Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Who’s the savage?

Danai Gurira’s ‘The Convert’ at the Wilma

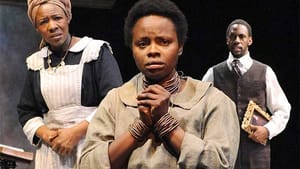

From the moment Jekesai (Nancy Moricette) appears on stage— barely clothed and vulnerable, speaking only her native language, amazed by a floor made of cement rather than cow dung— we know that we’re in for an interesting adventure through an unfamiliar culture.

But what begins as almost drawing room comedy— Eliza Doolittle as an African woman speaking Shona and Henry Higgins as a devout Christian in colonial Rhodesia— ends three hours later in an explosive confrontation of loyalties to family, to culture and to Jesus.

Playwright Danai Gurira, known to many Americans as Michonne on The Walking Dead, here tells the story of the early black insurrections against the British in the 1890s— not through the warriors but through those on the fringes who suffered and watched their love ones struggle, starve, work in the mines and die. In the process, Gurira challenges our expectations by mixing traditional narrative (she acknowledges her debt to George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion) with unexpected choices made by characters we thought we knew.

Educated woman’s dilemma

Jekesai, escaping from an unwanted marriage to an old man, is brought to the home of Chilford (Irungu Mutu), a black man who has embraced Christianity and wants to become one of Africa’s first black Jesuit priests. Her aunt, Mai Tamba (Starla Benford), a Shona woman who embraces traditional rituals and hides pagan tokens about the house, persuades Chilford to take Jekesai under his protection.

He does so, renames her Ester, and she turns into his star pupil, embracing Jesus and the Virgin Mary with a fervor that surprises even him. In the process she is forced to make choices about where her loyalties lie.

The traditional story of a savage woman transformed into an idealized female image— whether it’s Pygmalion, My Fair Lady or Pretty Woman— always leaves the woman with a dilemma. Once she has lost her original identity, she is neither one thing nor the other— neither savage nor accepted in the society around her.

Colonial mindset

“There is no place for a highly educated African woman,” says Prudence (Zainab Jah), the fiancée of Chilford’s friend Chancellor. Disowned by her family, Prudence is now isolated by her education. “There will be no one to bury me when I die,” she laments. When her fiancée dies, she must depend on the kindness of others to survive— no matter how well she speaks the Queen’s English, and no matter how smart she is (smarter than the men around her, she points out frequently).

The obvious parallels between women and the earth, women and Africa infuse the story. That women are there to serve men is woven into the colonial mindset as well as the native one. Jekesai’s uncle wants to sell her off in marriage. Chilford expects her, as Ester, to take care of the house and make sure he’s fed, although luckily for her he is practicing celibacy for his eventual acceptance into the priesthood.

Ritual and reason

Africa and the Africans are there to serve the British as well, and they must know their place. “Never correct a white man,” Chilford tells Ester. But her cousin Tamba (Joshua E. Nelson) reminds her how hard the work in the mines can be, and how the people resent having to earn money to buy food for their family that they once could grow on their own.

What’s unique is the power each of the women brings to the story. Ester believes in Jesus and wants to educate her people. Mai Tamba believes in Shona ritual; the pagan customs that she practices whenever Chilford isn’t around give her a sense of safety and a connection to family. Prudence believes that education and rational thought can help her survive.

While the men around them resort to despair and violence, these women plot a course of action. Their power resonates across the stage.

Change of tone

For the first two acts, the actors keep us engrossed as the story shifts from comedy to drama, sometimes a bit overdone, although always engaging. As Act III began, the tone changed. The actors became subdued, their voices sometimes dropping so low that they were hard to hear, yet the audience remained mesmerized, leaning forward to catch each word.

Ultimately The Convert challenges us to think about loyalties, about faith, about who is and isn’t a savage. Since Gurira sees this work as the first in a trilogy about Zimbabwean identity, there will be more to come.

What, When, Where

The Convert. By Danai Gurira; Michael John Garces directed. Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company production through November 10, 2013 at Wilma Theater, 265 S. Broad St. (at Spruce). (215) 546-7824 or www.wilmatheater.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Naomi Orwin

Naomi Orwin