Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

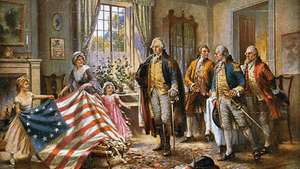

Betsy Ross, defense contractor

Marla R. Miller's biography 'Betsy Ross and the Making of America'

Marla R. Miller’s Betsy Ross and the Making of America is the first attempt to present an accurate, thoroughly researched portrait of a Philadelphia icon. It could have been a debunking book but turned into something much more valuable.

Miller adapts a strategy many use when writing biographies about poorly documented lives. She tells us what it was like to be that kind of person during that period. The result is a portrait of the men and women who could truly claim they built Philadelphia — the hard working artisans who created the buildings, furniture, clothing, and other physical necessities that supported a thriving society.

Widows and working women

We’re usually told Betsy was a “seamstress,” a term that implies, to most of us, that she made dresses. She was, in fact, an upholsterer. In addition to making pillows and furniture covers, upholsterers made bed curtains, window drapes, Venetian blinds, and rugs. Many upholsterers made military items like drum covers and flags. In her later years, Betsy and her husband hung wallpaper when that became popular.

The working woman and the two-income family have a long history. Betsy Griscom was a carpenter’s daughter who met her first husband, John Ross, during the years they were both apprenticed to an upholsterer. They went into business together and when he died prematurely, the widow kept up the business. Her second husband was a mariner who was captured by the British during the revolution. Her third husband was a mariner who survived the war and worked with her in the shop before he became a federal customs agent during John Adams’s administration. She was Mrs. Elizabeth Claypoole for most of her life, but the author calls her Betsy throughout the book, to distinguish her from all the other Elizabeths in her family.

Most of Betsy’s extensive roster of sisters, daughters, nieces, and granddaughters were working women. Widowhood was all too common, and a widow without a trade became dependent on the charity of her family.

Battles for the soul

Miller’s chapters on the revolution present a vivid portrait of the pressures it imposed on Betsy’s class. It’s easy to forget that the revolution was a civil war. Patriots repressed the opposition to independence with mob violence and cruelties such as tarring and feathering. Betsy and her husband supported independence, but upholsterers were caught in a crossfire during the boycotts that preceded the war; their output may have been made in America but they depended on imported fabrics.

Miller’s passages on Quaker excommunication were a surprise to this reader. The Quaker tolerance of other faiths didn’t mean William Penn’s brethren tolerated dissention in their own ranks. Quaker meetings “disowned” members who violated their doctrinal and behavioral standards. Betsy was disowned when she married John Ross, who was an Anglican. In her middle years, she joined a group of disowned Quakers who called themselves Free Quakers and founded their own meeting.

About that flag

Betsy Griscom Ross Ashburn Claypoole probably didn’t live in the Philadelphia tourist attraction that bears her name, but she did live on that block of Arch Street, in a house like it. She probably didn’t make the first American flag, but she made a lot of flags. We don’t have solid records of her activities during the revolution because war department records were lost during a fire in 1800, but “…there is no doubt whatsoever,” Miller writes, that she was one of “Philadelphia’s most important flag makers.” During the first decade of the 19th century, a period for which we have good federal records, her shop produced dozens of flags and standards. At the beginning of the War of 1812, she was “the primary flag maker contracting with the U.S. arsenal on the Schuylkill River.”

Did she really show George Washington that the flag should be decorated with five-pointed stars because five-pointed stars could be cut with a single snip? We don’t know. The story first gained attention in 1870 when her grandson included it in a speech and claimed it was family lore, passed on by relatives who’d heard it from Betsy herself.

But it could have happened. Something like it may have happened. Betsy Ross acquired connections that could have put her in touch with George Washington. As Miller notes, she was a contractor seeking an order from the head of the American military forces. When she created a star with one snip, she was demonstrating an efficient, cost-effective production method.

The Betsy Ross of national legend is a one-dimensional figure whose fame rests on a single event and a national obsession with historic firsts. The Betsy Ross depicted in this book is a real woman who coped with the tensions of a small business and kept it going through war, political upheaval, two yellow fever epidemics, and all the pleasures and trials of a complicated family life.

What, When, Where

Betsy Ross and the Making of America. By Marla R. Miller. Henry Holt and Co., 2010. 467 pages, paperback; $5.15, available at amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom