Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A 'Great' eight

McCarter Theatre Center presents Elevator Repair Service’s 'Gatz'

Gatz, which recently played a three-performance engagement at Princeton, New Jersey’s McCarter Theatre Center, may be the most unlikely phenomenon in recent theater history. The production, created by the performance collective Elevator Repair Service (ERS), has extensively toured the US and beyond for more than a decade. It enacts F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby over the course of eight hours — including a complete recitation of the novel. If you read this and think it sounds like a weird, voluntary form of Saturday detention for adults, I won’t blame you.

Neither accolade nor apostate

I started out as a total skeptic. The contrarian in me couldn’t imagine the show — which the New York Times called “the most remarkable achievement in theater not only of this year but also of this decade” — would live up to its hype. Endurance-testing run times and literary adaptations in general ping high on my pretension meter. I passed up previous chances to catch it, including its stand at the Philadelphia Fringe Festival in 2007 and its earlier stop at McCarter in 2011.

Now that I’ve seen it, I find myself divided: neither an acolyte nor an apostate. Gatz won’t make my best-of list for 2019, much less the decade, and the adaptation doesn’t earn every minute of its expansive running time. But under the detail-oriented direction of ERS founder John Collins, Fitzgerald’s famously difficult-to-translate novel often sings onstage.

Can’t top this text

Textual fidelity plays a part in the piece’s success. The production hardly includes a word not culled from Fitzgerald’s text, and the author’s graceful, swelling prose blooms with a theatricality all its own. I often found myself in awe of his descriptive insight, at once poetic and precise. Consider how Jordan Baker describes the sweat-sodden days before air conditioning became commonplace: “I love New York on summer afternoons when everyone’s away. There’s something very sensuous about it — overripe, as if all sorts of funny fruits were going to fall into your hands.”

Nothing will top that, so why try? ERS instead frames its storytelling around the sense of discovery that comes when you lose yourself in the world of a book. Page after page, your surroundings fade away, as the characters in print start to seem more real than the flesh-and-blood people sitting beside you.

A novel on the clock

In this case, a group of office workers evokes West Egg in the Roaring Twenties. They ditch their drab surroundings (rendered by set designer Louisa Thompson, with harsh, industrial lighting by Mark Barton) to escape into a world of fast cars, silk shirts, and coupe glasses overflowing with ice-cold champagne.

The office setting contains the most and least successful elements of the work. The overstatement with which ERS presents menial toil — the actors, in their nondescript button-down shirts, pressed khakis, and pencil skirts resemble walking zombies waiting to be revived — seems vaguely condescending and somewhat divorced from reality. I’ve worked my share of drudgery-filled desk jobs in the past, and I can’t remember a time when I was free to indulge in hours of reading a great American novel on the clock.

A miraculous suspension

Yet the ways in which the grey walls and windowless din fade into near-bacchanalian exuberance can be nothing short of miraculous. (Theater is about suspension of disbelief, after all, and ERS acutely understands that.) The raucous afternoon party hosted by Tom Buchanan and Myrtle Wilson at their love-nest, punctuated by flying reams of printer paper and a cacophony of overlapping voices, resembles the most fantastical daydream you could ever hope to experience. The firm pivot back to reality at its conclusion — who’s going to clean up all that detritus? — captures the harsh limits of reverie.

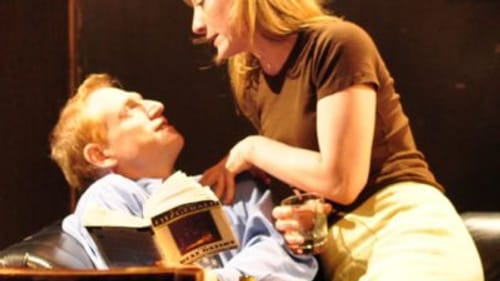

Cast of Gatz

The extraordinary stagecraft also exposes the aspects that work less well. Tonal issues persist throughout the expanse of the work, as quiet, introspective moments give way to near-slapstick stretches of physical comedy. Ben Williams’s intrusive sound design often perplexed me: what’s with all the anachronistic marimba and Muzak? At other points, romantic swells underscore moments too baldly, in ways that verge on the satirical.

These issues breed down into the performances. Robert Cucuzza’s portrayal of Tom as a barrel-chested bully makes sense, but Annie McNamara’s colorless, petulant Daisy reinforces the worst aspects of the character’s personality. Conversely, April Matthis seems overly self-conscious for gregarious, confident Jordan, and Aaron Landsman’s George Wilson drowns in understatement.

Jim Fletcher takes an intriguingly low-key approach to Gatsby, one that’s successful in its own way but underscores a gnawing question at the center of this adaptation. Surprisingly, ERS doesn’t offer much commentary on the novel’s main themes — the ideas of reinvention, personhood, and the American bootstrapping ethic. Gatsby represent all of these at their most beguiling and most dangerous. I wanted more definition in Fletcher’s transformation from dull office manager to the mercurial playboy.

Moment by moment

But questions of what ERS could have done fade away when the narrative centers around Scott Shepherd, who serves as reader, narrator, and Nick Carraway. A steady, hypnotic presence throughout, he dominates the final hour, laying down the book and reciting the concluding chapter from memory. But it never feels like rote repetition — Shepherd discovers the language, moment to moment, just as we do when we encounter an engrossing new book for the first time.

Even if you haven’t considered The Great Gatsby since high-school English class, you can probably summon its final line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Don’t be surprised if Shepherd’s unadorned delivery still takes your breath away.

What, When, Where

Gatz. Created by Elevator Repair Service, directed by John Collins. February 15 through 17, 2019, at McCarter Theatre Center, 91 University Place, Princeton, New Jersey. (609) 258-2787 or mccarter.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Cameron Kelsall

Cameron Kelsall