Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

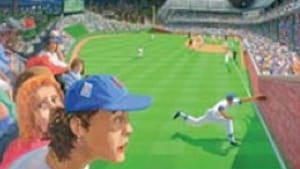

Max Mason's 'Baseball' at Gross-McCleaf

Playing the game

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

There is a reason why baseball, and not football or basketball, will always be America’s national pastime. Baseball enjoys a history as an institution, and every city lucky enough to have been in the game from the start has teams with more than a century of dreams and nightmares attached to their names. Baseball has been around long enough to have accumulated its own political, social, and economic history. It also possesses a coterie of “court painters” who record its highs and lows as assiduously as John Singer Sargent once recorded the social lions and lionesses of the Gilded Age.

Max Mason has been painting baseball images for a while now. I didn’t much care for his earlier work because it seemed too sculpted, too lifeless. It seemed more about capturing poses—like a good baseball card—rather than emotions. All that has changed with his latest show, which is heavily invested in the game’s history.

Granted, it’s more recent history than past—but then, why should Bartman’s eager hands or Schilling’s bloody sock be any less worthy of commemoration than the Black Sox or Ty Cobb’s well-filed spikes?

The Gross-McCleaf show falls quite naturally into two parts. In the rear exhibition space there are mostly large oil paintings depicting Mason’s idiosyncratic history of the game. The front exhibit area offers about 20 pastels and small oil paintings, mostly created during the Phillies’ spring training camp. These aspire toward visual journalism, and I can only wish that Mason had a looser, sketchier style. As is, there is no sense of urgency conveyed, and the images’ contents lack the gravity that Mason’s heavy style imposes upon them.

I must say that I’m still less than taken with the heaviness of Mason’s brushwork, which makes everything look lumpy rather than fluid. Safe, which is easily the most dynamic piece in the show, depicts motion, but it is an arrested motion. Even the player sliding in amid a spray of dirt looks like part of a sculptural grouping. But Mason has at least counterbalanced that “earthbound” element of his art with a fine sense of humorous fantasy in some of his larger pieces. For instance, Hell Freezes Over, his valentine to the Boston Red Sox, literally has Hell freezing around Yankee Stadium. It may not be Edvard Munch, but it’ll do.

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

There is a reason why baseball, and not football or basketball, will always be America’s national pastime. Baseball enjoys a history as an institution, and every city lucky enough to have been in the game from the start has teams with more than a century of dreams and nightmares attached to their names. Baseball has been around long enough to have accumulated its own political, social, and economic history. It also possesses a coterie of “court painters” who record its highs and lows as assiduously as John Singer Sargent once recorded the social lions and lionesses of the Gilded Age.

Max Mason has been painting baseball images for a while now. I didn’t much care for his earlier work because it seemed too sculpted, too lifeless. It seemed more about capturing poses—like a good baseball card—rather than emotions. All that has changed with his latest show, which is heavily invested in the game’s history.

Granted, it’s more recent history than past—but then, why should Bartman’s eager hands or Schilling’s bloody sock be any less worthy of commemoration than the Black Sox or Ty Cobb’s well-filed spikes?

The Gross-McCleaf show falls quite naturally into two parts. In the rear exhibition space there are mostly large oil paintings depicting Mason’s idiosyncratic history of the game. The front exhibit area offers about 20 pastels and small oil paintings, mostly created during the Phillies’ spring training camp. These aspire toward visual journalism, and I can only wish that Mason had a looser, sketchier style. As is, there is no sense of urgency conveyed, and the images’ contents lack the gravity that Mason’s heavy style imposes upon them.

I must say that I’m still less than taken with the heaviness of Mason’s brushwork, which makes everything look lumpy rather than fluid. Safe, which is easily the most dynamic piece in the show, depicts motion, but it is an arrested motion. Even the player sliding in amid a spray of dirt looks like part of a sculptural grouping. But Mason has at least counterbalanced that “earthbound” element of his art with a fine sense of humorous fantasy in some of his larger pieces. For instance, Hell Freezes Over, his valentine to the Boston Red Sox, literally has Hell freezing around Yankee Stadium. It may not be Edvard Munch, but it’ll do.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.