Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Coming of age by turning the other cheek

McCraney's "Choir Boy' in New York

Growing up gay and black in the American South can't be without its challenges. Perhaps that's why Tarell Alvin McCraney's humane new play, Choir Boy, is so affecting.

Unlike numerous other contemporary plays and films about cruelty, discrimination and homophobia that fight fire with fire, this tender coming-of-age play shows that rage isn't necessarily the best response. McCraney's more effective arsenal includes resilience, humor and song.

Choir Boy tells the story of Pharus Jonathan Young, and his final years at the all-black Charles R. Drew Prep School. In the opening scenes, we hear Pharus being taunted by schoolmates while he sings in a choir concert. The terms "sissy," "faggot" and even the hateful "n" word ring out, and yet Pharus refuses to tell the headmaster who uttered these epithets. (They happen to have been spoken by the headmaster's own nephew, Bobby.)

Effeminate gestures

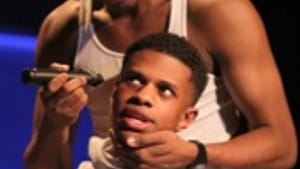

But we don't feel sorry for Pharus. As played by the gifted young actor/singer Jeremy Pope, Pharus knows how to take care of himself. He's a scholarship student and the leader of the school choir. So he uses his power judiciously and effectively to fight back against his tormentors.

Moreover, he's clear about his gayness, and doesn't try to hide it. For him, the issue is learning how to balance respect for a tradition (church and school) that's homophobic and therefore hostile toward him, and at the same time remain true to himself.

"Pharus: your wrist!" the headmaster admonishes Pharus about his mannerisms, which are openly characterized as effeminate. (Pharus meets this disapproval with a hearty dose of humor.)

Sexual arousal

In individual scenes with each of the five other boys in the cast, we follow Pharus's struggle to relate to his fellow choir mates in his quest for friendship and even affection. Bobby, the headmaster's nephew, openly taunts him for his gayness. Another boy, Anthony, wrestles with Pharus, provoking an excruciatingly embarrassing moment of sexual arousal that Pharus tries desperately to hide.

Pharus's handsome and hunky roommate AJ, on the other hand, is both objective and compassionate. When Pharus flirts with AJ, the latter gently but firmly rebuffs him, retorting: "Who you saving it for?

"Jesus," Pharus replies readily.

"I don't think Jesus is interested," AJ responds.

Code of silence

The penultimate conflict occurs when David, another boy, beats up Pharus in the shower (it's not clear whether Pharus actually made a pass at David, or David anticipated it, or whether David might even have been threatened because of his own nascent gay feelings). As in the incident of Bobby's verbal abuse, Pharus refuses to reveal his attacker's identity. After all, Pharus maintains, he's keeping the school honor code— one that disapproves of naming names.

"I always expected that everyone would hate Pharus," says Mr. Pendleton, a Drew teacher and the only white character in the play (portrayed with wry amusement by Austin Pendleton). "I wasn't expecting anyone to love him."

Yet as this moving play illustrates, that is just what happens. On the evening before the graduation, AJ invites the wounded Pharus to sleep next to him in his bed. It's a delicate, platonic, asexual expression of true compassion and comfort from one friend to another. Pharus has prevailed, maintaining his integrity and identity, and emerging triumphant on graduation day.

Comfort in spirituals

Interspersed between these scenes, the six boys— all choir members— burst into soaring song. Their spirituals, including "I've been in the storm so long" and "Sometimes I feel like a motherless child," bear lyrics that articulate the play's themes.

These songs, as Pharus says, "born of oppression, have become beacons of hope." McCraney, like August Wilson before him, writes of the African-American's struggle for identity that expresses itself in the triumph of song and the individual's uplifted voice.

Choir Boy calls to mind another moving coming-of-age play "“ Alan Bennett's History Boys. In that play's final scene, the young graduates sing the sad strains of "Bye Bye Blackbird," expressing the same bittersweet passage from youth to manhood that the young choirboys of McCraney's play have reflected in their own spirituals.

McCraney's Pharus graduates from school into life with an advanced degree in courage, endurance, resilience and humor. His diploma reads "acceptance" and his song— that is, his identity— remains intact.

Unlike numerous other contemporary plays and films about cruelty, discrimination and homophobia that fight fire with fire, this tender coming-of-age play shows that rage isn't necessarily the best response. McCraney's more effective arsenal includes resilience, humor and song.

Choir Boy tells the story of Pharus Jonathan Young, and his final years at the all-black Charles R. Drew Prep School. In the opening scenes, we hear Pharus being taunted by schoolmates while he sings in a choir concert. The terms "sissy," "faggot" and even the hateful "n" word ring out, and yet Pharus refuses to tell the headmaster who uttered these epithets. (They happen to have been spoken by the headmaster's own nephew, Bobby.)

Effeminate gestures

But we don't feel sorry for Pharus. As played by the gifted young actor/singer Jeremy Pope, Pharus knows how to take care of himself. He's a scholarship student and the leader of the school choir. So he uses his power judiciously and effectively to fight back against his tormentors.

Moreover, he's clear about his gayness, and doesn't try to hide it. For him, the issue is learning how to balance respect for a tradition (church and school) that's homophobic and therefore hostile toward him, and at the same time remain true to himself.

"Pharus: your wrist!" the headmaster admonishes Pharus about his mannerisms, which are openly characterized as effeminate. (Pharus meets this disapproval with a hearty dose of humor.)

Sexual arousal

In individual scenes with each of the five other boys in the cast, we follow Pharus's struggle to relate to his fellow choir mates in his quest for friendship and even affection. Bobby, the headmaster's nephew, openly taunts him for his gayness. Another boy, Anthony, wrestles with Pharus, provoking an excruciatingly embarrassing moment of sexual arousal that Pharus tries desperately to hide.

Pharus's handsome and hunky roommate AJ, on the other hand, is both objective and compassionate. When Pharus flirts with AJ, the latter gently but firmly rebuffs him, retorting: "Who you saving it for?

"Jesus," Pharus replies readily.

"I don't think Jesus is interested," AJ responds.

Code of silence

The penultimate conflict occurs when David, another boy, beats up Pharus in the shower (it's not clear whether Pharus actually made a pass at David, or David anticipated it, or whether David might even have been threatened because of his own nascent gay feelings). As in the incident of Bobby's verbal abuse, Pharus refuses to reveal his attacker's identity. After all, Pharus maintains, he's keeping the school honor code— one that disapproves of naming names.

"I always expected that everyone would hate Pharus," says Mr. Pendleton, a Drew teacher and the only white character in the play (portrayed with wry amusement by Austin Pendleton). "I wasn't expecting anyone to love him."

Yet as this moving play illustrates, that is just what happens. On the evening before the graduation, AJ invites the wounded Pharus to sleep next to him in his bed. It's a delicate, platonic, asexual expression of true compassion and comfort from one friend to another. Pharus has prevailed, maintaining his integrity and identity, and emerging triumphant on graduation day.

Comfort in spirituals

Interspersed between these scenes, the six boys— all choir members— burst into soaring song. Their spirituals, including "I've been in the storm so long" and "Sometimes I feel like a motherless child," bear lyrics that articulate the play's themes.

These songs, as Pharus says, "born of oppression, have become beacons of hope." McCraney, like August Wilson before him, writes of the African-American's struggle for identity that expresses itself in the triumph of song and the individual's uplifted voice.

Choir Boy calls to mind another moving coming-of-age play "“ Alan Bennett's History Boys. In that play's final scene, the young graduates sing the sad strains of "Bye Bye Blackbird," expressing the same bittersweet passage from youth to manhood that the young choirboys of McCraney's play have reflected in their own spirituals.

McCraney's Pharus graduates from school into life with an advanced degree in courage, endurance, resilience and humor. His diploma reads "acceptance" and his song— that is, his identity— remains intact.

What, When, Where

Choir Boy. By Tarell Alvin McCraney; Trip Cullman directed. Manhattan Theatre Club production through August 11, 2013 at The Studio at Stage II, New York City Center, 131 West 55th St., New York. www.manhattantheatreclub.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.