Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Kitty Foyle and yellow fever, set to music?

In search of Philadelphia operas

Opera Philadelphia, once a cautious and financially shaky purveyor of reliable old chestnuts unlikely to disturb anyone in its graying Main Line audience, last week announced a gutsy (and apparently fully funded) $10 million plan to kickstart its season each fall with a 12-day festival of edgy productions that could draw tens of thousands of bingeing East Coast opera junkies of all ages.

In the past, the Academy of Music — America’s oldest and most elegant opera house, what Luciano Pavarotti called “this marvelous place to sing” — was the Philadelphia magnet that drew audiences to hear the likes of Caruso, Marian Anderson, Adelina Patti, Renata Scotto, and of course Pavarotti himself, who chose Philadelphia out of all the world’s cities as the venue for his Pavarotti International Voice Competition in the 1980s. (That competition foundered, among other reasons, on the great tenor’s reluctance to disappoint any young singers by picking winners and losers.) But the new O Festival, as it’s called, will draw audiences not just to the Academy but also to other less likely local venues.

The first festival, scheduled for September 2017, will offer six new operas “relevant to a 21st-Century audience,” as the company’s chairman, Daniel K. Meyer, characterized them. There’s not a Verdi or a Puccini in the lineup. The menu includes Barrie Kosky’s playfully subversive multimedia Berlin production of Mozart’s Magic Flute at the Academy (with a free HD video broadcast on Independence Mall); Elizabeth Cree by Kevit Puts at the Kimmel Center; Daniel Bernard Roumain’s hip-hop We Shall Not Be Moved at the Wilma Theater; a war-related double-bill teaming Monteverdi’s 1638 work Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda with Lembit Beecher’s recent I Have No Stories to Tell You at the Art Museum; a recital by the soprano Sondra Radvanovsky at the Kimmel; a world premiere commissioned by Opera Philadelphia; and a yet to be announced art-related opera at the Barnes Foundation. All told, the festival’s 25 performances could draw as many as 35,000 people to Philadelphia, including perhaps 15,000 to the free Magic Flute broadcast on Independence Mall.

Seville's status

This development, it goes without saying, is wonderful — even astonishing — news. It suggests that Opera Philadelphia has developed the confidence to lead rather than follow. It suggests that local opera devotees need not head for New York to find opera’s cutting edge. It suggests that Philadelphians possess the imagination and coordination to exploit their unique tourist attractions as magnets to draw visitors other than papal acolytes. Perhaps most important, it suggests that the most creative days of opera — which many critics believe peaked in the 19th century — are still to come.

All of which raises one curious question: With all this operatic creativity, money, and synergy in Philadelphia, how come no one past or present has written an opera that takes place in Philadelphia?

If you Google “Operas set in Philadelphia” or “Operas about Philadelphia” you will find . . . nothing. Why have so many operas been set in a backwater like Seville (pop. 700,000) and none in the birthplace of modern democracy (pop. 1.5 million)? Why do some places seem to lend themselves to grand operatic themes while others don’t?

Buffoons vs. lunatics

Some of the answers seem obvious. Playwrights and composers head for allegedly world-beating cities like New York, London, and Paris and then write what they know. The most dramatic of all conflicts — warfare — has mercifully bypassed Philadelphia, at least since 1778. Philadelphia is the world’s only major city founded and profoundly influenced by that most conflict-averse (not to mention music-averse) religious sect, the Quakers. Our heroes tend to be lawyers and doctors, not saints and soldiers.

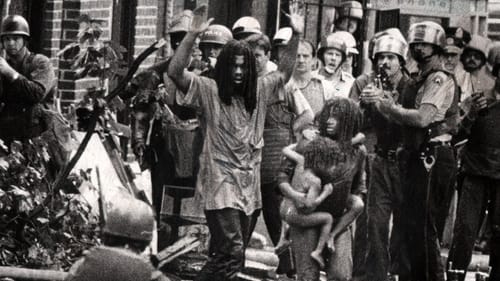

To be sure, Philadelphia’s macho former cop and mayor Frank Rizzo was the mother of all drama queens. But tales of urban politics rarely rise to the level of Verdi or Wagner. And Philadelphia’s recent operatic disasters — like the 1985 MOVE confrontation, in which a police bomb destroyed an entire city block — tend to pit buffoons against lunatics rather than heroes against villains.

Riots and epidemics

But surely some composer could fashion an opera out of the burning of Pennsylvania Hall in 1838, when an angry Philadelphia mob destroyed a new, large, handsome building dedicated to freedom of speech, racial harmony, gender equality, and the abolition of slavery. Surely some contemporary Verdi could find his Violetta in the tragic story of the department store heiress Fernanda Wanamaker, who seemingly had it all — brains, beauty, charm, and an inexhaustible checkbook— yet somehow wound up an alcoholic who tumbled to her death from her apartment balcony at age 52 in 1974. Or how about the Nativist Riots of 1844, when Protestant nativists burned the Catholic St. Augustine’s Church in Kensington, while other Protestants successfully fought off the same mobs to protect St. Patrick’s Catholic Church near Rittenhouse Square, lest a fire at St. Patrick’s spread to their own homes nearby?

A small but stubborn group of novelists has already found rich material in the Philadelphia they knew. S. Weir Mitchell’s historical novel The Red City (1909) depicted Philadelphia’s terror during its yellow fever epidemic of 1793. Christopher Morley’s Kitty Foyle (1939), a stream-of-consciousness work about the travails of a shopgirl in a class-conscious city, became an instant best-seller and then a film starring Ginger Rogers. Birdy, William Wharton’s carefully structured first novel (1978), delves into the magical mind of a working-class Philadelphia kid whose fantasies become the stuff of his actual life. Third and Indiana, by Steve Lopez (1994), similarly focused on the experiences of a 14-year-old boy in a gang-controlled neighborhood. Jennifer Weiner launched her fiction career in 2001 with Good in Bed, the story of an overweight Jewish Philadelphia journalist modeled after the author, her love and work life, and her emotional abuse issues with her father.

Racial themes

A surprising number of Philadelphia-based novels pursue racial themes. Bright April, by Marguerite de Angeli (1946), concerns a young African-American girl’s first experience with racial prejudice. Fran Ross’s 1974 satirical novel Oreo has acquired cult status. Losing Absalom, by Alexs Pate (1994), follows an African-American family's daily struggles in North Philadelphia. John Edgar Wideman’s Two Cities (1998) evokes the violence that haunts the author’s own life in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Great novels don’t necessarily make great movies or operas, of course. But take it from a journalist who was born and raised in New York and later lived in Chicago: Great human stories can be found anywhere, even in Philadelphia. All it takes is a discerning mind and a composer willing to set the tale to music. A commission from an ambitious local opera company wouldn’t hurt, either.

For Steve Cohen's look at 017, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg