Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Monumental future

Mural Arts Program's Monument Lab brought public art to the people

Mural Arts sure picked an anxious time to launch Monument Lab, its new public-art program. Cities all over the country are coming to terms with some twisted narratives resting atop or tumbling from pedestals in their streets and parks. But perhaps all that soul-searching also makes the project even more timely.

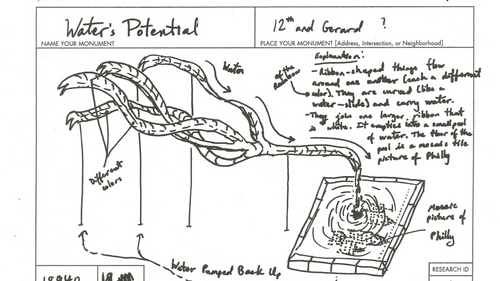

For nine weeks this fall, Monument Lab invited speculation into what and how we think about our city. The project installed 20 temporary monuments by 10 artists and asked both creators and people on the street, “What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?” The answers have been a breath of fresh air, injecting new life into a civic conversation that was starting, frankly, to seem like a lot more trouble than it was worth.

Years in the making, Monument Lab (curated by historian Paul Farber and artist Ken Lum, both University of Pennsylvania faculty) set out to offer a fresh start for the troubled genre. In this public-art situation, artists didn’t defer to political or commercial powers but rather to public citizens. Its monuments were all temporary, giving artists freedom and flexibility in what can be one of art’s stodgiest forms, and encouraging them to explore subjects outside of received history.

As a result, the city had nine weeks of exciting, often moving work on its parks and streets. Not surprisingly, the sculptures brought local issues to the fore with the kind of nuance and mystery art does so well.

Leaving an impact

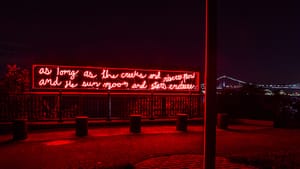

At Fishtown’s Penn Treaty Park, with the Delaware River behind, Ontario-based Omaskêko Ininiwak/Moose Cree First Nation artist Duane Linklater’s neon "In Perpetuity" hovered magically in the air. The piece bears a quote from the 1682 peace agreement between William Penn and Lenni Lenape chief Tamanend. The agreement was supposed to last “as long as the creeks and rivers flow.” Its neon is bent to mimic Linklater's nine-year-old daughter Sassa's handwriting.

Over on Broad Street, Cuban-American artist Tania Bruguera’s figure in unfired clay, titled “Monument to New Immigrants,” quickly disintegrated in rain and weather and was replaced at its Lenfest Plaza site by duplicates; coming across them in one of their wrecked phases was a profound and moving experience.

Monument Lab also produced many more sculptures, along with programs, events, and discussions.

The prototypes are gone, but the project remains. Both its visible and invisible elements are available online. You can view the sculptures and read through 5,000 new crowdsourced proposals collected at each monument site by a small army of enthusiastic staffers. Those proposals live on at monumentlab.com. Click “Research,” then “Interactive Map”; it’s worth it.

A "collective monument"

Browsing through these suggestions is like spending time with your neighbors at their sunniest. They propose work such as “a monument to my first kiss.” A Roman centurion or soldier in fatigues might be “standing guard over the parks, the animals, and the community.”

In a way, these proposals, scratched in Sharpie on clipboards by passersby, are a collective ideal monument. They emerge as an immensely satisfying picture of Philadelphia: a continual work in progress and chorus of many discrete voices.

Cities working hard to provide modern commentary and contextualize their old art might note how handsomely new art did the job here. Linklater’s piece, for instance, shared the area with four other permanent monuments (one of them Philadelphia’s very first public monument, dated 1827, the others from the 1980s and ‘90s). The busy little park with its dogwalkers and children’s playground became a free-floating dissertation across centuries on what is gained and lost in negotiations between cultures, whether in treaties or through the process of gentrification.

After this year, it’s true, we may never look at civic art in quite the same way again. But like many painful challenges, examining the old in a new light can also be a great moment for growth and change. People planning responsible permanent monuments from now on might well be aware of Monument Lab's well-honed strategies for community engagement. Monuments that thoughtfully explore the hopes and dreams of everyday people might, perhaps, be a most fitting permanent legacy of our generation.

A Monument Lab project catalogue is being prepared for publication by Temple University Press.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anne Schuster Hunter

Anne Schuster Hunter