Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Move Strindberg to South Africa, and what do you get?

"Mies Julie' in Brooklyn

The lights go down, the play is over, but the audience sits frozen in silence. Eventually, applause breaks out for the exhausted cast of the most shattering show on the New York stage this fall. But it's applause from an audience that's almost too stunned to respond.

Such, reportedly, is the reaction to Mies Julie at St. Ann's Warehouse every night, and certainly at the performance I saw last weekend. Not only is it the most shattering show in town, it's also the most violent, sexually explicit and contextually insightful play I've seen in a long time.

The South African Yael Farber's inspired adaptation of Strindberg's searing melodrama Miss Julie sets the play in a farmhouse on the remote Karoo desert in South Africa, a far cry from late-19th-Century Sweden where it was originally imagined. The original took place in 1874 on Midsummer's Eve, but Farber's adaptation is set in 2012 on Freedom Day, the anniversary of the end of apartheid.

And yet by updating and transplanting the play, Farber has not only preserved the power of Strindberg's work, she's also expanded its boundaries and intensified its themes.

Life and death struggle

The original addressed the issues of power, class and sexual domination in a repressive, rigid, insular, misogynistic society. Farber's adaptation preserves this potent mix and adds to it a life-and-death struggle between the races, as well as issues of homeland, national identity and familial love.

The result is an explosion the likes of which I've rarely seen on stage.

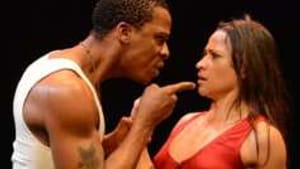

The scene is the kitchen of the family farmhouse. The cast includes Julie (played by the courageous Hilda Cronje), a beautiful, troubled 18 year old, daughter of the all-powerful white farm owner (an omnipresent, though off-stage, figure). There's also John (the graceful Bongile Mantsai), a young black servant in his 20s, and his mother Christine (the regal Thoko Ntshinga), another family servant, who raised Julie and John together.

From the moment the play begins, the heat in that kitchen keeps rising (steam literally pours on stage) and doesn't stop until the play's devastating conclusion.

Sexual goading

John sits quietly, polishing his master's boots. Meanwhile, Julie stalks the stage like a caged tigress. She taunts John and won't let up, daring him to dance with her at the Freedom Day festivities. She plays with him as she did when they were children, but it's an adult game now.

"Be a man tonight, not a boy!" she cries, goading him to defy her father, while at the same time reminding him that her father would shoot him if he does.

John tries to keep his cool, as well as his place, but in that combustible kitchen it's impossible. As the heat rises, so do the stakes.

Lured in

Julie's taunts are explicitly sexual, and her eyes gleam with a complex mixture of terror and thrill. Julie and John dance for a moment, and their pas de deux alternates between sexual heat and the threat of violence.

As the pressure escalates, John is lured in, inexorably. Julie offers him a glass of her father's vintage wine; emboldened, he drinks from the bottle.

"Kiss my foot!" Julie dares John. There's no turning back now, and the inevitable sexual assault that follows is brutal and savage.

Blood on the skirt

After that shocking turning point, a bloodbath ensues"“ its first signs seeping through Julie's silk skirt (she was a virgin) and spotting the floor of that same kitchen where her mother shot herself years ago.

Yes, there are fleeting moments of hope. Julie and John alternately declare love for each other. Julie entreats John to run away with her. But those moments are as flimsy and as gossamer as Julie's garb, now torn and blood-soaked.

Instead, the ferocious power struggle escalates. "You're mine!" Julie cries.

"You're my kaffir now!" John roars, as they alternate in the master/slave roles, each claiming ownership over the other as if their bodies were territories, each claiming ownership of the land Julie's father wrested from John's ancestors.

Mother as bedrock

Farber, clearly, sees this power struggle as a metaphor for her country today. "Welcome to the new South Africa." John cries, "where miracles leave us exactly where we began."

Watching it all is the stoical Christine, John's mother and the bedrock of the play. In Strindberg's original, Christine was John's fiancée. By instead reimagining Christine as John's mother (and Julie's surrogate mother), Farber has designated Christine to represent the continuum of South Africa's tragic history and its legacy of racial hatred and inequality, unresolved even after apartheid.

Helpless in the face of their struggle, Christine can only keep on cleaning the kitchen and scrubbing the floor, as she has done her whole life— as all the Christines before her under apartheid have done. After all, she explains, this is her home and homeland, too.

In the end, she forsakes that bloody kitchen to go to Sunday church, leaving Julie and John trapped in it, battling to the bloody, horrific end.

Farber has added yet another rich dimension to the Strindberg original: a ghost, embodied by an African woman in traditional garb. This timeless spirit circles the kitchen, chanting haunting African songs, playing ancient instruments, accompanied by a two-piece orchestra at the stage's edge. Hers is a lament for South Africa as it struggles to wash the blood away "“ that blood of the past that seems to keep seeping into the present.

