Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Seeing as they saw

Delaware Art Museum presents 'Eye on Nature: Andrew Wyeth and John Ruskin'

In our era of climate change and dystopian fears, it’s riveting — and comforting — to be immersed in the Delaware Art Museum’s current major exhibition, Eye on Nature: Andrew Wyeth and John Ruskin. It’s a finely detailed exploration of the work of two seemingly disparate artists a century and a continent apart: Ruskin (1819-1900) and Wyeth (1917-2009).

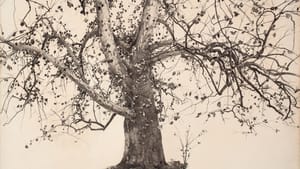

They are not obvious artistic bedfellows, and asked why she decided to pair them, curator Margaretta S. Frederick said two drawings made her do it: Ruskin’s “Trees in a Lane, Perhaps at Ambleside” (1847) and Wyeth’s “Sycamore Tree” (1941). Similar in execution and intent, the renderings drew her to explore the similarities of the two artists themselves.

Frederick contends that humans tend to categorize, but this exhibition asks that we set aside the obvious categories — chronology, artistic names, and labels — and engage our sense of sight. We should find comparisons and parallels that echo throughout the exhibition. Eye on Nature is not an exercise in knowing or classifying, but in seeing.

Two of a kind

The exhibition has four sections, each titled with the artistic credos uniting the two men: “Seeing is knowing,” “The world as they saw it,” “The importance of place,” and “Nature has the power to restore.” Each section is enhanced by words from the artists, and often — but not so often as to be predictable — works are displayed in duos, side by side. Wyeth and Ruskin, both meticulous draftsmen, used white space to highlight intimate details a casual viewer might miss, imbuing these works with meaning and even symbolism.

All the drawings are of natural-world subjects. Often, they were a first step, fragments used toward creating something else. For Wyeth, these were most often studies for his larger artworks. Ruskin, the leading Victorian art critic and author of more than 250 published works on a vast range of subjects, utilized his drawings to inform his writing.

It is sometimes difficult to determine which artist made which work. This difficulty is especially evident in Ruskin’s “Mountain Rock and Alpine Rose.” Even closely observed, it could be a Wyeth.

The men are also similar in other ways. Both were trained unconventionally and at home, not in conservatories — Wyeth by his father (illustrator N.C Wyeth) and Ruskin by tutors and art teachers. Both were profoundly influenced by place — Wyeth by Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and Maine; Ruskin by the Alps and England’s Lake District.

Both sought inspiration and solace in nature during world tumult — the Industrial Revolution, World War II. Ruskin worked in the English watercolor tradition, which directly informed Wyeth’s creations. Each looked deeply into the natural world. And both believed “winnowing down” (Wyeth’s words) was the essence of acquiring true vision.

Spare and natural

The installation design by Keith Ragone Studios is itself winnowed down. There are pale oak panels on brown or off-white walls, with narrow windows to allow tantalizing views across the room. At first glance, the open space seems spare and almost unfinished.

But in creating and mounting this subtle, thoughtful, complex, and unusual exhibition, both curator and designer have taken their cues from the artists. Ruskin says, “Nature is painting for us, day after day, pictures of infinite beauty, if only we have the eyes to see them.” And Wyeth advised “hold[ing] a mirror up to nature. Don’t overdo it, don’t underdo it.” Eye on Nature takes those axioms to heart, encouraging the viewer to slow down, exhale, and enter an experience of looking and truly seeing.

Many of these works are unlikely to be shown again in the United States. The exhibition includes 30 rare Ruskin drawings, the largest collection of his work seen in this country in 25 years and the largest-ever loan from England’s Ruskin Library. Wyeth is represented by 28 watercolors and dry brush from the museum’s holdings and from private collections, several never before exhibited.

Ruskin struggled to merge his understanding of science with his religious beliefs, so people of different faith communities narrate an unusual audio tour. The exhibition also has a helpful timeline, and the museum offers a slate of programs including nature walks, slow art tours, and workshops.

What, When, Where

Eye on Nature: Andrew Wyeth and John Ruskin. Through May 27, 2018, at the Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Parkway, Wilmington, Delaware. (866) 232-3714 or delart.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder