Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

War among artists, and artists at war

"Matisse: 1913-1917' at MOMA in New York

A single one of Matisse's boldly drawn, color-saturated paintings can seem like an entire exhibition on its own. The current show at the Museum of Modern Art, covering 1913 to 1917, offers a wealth of rich, complex works that fit this category.

Major paintings of artistic and personal significance anchor almost every gallery, with plenty of drawings, prints and sculpture to expand the story of these important years in art, European history, and in Matisse's life. The show puts the viewer at the artist's side as he responds and innovates during this period of great change. It's a profoundly satisfying experience, both aesthetically and historically.

The dates cited in the exhibition title refer to the years between Matisse's return from Morocco and his departure for Nice, and include both the onset of a terrible war in Europe and the new artistic challenges thrown down by Picasso and Cubism. The show actually covers a wider period.

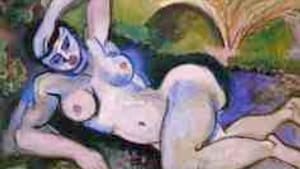

We get our first glimpse of Matisse deep in conversation with process, color and form in Blue Nude (1907), one of the show's most compelling works. Like the sculpture on which it is based (displayed nearby), the figure is lumpy and awkward, with a distended arm and oddly folded legs. The breast balls that make the nude decidedly female seem at odds with the ambiguous mask-like face. But Matisse's bold lines and his plummy blues, pinks, purples and dashes of pattern give the painting a shimmer of modern energy that's far more stirring than simple perfection.

How a painting evolved

The show's largest works are among the best known, including the sculptures of the Backs from MOMA's collection (usually seen together in MOMA's garden"“ it's interesting to be able to experience them as separate panels) and the mural-like Bathers by a River, from Chicago. A video provides an understanding of how this great painting evolved over a period of about seven years, as Matisse worked and reworked the four standing figures and the background. The end result, achieved in 1916, seems to contain a response to the awful events of World War I: The figures on the left exist in a leafy living forest, but on the right the figures stand frozen, rigid as columns against blocks of gray and black nothingness. It's a beautiful painting, albeit with a chilling undertone.

During the years spotlighted by this exhibition, Matisse confronted the ideas of Cubism, especially the emphasis on form and monochromatic color. At this time he had a Paris studio on the Quai St. Michel from which he could look out onto the Seine and the towers of Notre Dame. His abstracted view with skeleton towers of the cathedral is one of the highlights of the MOMA collection, as is The Blue Window, with its geometric forms and myriad shades of blue, the monochrome of Matisse's choice. Both paintings hold important places here.

But so do less familiar works, such as the soulful Interior with Goldfish from the Pompidou in Paris. The moody space is bereft of human presence; only a bowl of goldfish and a vase of branches witness the scene out the window, where a bit of pink, orange and green hint at continuing life.

Taking chances

One of the show's most powerful paintings is the Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914), on loan from Philadelphia. There's nothing else quite like this forceful testament to Matisse's willingness to take chances and innovate. The only color is found in two nearly random streaks of bright green; the rest is shades of grey, and the face is a blank mask with black holes for eyes.

Even more startling, the figure sprouts great looping plumes, like wings or sprays of water, from various places on her body. These lines, which Matisse called "lines of construction," were scratched into the paint, giving the surface a textured interest and freedom of movement that may, for him, have equated the satisfaction of brighter color.

The show also includes many drawings and prints, in which the delicacy of Matisse's line makes for an engaging counterpoint to his larger works. Especially poignant is the series of small sketches Matisse made of available friends during the war, hoping to use the proceeds to aid French war refugees. Seeing the faces of wives of artists who were away fighting reminds us of the import of these years and their very real impact on art and artists.

Major paintings of artistic and personal significance anchor almost every gallery, with plenty of drawings, prints and sculpture to expand the story of these important years in art, European history, and in Matisse's life. The show puts the viewer at the artist's side as he responds and innovates during this period of great change. It's a profoundly satisfying experience, both aesthetically and historically.

The dates cited in the exhibition title refer to the years between Matisse's return from Morocco and his departure for Nice, and include both the onset of a terrible war in Europe and the new artistic challenges thrown down by Picasso and Cubism. The show actually covers a wider period.

We get our first glimpse of Matisse deep in conversation with process, color and form in Blue Nude (1907), one of the show's most compelling works. Like the sculpture on which it is based (displayed nearby), the figure is lumpy and awkward, with a distended arm and oddly folded legs. The breast balls that make the nude decidedly female seem at odds with the ambiguous mask-like face. But Matisse's bold lines and his plummy blues, pinks, purples and dashes of pattern give the painting a shimmer of modern energy that's far more stirring than simple perfection.

How a painting evolved

The show's largest works are among the best known, including the sculptures of the Backs from MOMA's collection (usually seen together in MOMA's garden"“ it's interesting to be able to experience them as separate panels) and the mural-like Bathers by a River, from Chicago. A video provides an understanding of how this great painting evolved over a period of about seven years, as Matisse worked and reworked the four standing figures and the background. The end result, achieved in 1916, seems to contain a response to the awful events of World War I: The figures on the left exist in a leafy living forest, but on the right the figures stand frozen, rigid as columns against blocks of gray and black nothingness. It's a beautiful painting, albeit with a chilling undertone.

During the years spotlighted by this exhibition, Matisse confronted the ideas of Cubism, especially the emphasis on form and monochromatic color. At this time he had a Paris studio on the Quai St. Michel from which he could look out onto the Seine and the towers of Notre Dame. His abstracted view with skeleton towers of the cathedral is one of the highlights of the MOMA collection, as is The Blue Window, with its geometric forms and myriad shades of blue, the monochrome of Matisse's choice. Both paintings hold important places here.

But so do less familiar works, such as the soulful Interior with Goldfish from the Pompidou in Paris. The moody space is bereft of human presence; only a bowl of goldfish and a vase of branches witness the scene out the window, where a bit of pink, orange and green hint at continuing life.

Taking chances

One of the show's most powerful paintings is the Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914), on loan from Philadelphia. There's nothing else quite like this forceful testament to Matisse's willingness to take chances and innovate. The only color is found in two nearly random streaks of bright green; the rest is shades of grey, and the face is a blank mask with black holes for eyes.

Even more startling, the figure sprouts great looping plumes, like wings or sprays of water, from various places on her body. These lines, which Matisse called "lines of construction," were scratched into the paint, giving the surface a textured interest and freedom of movement that may, for him, have equated the satisfaction of brighter color.

The show also includes many drawings and prints, in which the delicacy of Matisse's line makes for an engaging counterpoint to his larger works. Especially poignant is the series of small sketches Matisse made of available friends during the war, hoping to use the proceeds to aid French war refugees. Seeing the faces of wives of artists who were away fighting reminds us of the import of these years and their very real impact on art and artists.

What, When, Where

“Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917.†Through October 11, 2010 at Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd St., New York. (212) 708-9400 or www.moma.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Marilyn MacGregor

Marilyn MacGregor