Such, reportedly, is the reaction to Mies Julie at St. Ann's Warehouse every night, and certainly at the performance I saw last weekend. Not only is it the most shattering show in town, it's also the most violent, sexually explicit and contextually insightful play I've seen in a long time.

The South African Yael Farber's inspired adaptation of Strindberg's searing melodrama Miss Julie sets the play in a farmhouse on the remote Karoo desert in South Africa, a far cry from late-19th-Century Sweden where it was originally imagined. The original took place in 1874 on Midsummer's Eve, but Farber's adaptation is set in 2012 on Freedom Day, the anniversary of the end of apartheid.

And yet by updating and transplanting the play, Farber has not only preserved the power of Strindberg's work, she's also expanded its boundaries and intensified its themes.

Life and death struggle

The original addressed the issues of power, class and sexual domination in a repressive, rigid, insular, misogynistic society. Farber's adaptation preserves this potent mix and adds to it a life-and-death struggle between the races, as well as issues of homeland, national identity and familial love.

The result is an explosion the likes of which I've rarely seen on stage.

The scene is the kitchen of the family farmhouse. The cast includes Julie (played by the courageous Hilda Cronje), a beautiful, troubled 18 year old, daughter of the all-powerful white farm owner (an omnipresent, though off-stage, figure). There's also John (the graceful Bongile Mantsai), a young black servant in his 20s, and his mother Christine (the regal Thoko Ntshinga), another family servant, who raised Julie and John together.

From the moment the play begins, the heat in that kitchen keeps rising (steam literally pours on stage) and doesn't stop until the play's devastating conclusion.

Sexual goading

John sits quietly, polishing his master's boots. Meanwhile, Julie stalks the stage like a caged tigress. She taunts John and won't let up, daring him to dance with her at the Freedom Day festivities. She plays with him as she did when they were children, but it's an adult game now.

"Be a man tonight, not a boy!" she cries, goading him to defy her father, while at the same time reminding him that her father would shoot him if he does.

John tries to keep his cool, as well as his place, but in that combustible kitchen it's impossible. As the heat rises, so do the stakes.

Lured in

Julie's taunts are explicitly sexual, and her eyes gleam with a complex mixture of terror and thrill. Julie and John dance for a moment, and their pas de deux alternates between sexual heat and the threat of violence.

As the pressure escalates, John is lured in, inexorably. Julie offers him a glass of her father's vintage wine; emboldened, he drinks from the bottle.

"Kiss my foot!" Julie dares John. There's no turning back now, and the inevitable sexual assault that follows is brutal and savage.

Blood on the skirt

After that shocking turning point, a bloodbath ensues"“ its first signs seeping through Julie's silk skirt (she was a virgin) and spotting the floor of that same kitchen where her mother shot herself years ago.

Yes, there are fleeting moments of hope. Julie and John alternately declare love for each other. Julie entreats John to run away with her. But those moments are as flimsy and as gossamer as Julie's garb, now torn and blood-soaked.

Instead, the ferocious power struggle escalates. "You're mine!" Julie cries.

"You're my kaffir now!" John roars, as they alternate in the master/slave roles, each claiming ownership over the other as if their bodies were territories, each claiming ownership of the land Julie's father wrested from John's ancestors.

Mother as bedrock

Farber, clearly, sees this power struggle as a metaphor for her country today. "Welcome to the new South Africa." John cries, "where miracles leave us exactly where we began."

Watching it all is the stoical Christine, John's mother and the bedrock of the play. In Strindberg's original, Christine was John's fiancée. By instead reimagining Christine as John's mother (and Julie's surrogate mother), Farber has designated Christine to represent the continuum of South Africa's tragic history and its legacy of racial hatred and inequality, unresolved even after apartheid.

Helpless in the face of their struggle, Christine can only keep on cleaning the kitchen and scrubbing the floor, as she has done her whole life— as all the Christines before her under apartheid have done. After all, she explains, this is her home and homeland, too.

In the end, she forsakes that bloody kitchen to go to Sunday church, leaving Julie and John trapped in it, battling to the bloody, horrific end.

Farber has added yet another rich dimension to the Strindberg original: a ghost, embodied by an African woman in traditional garb. This timeless spirit circles the kitchen, chanting haunting African songs, playing ancient instruments, accompanied by a two-piece orchestra at the stage's edge. Hers is a lament for South Africa as it struggles to wash the blood away "“ that blood of the past that seems to keep seeping into the present.

What, When, Where

Mies Julie. Adapted and directed by Yael Farber, from August Strindberg’s Miss Julie. Through December 16, 2012 at St. Ann’s Warehouse, 29 Jay St., Brooklyn, NY. www.stannswarehouse.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.