Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Johnny Broom and Marion Morrison

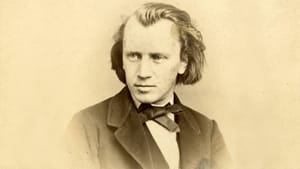

Johannes Brahms and John Wayne

Long hospitalizations make for strange literary bedfellows. I recently spent over four and a half months in hospitals and rehab centers after getting knocked over by a bicyclist on the Schuylkill Trail. By the end of the fourth month, I was ready to read anything — anything — that would hold my attention.

For some people, the distraction of choice is thrillers. For me, it’s biography and narrative history. I read Jan Swafford’s biography of Johannes Brahms because guitarist Alan Krantz recommended it. I followed it with Scott Eyman’s John Wayne bio because the reviews intrigued me, ever though I’ve never been a John Wayne fan. For me, John Wayne was something of a joke. When I went through basic training in 1959, the sergeants had a phrase for actions that were so absurdly heroic no one in his right mind would try them. They called it “pulling a John Wayne.”

Unexpected commonalities

Oddly enough, though, the 19th-century German composer and the 20th-century American movie star had a few things in common. For one thing, they both had fathers who were poor providers. Brahms was the son of a freelance bass player — a “beer fiddler” in the local argot. When he was 13, Brahms supplemented his family income by playing the piano in whorehouses every night. Wayne’s father was the kind of man who failed at a number of enterprises, not finding a slot until long after his son reached maturity.  Wayne did the kinds of jobs American kids do and went to USC on a football scholarship (which he lost when he was injured).

Wayne did the kinds of jobs American kids do and went to USC on a football scholarship (which he lost when he was injured).

Both of them had problems relating to women. Brahms’s adolescent piano gigs seem to have produced a classic example of a male with the madonna-whore syndrome. Throughout his life, he engaged in a number of nonsexual romantic relationships with women musicians, the most famous being his long relationship with Clara Schumann. For sex, he turned to prostitutes.

Wayne’s weakness was his obtuseness as a wife picker. He had three marriages, none of them satisfactory. Outside of marriage, he seems to have had affairs with most of his leading ladies, including Marlene Dietrich.

Paths to success

Brahms’s life reads like a fantasy for those who dream of a career in the arts. Brahms managed to make a living as a composer and pianist from the time he was 20, earning much of his income from a series of songs composed, throughout his life, for middle-class Germans who liked to sing and play music in their homes.

John Wayne’s career path was more convoluted, but he never had to work as a waiter. At 23, he was chosen for the lead role in an epic Western, The Big Trail, and touted as a new star. The movie flopped, and Wayne spent the next eight years making B-pictures — 81 of them. Then John Ford tapped him for Stagecoach, and he stayed on top for the rest of his life.

The man and the mask

John Wayne’s most interesting relationship was the one he had with John Wayne. He was born Marion Morrison, and he acquired the nickname “Duke” when he was a boy. Many of his fans took to calling him “The Duke” in his later life, but he maintained that he thought of himself as plain Duke Morrison.

“That guy you see on the screen isn’t really me,” Wayne said. “I’m Duke Morrison, and I never was and never will be a film personality like John Wayne. I know him well. I’m one of his closest students. I have to be. I make a living out of him.”

When his doctor told him he had lung cancer, he said he sat there “wishing I was John Wayne.”

Swafford notes that Brahms’s name could be translated as Johnny Broom — a good name for a saloon pianist. Brahms composed under his own name, but he adapted a personal alter ego, Young Kreisler, taken from a romantic hero in the stories of E.T.A. Hoffmann. He protected his privacy in other ways as well: In his later years, he burned many of the letters friends had sent him and asked them to return his letters so he could burn those, too. The face he presented to posterity was intended to be a construct, just like John Wayne.

“The chief consideration, in the selection of material for a biography of an artist or author,” Brahms wrote a potential biographer, “should be whether the facts in question were of a nature to make the artist, whom we love and honor in his art, also win our esteem as a man.”

Man, artist, worker

Biographers of artists and performers often concentrate on their subject’s private lives, which can leave readers with a distorted picture of how these hardworking people really spent their days. Both of these authors avoid that temptation. Swafford delves into musical technicalities, which, he cheerfully advises readers, they can skip if they prefer. Even if you just skim those sections, though, you will still get a sense of the things the composer thought about during the most important hours of his life.

John Wayne made two or three movies a year and may have been happiest when he was working. Eyman creates a portrait of an expert craftsman who had studied every aspect of the movie business. Each of Wayne’s trademark hesitations, for example, earned him an extra two or three seconds of screen time.

You can listen to Brahms’s music without knowing he could be nasty to his friends and spent much of his leisure time sitting in cafés listening to gypsy music. You can watch Rio Lobo or True Grit without knowing John Wayne was an avid chess player and his third wife played tennis while he was traveling the world earning the money that supported three families. If you find stuff like that interesting, these books will give you some insight into the very human process that produces the creations we discuss in journals like the Broad Street Review. You don’t even have to read them together.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom