Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

How to describe the indescribable?

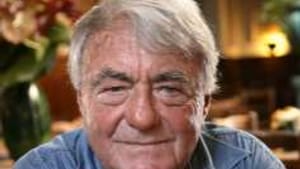

Claude Lanzmann at the Free Library

An appearance by Claude Lanzmann is special. Now in his 80s, Lanzmann is best known for Shoah, a film about the Holocaust that's one of the few artistic statements about it that is nonrebarbative. Theodor Adorno once said that poetry after Auschwitz— not just about Auschwitz itself, but about anything— was obscene, and although Adorno later regretted the statement, it has enough truth to it to stick. Civilization itself reached its nadir in the Holocaust, and silence was in a sense the only appropriate comment on it.

Of course, silence did greet the Holocaust, not only at the time but also for a generation afterward. That silence was to some extent understandable— not least, as Lanzmann suggests, because it was so far beyond previous human experience that no name could properly designate or describe it. But this silence was not only a shroud of amnesia for survivors but also a shield for perpetrators, and thus it had to be broken. In France, Alain Resnais' short, elliptical 1955 film, Night and Fog, was essentially the first public recognition of the Holocaust; and, as Lanzmann noted in his recent wide-ranging discussion with film historian Harlan Jacobson, it took an American historian, Robert Paxton, to fully force the issue on the French.

Lanzmann, himself of immigrant Jewish parentage, was like many of his pre-war generation absorbed in the task of assimilation. The shtetl was behind him, and Judaism wasn't a topic of conversation in the household.

Shocked to encounter anti-Semitism in school, he concealed his identity even while a Jewish classmate of his was beaten almost ritually by fellow students. Lanzmann, who later became a very courageous man, still bears the shame of his own first "silence."

"Assimilation," as he told his audience pithily, "is a destruction." That was certainly the case when the Nazi deportations began.

Killing Germans

Lanzmann recounted his wartime service in the French Resistance, remarking almost laconically that he "killed Germans." He did so as a Frenchman and also as a Communist, he said, but not as a Jew. Even in the midst of war, indeed of the Holocaust itself, his Jewish identity remained a stigma. Asked by a member of the audience whether he had encountered anti-Semitism in the Resistance itself, he responded with a thunderous "No!" whose very intensity suggested, at least to this listener, the possibility of a screened memory.

Lanzmann said he didn't begin to come to terms with his Judaism until he read Jean-Paul Sartre's Anti-Semite and Jew, which provocatively argued that anti-Semites had in effect created the modern "Jew." Lanzmann says this essay was revelatory for him; at the same time, however, it still denied a positive content to Judaism itself. This was, of course, the self-appointed task of Zionism, and then of the State of Israel.

Lanzmann first visited Israel in 1962; he covered its wars as a journalist, and he related how Ariel Sharon— whom, as he said, "I love"— had personally saved his life when he shielded him from an incoming rocket shell.

Truth, 24 times a second

What Israel showed Lanzmann was that a modern Jewish culture could exist, and this discovery sent him back to his own family heritage (which he described in rich and loving detail). From there it was a logical step to address the Holocaust, and thus to conceive the project that would become Shoah.

Lanzmann spent 11 years on the project, a series of interviews with Holocaust survivors and perpetrators, who are filmed head-on by a virtually motionless camera that records their testimony without comment or elaboration. Jean-Luc Godard, who famously said that film was "truth 24 times a second," pioneered this technique with the deadpan monologues offered by his characters, but Lanzmann, operating entirely without irony, adapted the method to a documentary form, and it proved not only suitable to the subject but also in many respects the only possible approach to it.

He had no working title for the film because there was, in his mind, no properly descriptive term for the Holocaust experience. He privately called both the film and its subject "The Thing"— Le Chose. The word "Holocaust" was of course current, but Lanzmann insists that, although the term is now perhaps ineradicable, it's utterly incorrect, connoting as it does a burnt offering in a religious ritual.

Israel's preferred word

The Hebrew word "Shoah" was a little better; it literally means "destruction," but of any sort— human or natural. Lanzmann chose it simply in despair of finding a better one, and was much amused, he says, when it gained international currency and was ultimately adopted as the preferred term in Israel itself.

"Shoah" does not, however, take the definite article as far as Lanzmann is concerned, for that would make it a specific signifier, and the destruction of Europe's Jewry remains for him "L'Innomable— the Unnamable."

Shoah is hardly the only landmark of Lanzmann's long career, which includes six films as well as his now 60-year association with Sartre's Les Temps modernes, which he has edited since 1986. It was indeed to promote his newly published autobiography, The Patagonian Hare, that he had come to share the evening. The book is only belatedly appearing in English after translation into several other languages.

Unrepentant Communist

Lanzmann strenuously objected to the first English version offered him, which among other things replaced his own term "Communist resistance" with "French resistance." This might seem a small bone to pick, but not for a committed leftist who deeply laments the passing of European Communism, whatever its faults.

This was a subject mentioned only in passing during the evening— socialism is, after all, the love that dares not speak its name these days— but for Lanzmann it had a very concrete meaning. During the war, the Western Allies parachuted arms to the Gaullist resistance but, despite the fact that the Soviet Union was in fact bearing the brunt of the fight against Hitler, none to the Communist Maquis in France, who were left to fight almost barehanded.

Perhaps not such a small bone to pick after all.

Of course, silence did greet the Holocaust, not only at the time but also for a generation afterward. That silence was to some extent understandable— not least, as Lanzmann suggests, because it was so far beyond previous human experience that no name could properly designate or describe it. But this silence was not only a shroud of amnesia for survivors but also a shield for perpetrators, and thus it had to be broken. In France, Alain Resnais' short, elliptical 1955 film, Night and Fog, was essentially the first public recognition of the Holocaust; and, as Lanzmann noted in his recent wide-ranging discussion with film historian Harlan Jacobson, it took an American historian, Robert Paxton, to fully force the issue on the French.

Lanzmann, himself of immigrant Jewish parentage, was like many of his pre-war generation absorbed in the task of assimilation. The shtetl was behind him, and Judaism wasn't a topic of conversation in the household.

Shocked to encounter anti-Semitism in school, he concealed his identity even while a Jewish classmate of his was beaten almost ritually by fellow students. Lanzmann, who later became a very courageous man, still bears the shame of his own first "silence."

"Assimilation," as he told his audience pithily, "is a destruction." That was certainly the case when the Nazi deportations began.

Killing Germans

Lanzmann recounted his wartime service in the French Resistance, remarking almost laconically that he "killed Germans." He did so as a Frenchman and also as a Communist, he said, but not as a Jew. Even in the midst of war, indeed of the Holocaust itself, his Jewish identity remained a stigma. Asked by a member of the audience whether he had encountered anti-Semitism in the Resistance itself, he responded with a thunderous "No!" whose very intensity suggested, at least to this listener, the possibility of a screened memory.

Lanzmann said he didn't begin to come to terms with his Judaism until he read Jean-Paul Sartre's Anti-Semite and Jew, which provocatively argued that anti-Semites had in effect created the modern "Jew." Lanzmann says this essay was revelatory for him; at the same time, however, it still denied a positive content to Judaism itself. This was, of course, the self-appointed task of Zionism, and then of the State of Israel.

Lanzmann first visited Israel in 1962; he covered its wars as a journalist, and he related how Ariel Sharon— whom, as he said, "I love"— had personally saved his life when he shielded him from an incoming rocket shell.

Truth, 24 times a second

What Israel showed Lanzmann was that a modern Jewish culture could exist, and this discovery sent him back to his own family heritage (which he described in rich and loving detail). From there it was a logical step to address the Holocaust, and thus to conceive the project that would become Shoah.

Lanzmann spent 11 years on the project, a series of interviews with Holocaust survivors and perpetrators, who are filmed head-on by a virtually motionless camera that records their testimony without comment or elaboration. Jean-Luc Godard, who famously said that film was "truth 24 times a second," pioneered this technique with the deadpan monologues offered by his characters, but Lanzmann, operating entirely without irony, adapted the method to a documentary form, and it proved not only suitable to the subject but also in many respects the only possible approach to it.

He had no working title for the film because there was, in his mind, no properly descriptive term for the Holocaust experience. He privately called both the film and its subject "The Thing"— Le Chose. The word "Holocaust" was of course current, but Lanzmann insists that, although the term is now perhaps ineradicable, it's utterly incorrect, connoting as it does a burnt offering in a religious ritual.

Israel's preferred word

The Hebrew word "Shoah" was a little better; it literally means "destruction," but of any sort— human or natural. Lanzmann chose it simply in despair of finding a better one, and was much amused, he says, when it gained international currency and was ultimately adopted as the preferred term in Israel itself.

"Shoah" does not, however, take the definite article as far as Lanzmann is concerned, for that would make it a specific signifier, and the destruction of Europe's Jewry remains for him "L'Innomable— the Unnamable."

Shoah is hardly the only landmark of Lanzmann's long career, which includes six films as well as his now 60-year association with Sartre's Les Temps modernes, which he has edited since 1986. It was indeed to promote his newly published autobiography, The Patagonian Hare, that he had come to share the evening. The book is only belatedly appearing in English after translation into several other languages.

Unrepentant Communist

Lanzmann strenuously objected to the first English version offered him, which among other things replaced his own term "Communist resistance" with "French resistance." This might seem a small bone to pick, but not for a committed leftist who deeply laments the passing of European Communism, whatever its faults.

This was a subject mentioned only in passing during the evening— socialism is, after all, the love that dares not speak its name these days— but for Lanzmann it had a very concrete meaning. During the war, the Western Allies parachuted arms to the Gaullist resistance but, despite the fact that the Soviet Union was in fact bearing the brunt of the fight against Hitler, none to the Communist Maquis in France, who were left to fight almost barehanded.

Perhaps not such a small bone to pick after all.

What, When, Where

Claude Lanzmann: March 19, 2012 at the Free Library of Philadelphia, 1901 Vine St. ( 215) 567.4341 or www.freelibrary.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller