Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The writer who bit his own tail

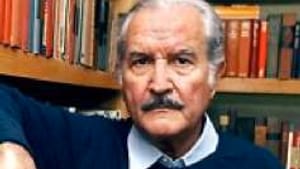

Carlos Fuentes as I remember him

In 1970, one day— more or less like this one— a friend handed me a book that he said I must read. I stuffed it into my briefcase, and when I got home, I found a book in a package in my mailbox, one of the many my very literary uncle in Manhattan regularly sent me. I'm not sure whether I opened the package first or looked my friend's gift, but no matter: They were the same book: One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez.

Not one to ignore strong coincidences, I made dinner, ate, found a chair and began to read….

No, make that: Like Alice, Dante or a time-traveling spirit, I found myself flung into an expansive, sensuous and passionately intelligent new world, rich in spectacular visions, luminous prose. It was an imaginary yet real universe of fantastic stories (a woman so beautiful she was carried away by yellow butterflies) and strange characters (a grandmother who shrank until she was the size of a dinner roll). There were haunted landscapes, uncanny events (an amnesia epidemic that infects an entire town), baroque histories of the Americas, and violent yet plausible politics (bodies disappearing into the sea).

In other words, like many readers of that era, I discovered magical realism, of which Márquez was a leading voice, along with the Argentinean writers Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, the Peruvian Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa, and the Mexican novelist, diplomat and writer, Carlos Fuentes, who died on May 15.

An encounter at Penn

"Many years later…" is how One Hundred Years of Solitude begins; and it was many years later— after becoming immersed in Latin American writing and its versions of magical realism, and finding myself writing about them— that I met Carlos Fuentes while he was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania. He had called me because he liked my review of his latest novel, Terra Nostra.

My recollection is that we talked for hours on different days, had lunch and spent a number of afternoons together"“ including a memorable one with our wives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (He was eager to go there to find out what his friend, the poet Octavio Paz, had seen but not told him about: the work of Marcel Duchamp, of course.) Walking through the museum, Fuentes pointed to a sculpture of a coiled serpent and said, "That is how I write my novels. They wrap around themselves until they bite their own tail."

Afterwards, we had a picnic with quiche and salad and wine on the Schuylkill. It might have been there that he confided, "Borges. No. I don't trust blind men." That comment, as in all of his writing, revealed a bias toward intuition and mystery.

Mexican desert

In the decades since, I have read a good number of his 25 books (in English translations). From the most experimental (Christopher Unborn) to the most probing (Distant Relations) to the most personal (This I Believe: An A to Z of a Life), Fuentes's work is both magical and realistic, magisterial and encyclopedic— a monument to the imagination, a treasure of extraordinary sentences and of the enduring art of the novel. He is probably among the last of his kind.

Some of his books exceeded 600 pages. In them you can find all-encompassing descriptions, like, "He was deep in the Mexican desert, sister to the Sahara and the Gobi, continuation of the Arizona and Yuma deserts, mirror of the belt of sterile splendors girdling the globe as if to remind it that cold sands, burning skies and barren beauty wait patiently and alertly to again overcome the earth from its very womb: the desert."

More often his trenchant explorations of mortality, religion and philosophy intertwined present realities and ancient histories and, always, Mexico. "Do we want now to be Europeans, modern, rich, governed by the spirit of laws and the universal rights of man?" a character asks, in his novel The Campaign. "Well, let me tell you that nothing like that will ever happen unless we carry the corpse of our past with us. What I am asking you is that we not sacrifice anything, son, not the magic of the Indians, not the theology of the Christians, not the reason of our European contemporaries."

Disaster of politics

For Fuentes, the world is extraordinarily rich and, as humans, our responsibility is to affirm, with love and imagination, a way of being in the world together, even though we're prone to maniacal behavior and, most unfortunately, the disastrous desires of others.

By disaster, I mean politics, which was one of the subjects of Destiny and Desire, Fuentes's 2008 novel set in Mexico City. (Fuentes was the Mexican ambassador to France in the 1970s.) The plot, narrated by a severed head, revolves around the plan of a future Mexican president who seeks a mystical/technological formula to sell happiness to a poverty-stricken population. That was Fuentes in a Swiftian mode, though the thousands of drug cartel-related deaths in Mexico today are a reality he knew too well.

In person, Fuentes was real, generous, brilliant and eager to engage his companions. I arranged for lunch with him and Larry Swindell, then the Philadelphia Inquirer's book editor. We met at La Terrace and began talking movies. That is, they, mano Ó mano, were quizzing each other faster than I could drink my first martini.

Movie trivia contest

Larry had written books on Spencer Tracy and John Garfield and had a mind for movie trivia that was as vast as his native Texas. Fuentes, who wrote a book on an affair he had with the actress Jean Seberg, knew American Hollywood film as much as he knew the history of French literature. He had written on the art of memory in his novels.

Within a moment, they were at each other: "Who directed Now, Voyager?" "What other movie beside Frankenstein did James Whale make?" "Who did the music for Lolita?" "Who did the set design for the Magnificent Ambersons?" "And the editor?"

Seriously. These were not the exact questions, but they were as detailed, and asked and answered as rapidly, as the final round of Jeopardy.

The last question, which I do recall exactly, was asked by Fuentes: "Who directed Wuthering Heights?"

Larry was flustered: "Who?"

Fuentes grinned: "I don't know. Nobody knows who directed Wuthering Heights." We all laughed. Appetizers arrived.

Four forces in his life

With his command of languages, histories and worldliness, all of which he tried to weave into the landscapes of his work"“ Terra Nostra is the name of one giant tome— Fuentes was a novelist on the border of nations, living in the midst of a century in transition beyond what his work"“ maybe even literature— could represent. His books are compendiums of pulsating narratives and capacious realms of knowledge. He wrote in a genre that raises questions in a moment when all forms of story are open to suspicions and knowledge is represented as what anyone can locate on Internet sites.

As for History, it was obvious when we talked as well as in his work that it was overwhelmingly a force in his sense of life, along with Truth, Love and Imagination. My capitalization is intentional and not meant to obscure his wise awareness of human weaknesses and the dangerous consequences of unchecked political, social and economic power.

Against those forces, literature and ideas only have the promise of a kind of immortality. Fuentes's name and books work will outlive the deeds of those in power and the accumulations of those with wealth. And they should.

Not one to ignore strong coincidences, I made dinner, ate, found a chair and began to read….

No, make that: Like Alice, Dante or a time-traveling spirit, I found myself flung into an expansive, sensuous and passionately intelligent new world, rich in spectacular visions, luminous prose. It was an imaginary yet real universe of fantastic stories (a woman so beautiful she was carried away by yellow butterflies) and strange characters (a grandmother who shrank until she was the size of a dinner roll). There were haunted landscapes, uncanny events (an amnesia epidemic that infects an entire town), baroque histories of the Americas, and violent yet plausible politics (bodies disappearing into the sea).

In other words, like many readers of that era, I discovered magical realism, of which Márquez was a leading voice, along with the Argentinean writers Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, the Peruvian Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa, and the Mexican novelist, diplomat and writer, Carlos Fuentes, who died on May 15.

An encounter at Penn

"Many years later…" is how One Hundred Years of Solitude begins; and it was many years later— after becoming immersed in Latin American writing and its versions of magical realism, and finding myself writing about them— that I met Carlos Fuentes while he was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania. He had called me because he liked my review of his latest novel, Terra Nostra.

My recollection is that we talked for hours on different days, had lunch and spent a number of afternoons together"“ including a memorable one with our wives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (He was eager to go there to find out what his friend, the poet Octavio Paz, had seen but not told him about: the work of Marcel Duchamp, of course.) Walking through the museum, Fuentes pointed to a sculpture of a coiled serpent and said, "That is how I write my novels. They wrap around themselves until they bite their own tail."

Afterwards, we had a picnic with quiche and salad and wine on the Schuylkill. It might have been there that he confided, "Borges. No. I don't trust blind men." That comment, as in all of his writing, revealed a bias toward intuition and mystery.

Mexican desert

In the decades since, I have read a good number of his 25 books (in English translations). From the most experimental (Christopher Unborn) to the most probing (Distant Relations) to the most personal (This I Believe: An A to Z of a Life), Fuentes's work is both magical and realistic, magisterial and encyclopedic— a monument to the imagination, a treasure of extraordinary sentences and of the enduring art of the novel. He is probably among the last of his kind.

Some of his books exceeded 600 pages. In them you can find all-encompassing descriptions, like, "He was deep in the Mexican desert, sister to the Sahara and the Gobi, continuation of the Arizona and Yuma deserts, mirror of the belt of sterile splendors girdling the globe as if to remind it that cold sands, burning skies and barren beauty wait patiently and alertly to again overcome the earth from its very womb: the desert."

More often his trenchant explorations of mortality, religion and philosophy intertwined present realities and ancient histories and, always, Mexico. "Do we want now to be Europeans, modern, rich, governed by the spirit of laws and the universal rights of man?" a character asks, in his novel The Campaign. "Well, let me tell you that nothing like that will ever happen unless we carry the corpse of our past with us. What I am asking you is that we not sacrifice anything, son, not the magic of the Indians, not the theology of the Christians, not the reason of our European contemporaries."

Disaster of politics

For Fuentes, the world is extraordinarily rich and, as humans, our responsibility is to affirm, with love and imagination, a way of being in the world together, even though we're prone to maniacal behavior and, most unfortunately, the disastrous desires of others.

By disaster, I mean politics, which was one of the subjects of Destiny and Desire, Fuentes's 2008 novel set in Mexico City. (Fuentes was the Mexican ambassador to France in the 1970s.) The plot, narrated by a severed head, revolves around the plan of a future Mexican president who seeks a mystical/technological formula to sell happiness to a poverty-stricken population. That was Fuentes in a Swiftian mode, though the thousands of drug cartel-related deaths in Mexico today are a reality he knew too well.

In person, Fuentes was real, generous, brilliant and eager to engage his companions. I arranged for lunch with him and Larry Swindell, then the Philadelphia Inquirer's book editor. We met at La Terrace and began talking movies. That is, they, mano Ó mano, were quizzing each other faster than I could drink my first martini.

Movie trivia contest

Larry had written books on Spencer Tracy and John Garfield and had a mind for movie trivia that was as vast as his native Texas. Fuentes, who wrote a book on an affair he had with the actress Jean Seberg, knew American Hollywood film as much as he knew the history of French literature. He had written on the art of memory in his novels.

Within a moment, they were at each other: "Who directed Now, Voyager?" "What other movie beside Frankenstein did James Whale make?" "Who did the music for Lolita?" "Who did the set design for the Magnificent Ambersons?" "And the editor?"

Seriously. These were not the exact questions, but they were as detailed, and asked and answered as rapidly, as the final round of Jeopardy.

The last question, which I do recall exactly, was asked by Fuentes: "Who directed Wuthering Heights?"

Larry was flustered: "Who?"

Fuentes grinned: "I don't know. Nobody knows who directed Wuthering Heights." We all laughed. Appetizers arrived.

Four forces in his life

With his command of languages, histories and worldliness, all of which he tried to weave into the landscapes of his work"“ Terra Nostra is the name of one giant tome— Fuentes was a novelist on the border of nations, living in the midst of a century in transition beyond what his work"“ maybe even literature— could represent. His books are compendiums of pulsating narratives and capacious realms of knowledge. He wrote in a genre that raises questions in a moment when all forms of story are open to suspicions and knowledge is represented as what anyone can locate on Internet sites.

As for History, it was obvious when we talked as well as in his work that it was overwhelmingly a force in his sense of life, along with Truth, Love and Imagination. My capitalization is intentional and not meant to obscure his wise awareness of human weaknesses and the dangerous consequences of unchecked political, social and economic power.

Against those forces, literature and ideas only have the promise of a kind of immortality. Fuentes's name and books work will outlive the deeds of those in power and the accumulations of those with wealth. And they should.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

AJ Sabatini

AJ Sabatini