Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Machine Age man

Michener Art Museum presents 'Charles Sheeler: Fashion, Photography, and Sculptural Form'

Don’t let the title of the James A. Michener Art Museum's current show mislead you. Sure, the venue displays Charles Sheeler’s stunning fashion and portrait photography and his brief dabbling in textile design. But “sculptural form" is a vague term to explain how the artist’s powerful paintings of the Machine Age relate to his other endeavors.

Sheeler (1883-1965) was first and foremost a Philadelphia painter who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, was influenced by European Modernism, and later developed a style known as Precisionism. But while the show juxtaposes Sheeler’s dramatic photos for Condé Nast magazines with mannequins displaying 1920s haute couture, the show’s emphasis lies elsewhere. Which begs the question: Why would a serious artist take photos of the rich and famous for Vanity Fair and Vogue? Because he wanted to eat.

Film work

Sheeler was a self-taught photographer who supplemented his income with architectural photography. Sheeler’s 1921 film Manhatta, created in collaboration with photographer Paul Strand, stands out as an exhibition highlight. The nine-minute film documents the frenetic growth of New York’s skyline, along with its fog of pollution. Following this film, he worked for Condé Nast magazines for five years on the cusp of the Great Depression, photographing disaffected society women draped in furs and dripping with jewels.

I found these images strongly reminiscent of Paris Vogue contributor Berenice Abbott’s fashion photography. Abbott’s 1927 photo of Jean Cocteau, part of the Barnes Foundation’s 2016 French Vintage Photography exhibition, speaks volumes to Sheeler’s images of actress Norma Shearer and a youthful Aldous Huxley. Sheeler traveled to Paris and had to be aware of Vogue photographers such as Abbott.

While 1931 wasn’t a good year for the stock market, it was a great year for Sheeler. Vogue subscribers were hocking their diamonds, but Sheeler found representation at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in New York. No more portraits of society doyennes. No more messing around with textiles. He could now focus exclusively on painting.

Style and substance

Working from photos he took of American industry while on assignment for Fortune magazine, Sheeler turned out monumental paintings on the theme of power: locomotives, power plants, airplanes, and dams. A few, but not nearly enough, of these images compose the backdrop for the exhibition’s display of 1920s high fashion.

However, fans of fashion and photography will not be disappointed. The exhibition brims with sequin-laden flapper gowns I wanted to rip off the mannequins and Charleston out the door, if not for the security guards. Black-and-white photographs of 1920s movie stars, actors, writers, and models are wondrous.

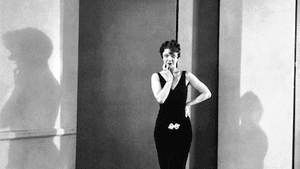

Best in show? Sheeler’s 1928 photo of Bobbe Arnst for Vanity Fair in which Arnst is dwarfed by the stark ambiance Sheeler created in his studio, throwing strong shadows in two directions. The image demonstrates Sheeler’s ability to incorporate Machine Age design with fashion photography. It also documents America’s fascination with fame and fortune just before the Depression swept it all away.

Considering that these photos have not been exhibited in 90 years, this show has a lot to say about our nation’s current polarization. Meanwhile, I am going to curl up with the latest edition of Vanity Fair to see how the 1 percent is doing today.

What, When, Where

Charles Sheeler: Fashion, Photography, and Sculptural Form. Through July 9, 2017, at the James A. Michener Art Museum, 138 S. Pine Street, Doylestown. (215) 340-9800 or michenerartmuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Stacia Friedman

Stacia Friedman