Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

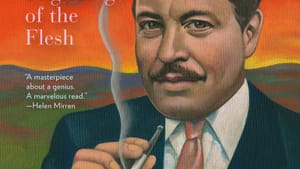

Rethinking the life and work of Tennessee Williams

John Lahr's biography of Tennessee Williams

- "Everything in [Tennessee Williams’s] life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is in his life." ~ Elia Kazan

- “We’re all of us living in a house we’re not used to. . .a house full of — voices, noises, objects, strange shadows, light that’s even stranger —. . .Then it gets to be dark.” ~ Chris Flanders in Tennessee Williams’s Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore.

Tennessee Williams was the most prolific and successful American dramatist of the 20th century. His legacy of Broadway productions, most of which were made into films, is stunning. The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Rose Tattoo, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Orpheus Descending, Summer and Smoke, Sweet Bird of Youth, El Camino Real, and The Night of the Iguana stand out as depth probes of the dark and fragile side of human life, always with a narrow hope for redemption.

Inwardly, as a result of a brutal childhood, Williams was a holy mess of sexual compulsivity, nameless dread, misguided relationships, and progressive drug and alcohol addiction. Donald Spoto’s Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams (Da Capo Press, 1997) covered the warp and woof of his life. Now, John Lahr’s new biography of Williams, fueled by a wealth of documents he obtained from the Williams estate, provides a forensic dissection of the relationship between Williams’s traumatic life and the construction of his plays. It raises new questions about Williams’s personality and the way he constructed his dramas and realized them on stage and in film.

The devil is in the details

Don’t let Lahr fool you with his chatty, gossipy prose. Like the recent Ferguson grand jury, he has made a “document dump” of countless letters, memoirs, interviews, news items, and anecdotes into a reconstructed telling of events. It is left to readers whether to “indict” Williams as a sadomasochistic, over-sexed, impulsive, self-aggrandizing human being or to exonerate him as a great playwright who raised human consciousness to new levels of sensitivity and vulnerability.

Probably both vantage points are correct, which constitutes the essential paradox of his life. Whatever the ultimate judgment of Williams’s character and artistic purpose, the details Lahr provides of his family, daily rounds, changes of habitat (addiction counselors call them “geographical cures”), beleaguered friendships, theatrical productions, and offstage comments, poems, and stories offer the most extensive and intimate glimpse yet into the connections between Williams and his work.

Rarely do we see in a biography such a detailed and constant crossover between life and creative ferment as we do here. Lahr conveys both Williams’s unfolding life story and his creative process like the two helical strands of DNA, always linking one to the other. Like the repeating amino acid sequences of DNA, we see Williams’s intimate relationships, bouts of malaise, theatrical productions, and interactions with collaborators, producers, and actors recurring in combinations and permutations across a life trajectory. One of the most important of these relationships is the one with legendary director Elia Kazan, who at times came close to being a cowriter of his scripts.

Lahr, the longtime drama critic for the New Yorker, who also is the son of the comedian Bert Lahr, creates theater of his own as he details scene after scene of events in Williams’s life, attempting the difficult task of implanting himself in the mind of his subject to see what made him tick. Lahr concludes, with some justification, that what made Williams tick was the “mad pilgrimage of the flesh.”

Lahr, the longtime drama critic for the New Yorker, who also is the son of the comedian Bert Lahr, creates theater of his own as he details scene after scene of events in Williams’s life, attempting the difficult task of implanting himself in the mind of his subject to see what made him tick. Lahr concludes, with some justification, that what made Williams tick was the “mad pilgrimage of the flesh.”

After enduring youthful austerity, Williams sought relief from his suffering through chaotic sexual liaisons and cravings for admiration, alcohol, and drugs. Yet, at his best, he was able to use his inner conflicts to create dramatic works that transformed the American theater and cinema. The characters in his plays, as Lahr takes pains to show, were mirrors of what was going on inside him.

The demons of the family and the flesh

While Williams’s plays are dominated by the delusional fecklessness of his characters, what controlled his psyche was an internalization of his traumatic family history within his own body. His family background was characterized by his grandfather’s larger-than-life personality; his father’s domineering, sometimes violent, and abandoning mistreatment of everyone; his mother’s spartan outlook; and his beloved sister’s journey into madness and a lobotomy treatment that took away her soul along with her mental symptoms. In response to the misery that surrounded him, and because of his acute sensitivity and emotionality, Williams experienced unremitting bouts of hedonism and pain that haunted him like demons.

His way of surviving this inner hell tells us something profound about the creative process. He took his tortured body and mind as mirrors of the human condition and wellsprings of dramatic dialogues. It’s the leap that Freud called sublimation, and in Williams’s case, it provided a tonic for his neurosis that brought a degree of meaning and purpose out of the entropic chaos, the death instinct that was always eyeing him from his unconscious.

A psychoanalysis gone awry

Williams poured himself into his work and turned to sex and alcohol as ways of coping with his inner turmoil, but when those solutions didn’t work, he sought treatment. Lahr documents Williams’s consultation with the renowned psychoanalyst Lawrence Kubie, who wrote a book about creativity and treated celebrities like Leonard Bernstein, William Inge, Josh Logan, and Vladimir Horowitz. Through Kubie’s intervention, Williams gained temporary control over his alcoholism, but little else.

The fact that the treatment with Kubie is the dullest episode in the whole volume suggests something about the vanity of trying to lasso the instincts like a wild horse. Kubie simply ordered Williams to stop drinking, writing, and having sex until he could gain insight into his problems. Of course, Williams couldn’t or wouldn’t comply, and the supposed analysis became a cat and mouse game with some feigned progress that later dissolved.

Control freak or tragic figure?

The ultimate question that is raised by Lahr’s detailed accountings of Williams’s life is whether he was a manipulative sociopath whose success meant more to him than any authentic moral values or he was driven by irresistible inner impulses to violate his own good intentions. His personality seemed to oscillate between cunning control to attain his own ends — whether the success of a play or turning a partner into a sex object or a housekeeper — versus an attitude of compassion furthered by guilt and remorse, manifested, for example, in providing for the care of his lobotomized sister and helping his estranged lover Frank Merlo through the end-stages of cancer.

Lahr is careful to present the facts and details without drawing hard and fast conclusions about Williams’s stance toward the world. But the answer seeps through the pages of this book. Williams was a fragile and vulnerable person always in danger of falling apart or destroying himself. He couldn’t control his streetcar of desire, so to regain his fragile self-esteem, he controlled others and demanded success. Finally, he could control no one and produce no new successes. He was a tragic figure, a bit like Hamlet and Lear, and a lot like the characters who inhabit his own plays.

Above right: Andy Warhol and Tennessee Williams talking on the SS France; in the background: Paul Morrissey. (Photo by James Kavallines; public domain.)

What, When, Where

Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh. By John Lahr. New York: W.W. Norton, 2014. Available on Amazon.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Victor L. Schermer

Victor L. Schermer