Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The man who lacked a center

Man Ray: The undefined artist (in New York)

A 1999 survey placed the Philadelphia-born Man Ray among the 20th Century's 25 most influential artists. That puts him in elite company indeed. Yet Ray, certainly a major figure in the Paris avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s, was gradually forgotten over the last 35 years of his life, which ended in 1976. And having long walked, as he put it, "between the chasms of notoriety and oblivion," he feared himself condemned at last to the latter.

Ray was candid about his desire for enduring fame; yet he began his career with an act of self-obliteration. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky to Russian immigrants, he shortened his childhood diminutive of "Manny" to "Man" after his parents dropped the middle six letters of the family name.

The result was a professional name that, consisting of two abstract nouns, suggested an amphibian identity— a creature partly subsisting in the rational element of terra firma and partly in the marine element of the dream. This led him naturally in the direction of Dada and Surrealism, of which he was, with Marcel Duchamp and Tristan Tzara, an early practitioner.

More significantly, Ray abjured his Jewish heritage entirely, acknowledging it only when Hitler forced him to flee France. Fame creates an identity, but it also requires one; and in going beyond assimilation to deracination, Ray became a kind of changeling, moving rapidly from style to style and medium to medium.

Unlike Picasso

Although he created some of the 20th Century's most iconic images— the spiked iron of Gift, the clef-signatured female back of Le Violin d'Ingres, the detached, floating lips of Observatory Time, the Lovers— he never seemed centered as even so Protean an artist as Picasso always does.

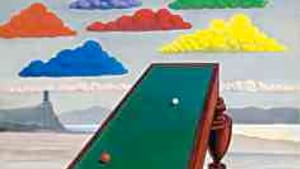

Ray considered himself foremost a painter, but that may have been the least of his gifts. His colors are bold but rarely vivid or subtle, and too often he suggests someone else— Dali in La fortune, Magritte in La rue Ferou.

He was far better known as a portrait photographer in his early Paris days— when, as Sylvia Beach remarked, "To be done by Ray was to be somebody"— and for his experiments with emulsified light. He was at his best when Lee Miller served as his muse, lover and assistant between 1929 and 1932, and it's regrettable that Lee was mostly represented in the Jewish Museum's just-concluded and otherwise comprehensive retrospective mainly by his embittered response when she left him to pursue her own career (though it's her— uncredited— torso that streaks of voltage play across in one of the images for his commissioned series on electricity).

Ray found no shortage of female models afterward, but none who inspired him as Lee did, and certainly none who brought out such raw and uncensored emotion in him.

His case for recognition

Ray was also an experimental filmmaker, and he himself was the subject of a late documentary in which, a pixified Zelig with a South Philly accent, he ruminates on his legacy. "In 60 years you can do a lot of work," he observes, both stating and retracting the case for posthumous recognition.

Fame is the wish to be known, after all; but to be known is to be revealed, an even deeper wish and fear. Ray never resolved this tension, either in his life or his art; and what he finally settled on was an eloquent shrug: "Unconcerned," as he put it, "but not indifferent." It is the phrase that is inscribed on his tombstone.♦

To read a response, click here.

Ray was candid about his desire for enduring fame; yet he began his career with an act of self-obliteration. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky to Russian immigrants, he shortened his childhood diminutive of "Manny" to "Man" after his parents dropped the middle six letters of the family name.

The result was a professional name that, consisting of two abstract nouns, suggested an amphibian identity— a creature partly subsisting in the rational element of terra firma and partly in the marine element of the dream. This led him naturally in the direction of Dada and Surrealism, of which he was, with Marcel Duchamp and Tristan Tzara, an early practitioner.

More significantly, Ray abjured his Jewish heritage entirely, acknowledging it only when Hitler forced him to flee France. Fame creates an identity, but it also requires one; and in going beyond assimilation to deracination, Ray became a kind of changeling, moving rapidly from style to style and medium to medium.

Unlike Picasso

Although he created some of the 20th Century's most iconic images— the spiked iron of Gift, the clef-signatured female back of Le Violin d'Ingres, the detached, floating lips of Observatory Time, the Lovers— he never seemed centered as even so Protean an artist as Picasso always does.

Ray considered himself foremost a painter, but that may have been the least of his gifts. His colors are bold but rarely vivid or subtle, and too often he suggests someone else— Dali in La fortune, Magritte in La rue Ferou.

He was far better known as a portrait photographer in his early Paris days— when, as Sylvia Beach remarked, "To be done by Ray was to be somebody"— and for his experiments with emulsified light. He was at his best when Lee Miller served as his muse, lover and assistant between 1929 and 1932, and it's regrettable that Lee was mostly represented in the Jewish Museum's just-concluded and otherwise comprehensive retrospective mainly by his embittered response when she left him to pursue her own career (though it's her— uncredited— torso that streaks of voltage play across in one of the images for his commissioned series on electricity).

Ray found no shortage of female models afterward, but none who inspired him as Lee did, and certainly none who brought out such raw and uncensored emotion in him.

His case for recognition

Ray was also an experimental filmmaker, and he himself was the subject of a late documentary in which, a pixified Zelig with a South Philly accent, he ruminates on his legacy. "In 60 years you can do a lot of work," he observes, both stating and retracting the case for posthumous recognition.

Fame is the wish to be known, after all; but to be known is to be revealed, an even deeper wish and fear. Ray never resolved this tension, either in his life or his art; and what he finally settled on was an eloquent shrug: "Unconcerned," as he put it, "but not indifferent." It is the phrase that is inscribed on his tombstone.♦

To read a response, click here.

What, When, Where

“Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention.†Ended March 14, 2010 at the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Ave., New York. (212) 423-3200 or www.thejewishmuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller