Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Visiting 1776 in 2017

Celebrating independence at the Museum of the American Revolution

Walking into Philadelphia’s new Museum of the American Revolution, I remained curious and hopeful. I believe that learning history is mainly a matter of studying books. Anything else is inevitably superficial.

A museum can present visuals and artifacts, documents and maps, but can’t instill wide or deep knowledge of the past. I worried it might be taken over by digital gimmickry. But such places often present impressive films that stir the imagination and heart. I was ready for a hodgepodge.

From the spacious faux-marble lobby, I turned into a very big room on the left, for children. A little boy holding a strip of blue cloth asked his father, “Ooh, what’s this?” A beaming fifth grader in a tricorne hat and sharp uniform posed for his dad’s camera.

Filming the revolution

An orientation film turned out to be a beautiful blending of skillfully condensed narrative, a rousing soundtrack, and fine montages of illustrations from paintings, portraits, and other artwork. A digest of the events and meaning of the American Revolution, it was exemplary but didn’t offer much news. For many, it will serve as a good recapitulation of what they already know.

In it, Tom Paine’s Common Sense explains the democratic ideas fuelling the rebellion. Abigail Adams chides John to remember the ladies. Free black people and slaves split loyalties: some joining the rebels, some the British army. Indian tribes also take sides. Loyalists and pacifist Quakers receive a bare mention. As an aside, the most provocative take I ever heard about the War for Independence came from a Quaker librarian whose family had been Friends for 300 years. She said that while Quakers shared some common grievances about Britain, they didn’t think it was worth fighting a war over.

After the fighting ends at Yorktown, we are told, the beginning of the revolution arrives. Over time the revolution’s ideals worked upon the country by ending slavery, including women in the political process, and so on; the revolution continues as a work in progress. The film is up front about prevailing social hierarchies, but sees the ideas underwriting the revolution as major progress. It does, however, omit what happened to all those Indian tribes, and does not fully describe the suffering of African Americans. It presents a success story of “consensus history” in about 20 minutes.

The first Oval Office

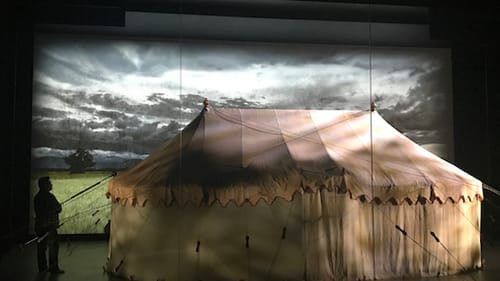

George Washington was a chief reason our revolution worked out better than many. The general lived among his troops, in keeping with the republican spirit, in two special tents, which survive. One is on display here. A brief film tells how he used the white linen oblong tent as “the first Oval Office,” where he wrote letters and dispatches and slept on a hard cot, sharing the tent as living quarters with his enslaved valet William Lee through all the years and rigors of the war.

I finally ventured into the museum’s galleries. This is usually where I get lost in museums, overwhelmed by too much fine print on cards and random objects. There are rifles and powder horns, a British punchbowl and coins, a grandfather clock, little books such as the Pennsylvania State Constitution, regarded as the nation’s most democratic. There is a replica of a Liberty Tree with original wood, under which the colonists gathered for discussions. There was a striking group of figures of Native Americans debating whom to support. I was relieved there were only a few button-pushing affairs, which had something to do with reading small print on the wall and producing posters or newspaper pages to read.

I overheard a young man explaining the sights. He discussed a portrait of Washington, who wore relatively simple clothing instead of wearing fancy military uniforms. However, Washington wore a blue sash as the sign of his authority as commander. Beneath the picture was the authentic blue ribbon, much faded (like that child’s strip of blue cloth). Such expert guidance makes the museum experience come alive, bringing clarity to what can seem like a frustrating maze.

History all around

My visit lasted about two hours, but I missed a great deal, proving the museum map’s motto: “You don’t know the half of it.” There are thousands of artifacts here, but it felt like I only made it through a few dozen.

I still believe history is best learned from books. Edwin Wolf’s Philadelphia, Portrait of an American City: A Bicentennial History provides all sorts of information about life in the city in this period, none of which is available at the museum. Alan Gibson’s Interpreting the Founding: Guide to the Enduring Debates over the Origins and Foundations of the American Republic gives exhaustive scholarly analysis — of the colonists’ ideas, motives, and social classes — of a sort the film only hints at. (Of course, the gift shop does sell books.)

Museums can serve as a spark, a source of wonder and information (even if it’s in bits), a gateway for kids of all ages to further exploration, or simply a pleasant and social way to spend a hot July afternoon. This museum would certainly repay a second visit, and the experience doesn’t end at its front door. When I left, I was greeted with the delightful sight of a horse drawing a tourist carriage through Society Hill.

What, When, Where

Museum of the American Revolution, 101 S. Third Street, Philadelphia. (877) 740-1776 or amrevmuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.