Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Democracy is never finished

MOAR presents ‘World Affairs and the Enduring American Revolution: Women’s Rights’

In 2020, nothing, no matter how mundane, can be taken for granted. Not buying groceries, having a job, going to school, riding a bus, and certainly not voting.

In conjunction with the Museum of the American Revolution’s (MOAR) new exhibition, When Women Lost the Vote: A Revolutionary Story, 1776 to 1807, a livestreamed panel discussion titled World Affairs and the Enduring American Revolution: Women’s Rights explored women’s political participation. Presented by the MOAR and the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, the October 13 conversation covered women’s status from the perspectives of journalism, history, foreign policy, and public affairs. Panelists offered observations on inequities faced, both in the United States and internationally, by half the world’s population.

When women decide

Errin Haines, editor-at-large and cofounder of the new nonpartisan newsroom The 19th, moderated. Haines, an award-winning journalist, has written on race, ethnicity, and gender for the Associated Press and is a commentator for MSNBC and other networks.

Named for the constitutional amendment granting women the vote a century ago, The 19th was established to counteract gender bias in news coverage. The platform reports on gender, politics, and policy. “[In this year’s election] we know women will be the deciders,” Haines said. “We are not a special-interest group, but the majority of the electorate.”

Not all American women won the vote in 1920. Indigenous women couldn’t vote until passage of The Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. Asian Americans waited until the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 granted them citizenship, and many Black citizens were illegally denied access to the polls until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

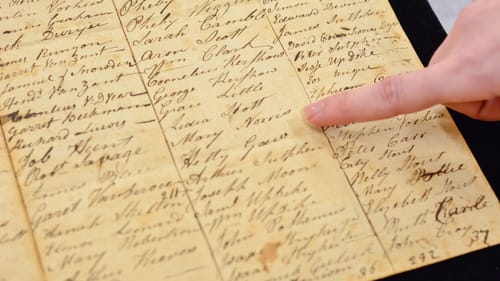

The New Jersey miracle

Remarkably, there was a temporary glimmer of gender equality in 1776. Panelist Rosemarie Zagarri, a professor of history at George Mason University and the author of 2008’s Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic, related the story of colonial women in New Jersey who benefited from presciently gender-neutral wording in the state constitution. It specified that land-owning “inhabitants” could vote, which qualified single women and widows. Married women, precluded from owning property, were excluded.

“Women were voting on the same terms as men,” Zagarri said. “In some local elections, up to 10 percent of voters were women.” But the New Jersey miracle didn’t last. Women’s enfranchisement had always been controversial—opponents claimed women lacked intelligence, were puppets, and engaged in fraud by changing clothes and voting twice. Legislators finally restored the imbalance of power in 1807, decreeing that all white men, and no one else, could vote.

Colonial women were politically active regardless, Zagarri said: “Women started to become more involved in the politics of the streets in the run-up to the Revolution.” They protested the imposition of British taxes by boycotting tea and fine fabrics. They raised funds to support Continental forces, and expressed support for the American cause in poetry and plays. Women acted as political agents within the family, inculcating patriotism in children, and encouraging husbands to accept civic responsibilities. Zagarri has described these contributions as "republican motherhood."

The United States is far behind

Though American women continue to influence the republic, they do not yet occupy their share of seats at the table. The United States ranks 125th in gender parity among the world’s 193 nations, according to the Women's Power Index. The index, compiled by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), is indicative of the percentage of government executive and legislative positions held by women. Nations currently topping the WPI are Costa Rica, Rwanda, and Sweden.

“Many countries have far outpaced the United States when it comes to women’s participation in politics at the highest level,” explained Rachel B. Vogelstein, senior fellow and director of CFR’s women and foreign policy program. Just 22 nations presently have a female head of state, 14 countries have achieved parity in cabinet appointments, and only four have equal legislative representation. In the US, 24 percent of Congress is female, 17 percent of current cabinet members are women, and technically, we’ve not yet elected a woman president, though, as Vogelstein pointed out, “the majority of US voters in 2016 cast their vote for a woman.” Achieving political parity matters, she said, because the increased involvement of women in leadership has been shown to promote government bipartisanship, equality, and stability.

Women in Philadelphia

Jovida Hill, executive director of Philadelphia’s Office of Engagement for Women, turned the discussion to the local level. The office, charged with promoting economic, educational, and social opportunities for women and girls, has pursued issues Hill called “the most progressive initiatives in the nation,” including wage equity, fair workweek and minimum wage legislation, the domestic workers’ bill of rights, maternal mortality, human trafficking, sexual and street harassment, and dignity for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women.

Whether voting, running for, or serving in office, women’s likelihood of exercising political rights depends on a constellation of factors. “There is no gender justice without economic justice or without racial justice,” Hill said. “Without economic justice, social justice will remain elusive.”

Hill emphasized efforts to inspire women through role models such as Crystal Bird Faucet. In 1938, Faucet was elected by a majority-white district in Philadelphia as its representative to the Pennsylvania House, thus becoming the first Black woman in the United States elected to a state legislature. During her presentation Hill, a filmmaker, presented Unerased: A Black Woman's Love Song, a video “dedicated to Black women, their power, perseverance, and sturdy shoulders.”

Caring for democracy

The wide-ranging discussion, which coincided with the opening of MOAR’s new exhibition (going virtual in November for patrons at home), kept circling back to the current moment, which is undermining American institutions and values, abandoning norms, and making dark predictions of fraudulent elections. The legitimacy of American democracy faces a clear threat, and not for the first time. Panelists emphasized that democracy requires care to thrive.

“Voting is a right and a privilege that must be cherished and exercised,” Zagarri said, observing that in 1807, there was no record of women protesting when they lost the vote.

Hill said that she’s encouraged to see lines of Philadelphians dropping off ballots, and she repeated advice for anyone discouraged with the present situation: “The more you try to take away our vote, the more we want to vote.”

Image description: a small pile of red, white, and blue stickers that say “I vote” on them. They’re lying on blue cloth waiting to be picked up and worn.

Image description: A photo of a piece of paper, brown with age and covered with a long list of names in narrow ink handwriting. A finger is pointing to the name “Mary Norris,” one among many that are legible.

What, When, Where

World Affairs and the Enduring American Revolution: Women’s Rights. A discussion panel livestreamed on October 13, 2020, presented by the Museum of the American Revolution and the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia. Moderated by Errin Haines.

When Women Lost the Vote: A Revolutionary Story, 1776 to 1807 runs through April 25, 2021 at the Museum of the American Revolution, 101 South 3rd St., Philadelphia. (215) 253-6731 or amrevmuseum.org. Watch for updates on a virtual version of the exhibition this November.

The Museum of the American Revolution is an ADA-compliant venue. For more information on visiting, contact Guest Services at 267-579-3596 Voice/TTY or email [email protected]. Learn about MOAR’s COVID safety precautions at the museum's website.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.