. Visitors who want even more decomposition can download a walking tour of the neighborhood.

Things Fall Apart is about more than destruction, however. It examines what culture deems trash and treasure, and the lengths taken to preserve valued possessions. Who hasn’t spent hours reassembling a cherished item, like the owner of a shattered 1952 commemorative plate from St. Martin’s Church in Marcus Hook? It’s on display, held together by Elmer’s glue.

Contemporary art mingles with the artifacts, providing commentary on the lifecycles of things. Particularly resonant is fiber artist Aubrie Costello’s enormous white banner, emblazoned “Kindness Doesn’t Indicate Weakness” in dripping red silk letters. It’s a flag that should be flown across America.

From patinas to plastics

An item’s surface can tell the story of its life. How often Eastern State’s 1920-vintage padlocks were handled and where they were installed shows in their patinas, which vary by chemical composition, color, and destructiveness. Stable patinas prolong an item’s life, while unstable, corrosive ones shorten it.

Nor is plastic immune. In The Graduate, “plastics” was presented as the key to success for young Benjamin Braddock. When the film was made in 1967, plastic flooded modern life with items thought better in every way: lighter, cheaper, more colorful, indestructible. Fifty years later, the truth is seeping out.

Witness poor Barbie, circa 1960, disintegrating on a pink divan in a display case. She still looks good, but if we touched her, she’d feel sticky. Barbie’s legs ooze plasticizers that attract a fine layer of dust, turning them faintly gray, as though she ran out of Nair. On the upside, if Barbie’s feet are as tacky as her legs, she might finally be able to keep those stupid shoes on.

According to CHF’s exhibition, most plastics are unlikely to survive a generation in stable condition. Conserving plastic is difficult because labs cooked up so many chemical variations. Think of the brand names that litter everyday conversation: Plexiglas, polyester, polyurethane, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and so forth. A list compiled by England’s Museum of Design in Plastics has 24 entries just under “P.” Things don’t look good for Barbie.

Eau de library

Conserving paintings and books is more straightforward, because these reside in a more limited chemical universe. The key is determining the chemicals comprising and compromising a work, a process assisted by microscopy. Did the work encounter dirt, pollutants, mold, and perhaps residue from an earlier, less enlightened restoration?

Interestingly, human saliva is one of the safest solvents for cleaning canvases, the natural enzymes working as well on grimy paintings as they do on grimy cheeks. Let’s assume that good nonbiological alternatives have been found.

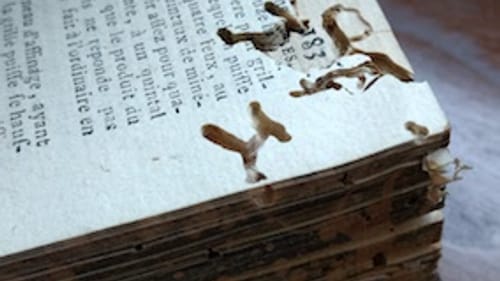

Like paintings, books can be damaged by light and moisture, and even well-kept collections can have a faintly musty odor, a vaguely comforting scent reminiscent of libraries. Despite their vulnerabilities, books seem able to withstand punishment. Dennis Diderot’s 1780 Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts remains legible, though its pages bear lacy holes from psocoptera, insects that nibble paper.

Beautiful decay

Destruction doesn’t have to be ugly. An 1,800-year-old Roman flask, for example, was transformed into a rainbow-patterned vessel through crizzling, a process of decay found in archaeological glass. The effect is so attractive it inspired Louis Comfort Tiffany to replicate it, and the style became the highly prized signature of Tiffany art glass.

Although Things Fall Apart does not reveal permanent antidotes to destruction, it’s worthwhile to understand the natural processes that dismantle our possessions and (let’s admit it) ourselves. Like a roomful of old books, decay can be comforting or, like rainbow-colored glass, beautiful. Though it can sometimes be put off, it can’t be avoided. It’s no one’s fault; things just fall apart.

What, When, Where

Things Fall Apart. Through February 2, 2018, at the Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum, 315 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. (215) 925-2222 or chemheritage.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.